Coiners, Methodists and textile magnates, milltowns, sombre moors and lonely packhorse ways are all encountered in this fine upland walk which visits Stoodley Pike Monument:- lone sentinel of the Upper Calder Valley.

Getting there: The walk starts and ends in Mytholmroyd near Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire. The village can be reached by rail from Leeds,Bradford,Halifax, Rochdale and Manchester.It is also served by buses from Halifax, Rochdale and Burnley. Mytholmroyd stands on the busy A 646 Burnley Road, about a mile east of Hebden Bridge. Car parking is available by the County Bridge, the Burnley Road, and the Mytholmroyd Community Centre.

Distance:8 miles:- a stiff hike!

Map Ref: SE 013 258. OS Outdoor Leisure Sheet 21 South Pennines.

Rating: Walk:*** General Interest ***

There are many routes up Stoodley Pike. Most commonly the ascent is tackled from Mankinholes, or Hebden Bridge. The 'royal road' to Stoodley Pike is undoubtedly from Todmorden, following the 'Fielden Trail' (advt.!)from Gaddings Reservoirs, where from start to finish the Monument will dominate your view. On this route starting from Mytholmroyd however, the Pike is not visible, and indeed will not be in view until we have walked some distance, but this ramble has other compensations as we shall see.

The Mytholmroyd we see today was created by the industrial revolution. Being little more than a river crossing for packhorses near a few outlying farmsteads on the valley floor, the arrival of the turnpike in the 18th century closely followed by the Rochdale Canal, (and eventually the railway) transformed this sleepy little place into a thriving industrial community. Smaller than a town, yet larger than your average village, Mytholmroyd squats on a wide valley floor, not so hemmed in by the hills as nearby Hebden Bridge, its precipice-girt neighbour further up the dale.

Textiles are the tenor of Mytholmroyd's more recent history. Fieldens had a cotton mill here, and the late 19th century saw the blossoming of a thriving blanket making industry. Fustians, corduroys and riding clothes are still made here, and in 1906 a strike in that industry led a local unemployed weaver to build a chicken hatchery in some old orange boxes. By 1906 chick sales had reached 2 million a year, and the business, (Thornber's) became one of the foremost poultry breeders in the world. Mytholmroyd also has a niche in the annals of literature, for on Aspinall Street was born Poet Laureate Ted Hughes, who drew early inspiration from the crags of Mytholmroyd's shadowy brooding Scout, which dominates the southern side of the valley.

The village stands at the junction of two valleys, and also on the boundaries of four ancient townships (Wadsworth, Erringden, Sowerby & Midgley.) Turvin Clough, running down from the moorland fastnesses of Cragg Vale pours into the heavily polluted Calder by County Bridge. This charming little rill is known locally as the Elphin Brook (further upstream it is the Cragg Brook). The same place name element is to be found at nearby Elphaborough Hall, where sheep graze peacefully, happily oblivious to their urban surroundings. Elphaborough translates roughly as 'mound of the elves', and it could be that this place was once an abode of 'the little people', those small, dark and shadowy 'aboriginals' who inhabited Britain even before the Celts, and who almost certainly 'holed up' in remote spots right down into the Middle ages., their strange racial type and alien dialect setting them apart from later waves of people, who came to equate them with 'elves, little people and fairy folk'.

Hollinshed's Chronicle of 1577 gives us our first reference to Mytholmroyd Bridge, describing the Calder as receiving 'one rill near Elphabrught Bridge'. This early bridge was wooden , replacing a ford here dating back to the early Middle Ages. Elphaborough Hall was once the residence of the Steward of the Earl Warren's deerpark of Erringden, and in the 18th century it was the residence of the notorious Isaac Hartley, known as the 'Duke of York' and brother to the even more notorious 'King David' the self appointed leader of the Cragg Vale coiners. The 'Cragg Road' from Mytholmroyd Bridge leads over the moors to Blackstone Edge, with a branch road (Scout Road) to Sowerby on the outskirts of the village, yet neither of these roads were the 'raison d'etre' for the bridge itself. Prior to the arrival of the turnpike age, Mytholmroyd was but an isolated crossing place for a rugged packhorse trod, which, having crossed the river, climbed steeply up Hall Bank and out over the moors to Sowerby, from whence it led to Norland and eventually Huddersfield. All the other roads passing through Mytholmroyd are the product of a later age.

