Crags, canal, nature trails, a seventeenth century mansion, and a 'model village' are all to be found on this semi-urban ramble around the edges of the Calder Valley. At the heart of the walk stands the lofty Wainhouse Tower, one of the best known follies in Britain.

Rating: Folly & general interest *** Walk **

Getting there: From Halifax follow A629 Huddersfield Road. After descending Salterhebble Hill, turn R. for Greetland. Pass over canal and river and continue onwards, passing under railway before road winds R. into West Vale. At traffic lights, turn R., then R. again into the West Vale Car park, which is sited by the entrance to Clay House Park and the North Dean nature trails. Parking is free and there are public conveniences and shops adjacent.

Distance: 6 miles approx.

Map Ref: SE 097 214. OS Outdoor Leisure Sheet 21 S. Pennines or Sheet 104 Leeds & Bradford 1:50 000 series.

Wainhouse Tower is open to the public at certain times of the year. The opening dates are as follows: May Day- 1st May Spring Bank- Sunday & Monday Father's Day (June) Show Day (August) August Bank - Sunday & Monday September Break- Sunday.

Admission 40p . Brochures & postcards available.

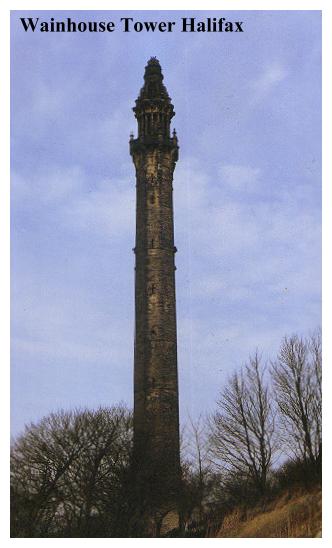

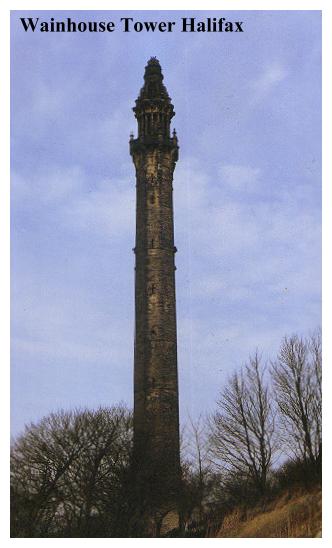

The Upper Calder Valley boasts two fine follies- Stoodley Pike Monument and the Wainhouse Tower. Of these, Wainhouse Tower is the most striking. The Stoodley Pike Monument stands remote and aloof, lost in its moorlands and only really making its presence felt in the landscape around Todmorden. The Wainhouse Tower on the other hand was built at the edge of Skircoat Green, at the limit of Halifax's urban sprawl. It stands on the lip of the Calder Valley, a domineering master to the residents of Sowerby Bridge who, immured in the valley far below seem to scurry about their daily affairs like so many tiny ants! It is difficult not to notice the Wainhouse Tower, yet few people who pass by seem to stop to make a closer inspection. Despite'open days', a 'History Trail', explanatory leaflets in Tourist Information Centres, and improved accessibility, the myths surrounding the Wainhouse Tower still persist and proliferate!

Let me explain what I mean. About two years ago I was travelling home to Mytholmroyd on the train, having spent most of the day in Bradford. In front of me were sitting two rough looking men. They were not together. The dark haired man in the donkey jacket was sitting by the window, whereas the other man, gypsy like, with waistcoat, neck scarf and battered trilby was of that type who sits down next to you on buses and trains and insists (loudly!) on making conversation without consideration of the fact that you might simply want to snooze or read your newspaper in peace. You know the type- the self appointed expert on everything who refers to you as 'pal' and never allows you to say anything except 'yes', 'no', 'Hmmm' and 'well...'!!

We had pulled out of Halifax station, and 'Mr. Gyppo' was still in full throat. As we crossed the viaduct by Copley the Wainhouse Tower came into view. Mr. Donkey Jacket, whose conversation thus far had not really progressed beyond 'yus' and 'erm' suddenly became more animated:-

"Well whats that then up theer? I've allus wondered abaht yon tower; I once heard tell that it were...." "That's t'Tower o' Spite pal. You've not heard o't' Tower o' Spite?? It were this feller, Lord Halifax, built it to spoil his neighbour's view. It seems him an' his neighbour fell aht ovver a woman, an t' lass killed herself by jumpin' off o' t'tower. Tower o' spite that pal.... Tower o' spite.

I cannot recall the conversation that followed. Suffice it to say that it was the most fanciful fabrication I had ever heard, and by the time I got off the train at Mytholmroyd, I was heartily regretting that I could not continue on to Todmorden, as I would have loved to have listened in on the cock and bull story he no doubt must have concocted to explain away the prescence of Stoodley Pike. However, this little incident graphically demonstrates the myths that cling to the Wainhouse Tower in particular and to follies in general.

It is curious that this gentleman mentioned someone jumping off the tower. A Canadian Newspaper, 'The Sun', recently ran a picture of the Wainhouse Tower with the headline 'TOWER OF DEATH'. According to this account the tower was built in Budapest in 1504 as a memorial to a victorious general! The story goes that a merchant, eager to marry the 'other woman' lured his wife to the top, and pushed her over the balustrade. The merchant was brought to trial and sentenced to the same death as his victim. From then on the tower became the regular venue for executions, and thousands of malefactors ascended the tower's 400 steps to be thrown to their deaths on the rocks below! Surely not even my 'pal' would have swallowed that one! Half of Canada though, apparently did. The story only appeared locally when the picture of the tower was noticed by a Mrs. Sylvia Ward, who had emigrated to Canada from Halifax in 1974. She brought the article back home, and the local press had a good laugh at it. Still, it makes you wonder about what you read in the papers!