So to the walk! Our route leads out of Mytholmroyd along the Cragg Road, passing Hoo Hole on the right, where, on Thurs 28th June 1770 John Wesley "rode to Mr. Sutcliffe's at Hoo Hole, a lovely valley encompassed with high mountains. I stood on the smooth grass before his house which stands on gently rising ground, and all the people on the slope before me. It was a glorious opportunity. I trust they 'came boldly to the throne' and found grace to help in time of need. At Dauber Bridge, turn right, following a track signed Frost Hole. Following this track up through woodlands ignoring an uphill fork on the right. Beyond a cattle grid where the track bears left to Frost Hole,(which, after years of dereliction is being rebuilt).Continue onwards, following a paved 'causey' through the woodlands of the Broadhead Clough Nature Reserve. The Reserve belongs to the Yorkshire Naturalists Trust and is rich in birch/oak woodlands and associated wildlife. It contains large areas of sphagnum bog. The path ascends steps to the right, then runs to the left below crags, before finally meeting the boundary fence. Here the path ascends steeply to the right, climbing out of Bell Hole onto the shoulder of Erringden Moor. Above Bell Hole stands Bell House Farm, perched on its crag, a lone sentinel over the valleys below.

Bell House was the residence of 'King David' Hartley, and many romantic tales have been told about his gang of homespun criminals who lurked in the wild fastnesses of Cragg Vale in the latter part of the 18th century. More recent accounts tend to play down the romance, depicting the coiners as a bunch of hard, callous and unscrupulous rogues. To me, none of these accounts ring strictly true. Of romance, of course, there was none, such ideas come from the 'Robin Hood' mentality of earlier generations. As for their viciousness and hardness, well the story does contain murder most foul and dark intrigue, but these things were more the consequence of a fateful chain of events rather than the consistently wicked behaviour of totally evil men. The real 'evil genius' of the piece was not 'King David' but an infinitely more unyielding and universal prescence, that of endless, unrelenting and grinding poverty. Poverty was a cruel master. Life was harsh for the Pennine Hillfarmer of the eighteenth century. The cold, wet upland climate did not support much in the way of arable farming, so the hillfarmer had to rely largely on animal husbandry, supplementing his meagre lifestyle with the production and sale of cloth 'pieces'. In 18th century Calderdale almost every building echoed to the 'clack' of the loom and the hillsides were festooned with cloth 'pieces' drying on tenter frames. An old poem gives a good picture:

"Farms with scanty crops and stacks,

handicraft in wool and flax,

Strings of horses carrying packs

coiners haunting woods and slacks

havercake lads and paddy whacks

Such of old was Halifax!"

It was to this remote, poverty stricken landscape that David Hartley returned, some time in the middle of the 18th century, with the intention of putting down roots and practising the new 'trade' which he had picked up whilst apprenticed to an ironworker in Birmingham. He chose his house well. Bell House on its crags is sited like a fortress. Anyone approaching would be spotted long before they arrived, allowing time for any incriminating artefacts to be safely disposed of.

To practice his 'business' in a profitable manner, it was necessary for 'King David' to set up some sort of local organisation, so he called his friends and relatives together, and, in the style of a true "mafioso", made them and offer which they couldn't refuse: A simple way to make easy money (quite literally)! In the eighteenth century, because of a universal shortage of currency, all manner of unusual coins were in circulation. Portuguese Moidores, pieces of eight and spanish "pistoles" for example, were, along with foreign currencies, accepted unconditionally as legal tender. ’oins in those days of course were made of gold and silver, not of base metal as they are today. So what was actually stamped upon the face of the coin tended to be of rather secondary importance. This made life easy for the likes of David Hartley. The idea was brilliantly simple. Having procured a supply of golden guineas the coiners clipped off the edges, filed on new ones and returned the coins to their owners for circulation. The clippings were carefully collected, and then melted down to make bogus moidores. These passed for 27/- each, even though the coiners only put 22/-worth of gold into them. On seven guineas they would make about #1.00 profit, which was a considerable sum in those far off days. The idea quickly caught on with the hard bitten and impoverished local population, who, thrilled by the promise of 'easy money' set to work with a will. In a very short time 'King David' found himself at the centre of an ever expanding criminal empire, which was even to enjoy the collusion of some local worthies and the Halifax Deputy Constable!

The fact that coining was illegal did not seem to occur to these rough hill farmers. Under the Law, diminishing the currency was a 'Misprision of Treason', and as such carried the death penalty. Safely esconced in their remote farmsteads, far beyond the reach of what little law there was, they no doubt felt 'secure' enough to carry on their 'trade' without molestation, and for a while they did just that. Yet they were not hardened criminals. They were poor and it was easy money - It never occured to them that debasing the currency might be to the detriment of everyone, and might even prove a threat to the national economy. When in 1767 the Merchants of Halifax complained to the government about the debased coinage, William Dighton, the local excise man decided to take action. Encouraged by Robert Parker, an energetic Halifax solicitor, Dighton sought to find someone who would inform on the gang, and in August 1769 near Todmorden he found his man. James Broadbent, a 33 year old soldier-turned-charcoal burner who lodged at the house of Martha Eagland of Hall Gate Mytholmroyd, agreed to work for Dighton. Other informers followed.

After an abortive attempt to capture one of the coiners (Thomas Clayton) at Stannery End, the gang were alerted to the danger and £100 was offered to anyone who would dispose of Dighton for them. Shortly afterwards, the arrest of 'King David' in the tap room at the Old Cock in Halifax in Oct 1769, and his subsequent incarceration in York Castle brought matters to a head, and a now determined Isaac Hartley hired two 'hit men':- Robert Thomas of Wadsworth Banks and Matthew Normanton of Stannery End to sort out Dighton once and for all. On the night of 10th November 1769 they repaired to Halifax, where they lay in wait for Dighton outside his house at Bull Green Close (Now Savile Close). As he returned home just after midnight Thomas and Normanton waylaid him and shot him through the head. After kicking his body and rifling his pockets, they left his body in the street to be found by his horrified wife, who had been roused by the disturbance.

By murdering Dighton the coiners had gone too far. The country was appalled by the deed, and as Dighton was laid to rest in Halifax Parish Church, mourned by his wife and eight children, plans were already afoot to deal with the coiners. Lord Weymouth, who was a sort of 18th century 'Home Secretary' wrote to the Marquis of Rockingham about the affair, who, as Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding, decided he would come to Halifax to discuss the matter. Lord Rockingham was a former whig Prime Minister and was destined to lead the government in 1782. He was the patron and friend of the great Edmund Burke and lived on his great estates at Wentworth Woodhouse near Rotherham (See Walk 9). The ringers of the Halifax Parish Church were paid 36/- for the visit of the Marquis, more than the fee for great naval victories. Rockingham must have been a popular man in Halifax. The Marquis made his report and left. He asked that a solicitor from the Mint be appointed to deal with the case, and by the end of 1769 a Mr. William Chamberlayne had come up to Halifax to proceed against the coiners at the government's expense. On 26th Dec 1769 Joseph Hanson, the Deputy Constable of Halifax was charged with clipping, and escaped from custody on Christmas Eve. A price was put on his head. Other arrests followed. A £100 reward had been offered by the government for information leading to the apprehension of Dighton's murderers, followed by a further £100 from the merchants of Halifax. This led Broadbent to incriminate Thomas, Normanton and a man named Folds, who were all sent to York Castle.

At the Spring Assizes of 1770 David Hartley was sentenced to death along with James Oldfield and William Varley, and on the 28th April he was hanged on Knavesmire, his body being brought home for burial in Heptonstall churchyard. The parish registers of St Thomas a Becket Heptonstall, contain the following entry:-

" 1770. May I. David Hartley de Bellhouse in Villa Erringdinensis suspensus in collo prope Eboracum ob nummos publicos illicite cudendos et accidentos. - ie:- David Hartley of Bellhouse was hanged near York for unlawfully stamping and clipping public coin".

24 other coiners (including Thomas and Normanton) who had appeared at the Spring Assizes of 1770 had their trials postponed, and were actually released on bail! At the next Assize, Broadbent's evidence was proven to be untrustworthy. He said he had witnessed the murder of Dighton, but his self contradiction proved he had not! Thomas and Normanton were aquitted, and went home, no doubt congratulating themselves on their close shave! With the execution of 'King David' and the wave of accusations and arrests the coiners were broken. Influential persons who had secretly colluded with the coiners now condemned them openly. Bell House was left alone with its memories. For others, however, the reckoning was yet to come.

Leaving Bell Hole we plod over Erringden Moor, passing boundary stones, before arriving at the start of Dick's Lane by the ruin at Johnny Gap. In the 1840's this unlikely spot was the scene of an annual stock fair held by local farm tenants. Today, Johnny Gap is frequented only by sheep and the occasional walker. Beyond Dick's Lane at a wall, we join the Pennine Way and the western boundary of what once was the Erringden Deer Park. Beyond is Langfield Common, which stretches along the ridge towards Todmorden.

The Pennine Way proceeds to the 'Public Slake Trough' at Stoodley Spring, where, after a refreshing and well earned drink we head up the moor to the 'Pike' itself.

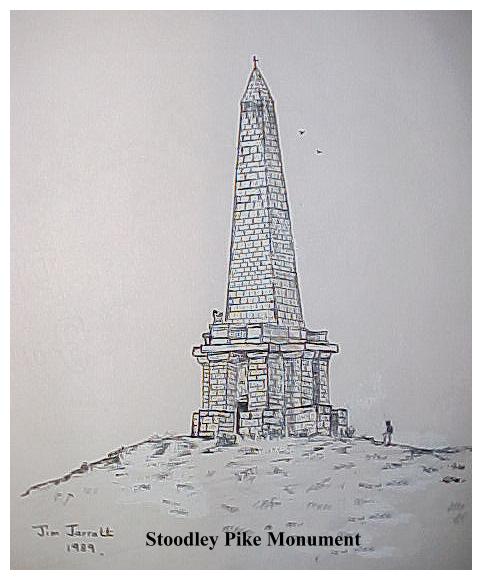

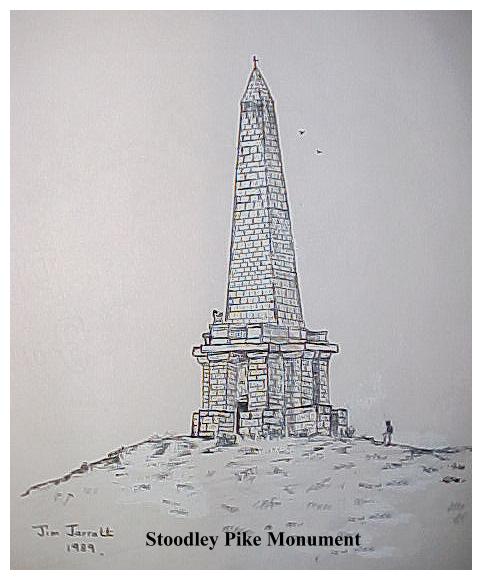

Stoodley Pike Monument is dark, sullen and faintly Egyptian. On a sunny day it is distinguished and grey, but mostly it is moody and black. The wind howls unrelentingly up its winding staircase and whips viciously around its exposed viewing platform. On a winter's day it chills to the bone. Some shelter may be obtained between its great buttresses, but this pallid delight tends to be marred by the annoyingly humanised sheep who mug you for your sandwiches!

The present monument is the third (or possibly fourth) to be erected on this prominent site. The first monument, a cairn of stones, was erected long ago, the last resting place of some ancient chieftain. His bones were reputedly discovered by workmen digging out the foundations for the first Pike in 1814. It has been suggested that the Pike once held a beacon, (certainly one was fired here for the 1988 Armada Celebrations!) At 1,310 ft above sea level, it would have made an ideal site. According to some sources, a building had been erected here before 1814, but whatever this might have been it was almost certainly demolished to make way for The First Pike.

This was erected by public subscription to commemorate the surrender of Paris to the Allies in March 1814. The completed Pike was 37 yds 2 feet 4 inches high. Although constructed on a square base about four yards high, it was predominently a circular structure, with a tapering cone at the top. The monument contained about 156 steps which ran precariously around the inside of the monument, quite innocent of any bannister rail! This was not an ascent for the giddy or faint hearted! After enduring this ordeal the visitor to the Pike might rest in a small room at the top of the pike which contained a fireplace, before plucking up courage for the even more unnerving descent. The career of the first pike was ill-fated and short lived. Then, as now, vandalism took its toll. Steps were removed and the place was generally wrecked. The authorities walled up the entrance up. The final act in the saga took place on the afternoon of Wednesday the 8th February 1854, when the inhabitants of the whole area were unnerved by a rumbling sound resembling an earthquake. A glance at the skyline provided the answer:- the Pike had fallen down!! The collapse was attributed to the structure having been weakened by lightning, which had cracked the walls some years previously. The locals however, were believing none of this. By an unhappy co-incidence the Pike had fallen at the very moment when the Russian Ambassador left London before the declaration of war with Russia. The reason for the fall of the Pike was obvious:- it was an omen! Thus did Stoodley Pike find itself saddled with the myth that its collapse heralds the onset of war!

The Pike did not stay ruined for long. On March 10th 1854, a meeting was held in the Golden Lion in Todmorden with the object of rebuilding it. Various meetings followed, and to cut a long story short, money was raised, an architect (Mr James Green) appointed, and work begun. The new Monument was erected further back from the edge of the hill than its predecessor, to avoid the storm erosion on the face of the moor which had weakened the base of the first Pike. The building contractor was Mr. Lewis Crabtree of Hebden Bridge.

The present Pike can speak for itself. The massive, badly eroded inscription over the door was carved by Mr. Luke Fielden and, surrounded with masonic symbolism, it tells its story as follows:-

Having said our farewells to the Pike, we follow the Pennine Way (and The Fielden Trail) along the ridge to the old Packhorse 'causey' at Withens Gate. Here we turn left,(onto the Calderdale Way) and proceed a short distance to the 'Te Deum ' Stone which hides coyly behind a wall. The face of this ancient stone, faintly reminiscent of a roman altar, is carved with the legend 'Te Deum Laudamus':- "We praise thee O Lord!"

Here people would give thanks for a safe journey over the moors, and coffins would be rested on the stone as they were carried over the 'corpse road' for interment in Heptonstall churchyard. At one time, Heptonstall was the only church in the area, so it was by no means unusual for corpses to be carried over the moors.

Following the Calderdale Way down towards Green Withens Reservoir our route passes through a landscape of derelict farms, shattered intake walls and upland pastures fast returning to moorland and bog. Here, even in summer, it is decidedly wet underfoot. The path descends to a reservoir road which leads unerringly down to the Hinchcliffe Arms at Cragg Vale.

At Cragg Vale we are back in 'Coiner's Country'. In the Hinchcliffe Arms there is a small display of some of the tools of the coiner's trade. The Hinchcliffes were the local millowners hereabouts, and Cragg Vale was once notorious for the child labour in its mills, the 1833 commission describing Cragg Vale as 'the blackest place of all'. The adjacent church of St John-in-the Wilderness was built in 1815 and Jimmy Savile OBE is one of its churchwardens. The early records of this church reveal appalling mortality rates among the children of Cragg Vale. The grasping millmasters hereabouts were it seems, just as greedy as their coining predecessors!

From Cragg Vale we follow the beck for some distance before crossing the Cragg Road and proceeding up through the woods to the outcrops of the 'Robin Hood Rocks'. In the woods here is Spa Laithe, once the venue for an annual 'well dressing' ceremony, and in the 18th century the scene of a dramatic arrest.

As we have mentioned, Dighton's murderers, Thomas and Normanton had been aquitted due to the unreliable testimony of the informer Broadbent. Further information however, was to lead to their re-arrest, this time on charges of highway robbery. On May 4th 1774 Thomas confessed to the murder, but Normanton remained silent. On 6th August 1774 Thomas was hanged on Knavesmire and his body tarred and suspended in chains on Beacon Hill, Halifax. Normanton, (incredibly) was allowed out on bail until the next assizes. Not surprisingly, considering that his friend was by now being eaten by the crows on Beacon Hill, Normanton did not put in an appearance in March 1775, but he sent a plea of guilty. He was sentenced to death in his abscence, and the men sent to arrest him found him here at Spa Laith. There was a chase, and Normanton escaped into the wood, but he was finally caught hiding behind some briars at the bottom of a wall. On April 15th 1775 Normanton confessed on his way to the gallows. On April 17th he joined his accomplice on Beacon Hill. The final act of the coiners tragedy had been played out.

After noting the unfinished millstone still attached to the adjacent outcrop, our route proceeds along the top of the woods and descends Hall Bank Lane. Reaching the edge of Mytholmroyd we pass New House, on the Right (its fine porch is dated 1718). Here lived Thomas Spencer, the brother-in-law of 'King David'. An ex soldier, he escaped the fate of his compatriots, only to be hanged on Beacon Hill in 1783 for leading a corn riot in Halifax!! Spencer's body was afterwards brought home and left on view at Hall Gate. A nineteenth century witness, who saw this as a child, reported that Spencers neck was level with his chin!!

And so, opposite the fine mullions of Mytholmroyd Farm, we reach the end of our journey.A left turn onto the Cragg Road leads back to your car. Forgive me if I turn right onto Scout Road. I'm not being awkward... I'm going home !!!