Our journey to the Wainhouse Tower begins at Clay House Park.Clay House is a striking 17th century house with an old barn, and it is no surprise to learn that it was once the homestead of the Clay Family. In 1957 there was some speculation that this might have been the site of the long lost Roman Cambodunum when a Roman altar (dating from AD 208) was found hereabouts. It was dedicated to the local goddess Victoria Brigantia, and is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. A replica remains.

Clay House has a visitor centre and is also the starting point of the fifty mile long Calderdale Way which was opened in October 1978 - a challenging expedition if you can spare the time!

Our walk leads into North Dean Woods where there are nature trails. The woodland is predominently oak and birch, especially the latter, which once clothed the whole valley long ago. In the 18th century the North Dean Wood Charity eased the lot of the local poor with profits derived from the sale of the wood's timber. Further along the hillside there is much evidence of quarrying. Quarrying is a venerable industry hereabouts, although happily it no longer scars the landscape in the way it once did. Many quarries have disappeared under landfill, and the few that still operate (around the Shibden Valley for example) are carefully regulated. Here above the Calder, the stone has been quarried from the outcrops on the valley edges and has left indelible scars. The local millstone grit (known as the Elland Flags) is very resistant to sea erosion, and consequently has been exported for use in harbours all over the world. In Calcutta, Hong Kong, Sydney and Copenhagen you will find Halifax stone, as you will in the War Office and the British Museum. If ever we find a city on Mars you can bet your boots that its streets will be paved with Elland flags! It is also thanks to the local revolution in quarrying (which began in the early 17th century) that there are so many fine stone houses in the area dating from this period. These 'Halifax houses' with their fine mullioned and transomed windows, with gables topped by ball finials must surely represent an architectural style that is unique to this area. If you look at Thomas Jefferys map of the district, which was drawn in 1775, you see the Calderdale hillsides thickly packed with these farmsteads, whereas Bradford is little more than a village, and smaller than Halifax! The reason is that prior to the Industrial Revolution Halifax lay at the centre of an enormous domestic based textile industry, so typified by those tenter frames decked out with cloth 'pieces' which Defoe so vividly described on his journey over the 'mountains' to 'Hallifax' in the eighteenth century. All these farms were busily engaged in spinning and weaving, and in taking their finished cloth to Halifax Market. It is ironic that when Halifax opened its new custom built 'Piece Hall' in 1779 this old established way of life was already standing on the brink of its own extinction! Machines, mills, canals and railways were to create new towns where formerly there were villages, and the upland farmsteads would be left to fall into decay as the population progressively moved downhill to where the work was. This pattern has remained right down to the eighties, and only now, with the arrival of affluent 'yuppy' outsiders are the hills starting to be repopulated. Tourists throng around Walkley's Clog Factory at Hebden Bridge. 'Peg rugs' sell in trendy 'craft shops' for astronomical sums (In the 50's my mum used to make them because we couldn't afford a 'proper' rug!). The rough stoneware pottery, which our parents threw out in favour of Staffordshire china is today the tableware of the affluent and mill bobbins make upmarket tourist souvenirs. It is ironic that the symbols of former poverty should today be equated with middle class trendiness. To my parents and grandparents all these things were,(and still are) junk:- mute symbols of the poverty and the hardships they had to endure in the mills, quarries, mines and back-to-back slums of the black industrial West Riding.

As we walk along the hillsides around Norland the slumbering memories of this upland landscape are neatly dovetailed with all the evidences of urban development in the valley below. Those evidences are everywhere. Copley, like a small version of Bradford's Saltaire, was a custom built community centred on its mill. The canal runs alongside the river, and the magnificent (or repulsive- depending how you look at it!) 23 arch Copley Railway Viaduct tells of the coming of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway in 1852. The pattern continues down to the present day. The latest 'beautification' to grace this section of the Calder valley is the New Halifax Building Society Computer Centre which was completed in 1989. This drab building has but one saving grace- the fine drystone walling around it was built by Ray Howarth, a shepherd, who when not grazing his sheep on Oldtown Cricket Pitch near Hebden Bridge, builds walls and breeds budgies. Ray was brought up on a hill farm tucked beneath Erringden Moor. Like so many embattled locals he lives in a council house at Oldtown, surrounded by 'offcomers'! His walls will stand when the 'Halifax's' computers have rusted into so much electronic junk. The walls belong to the Pennine landscape, their stones spring from it in an elemental way. The nineteenth century builders of mills and chapels knew this, which was why they built in ashlar and millstone grit.. It seems to me that todays architects, armed with methods and materials that have not yet withstood the test of time are fated to learn the lessons of our forefathers the hard way!

Sowerby Bridge is a product of the Industrial Revolution. It was originally just a river crossing, the hub of 'civilisation' being the village of Sowerby, on the adjacent hillside. The Industrial Revolution changed all that and Sowerby Bridge grew into a mill town, leaving Sowerby as an outlying satellite.

Despite the later impact of the railway, Sowerby Bridge's real history began with the arrival of the canal. Its canal basin marks the limit of the Calder and Hebble Navigation and the start of the transpennine Rochdale Canal. The Calder and Hebble was surveyed by John Smeaton in 1757 and opened to Sowerby Bridge Wharf in 1770. Smeaton was of course the builder of the first Eddystone Lighthouse, and in 1756, when first approached by the local canal promoters, he had been at Plymouth engaged upon that project. The Rochdale Canal reached the Sowerby Bridge basin in 1798. With the arrival of the railways Sowerby Bridge gradually turned its back on the canal, and, although in commercial use right down to the 1940's the waterways were gradually allowed to fall into decay, the Rochdale in particular becoming a repository for all the rubbish of the neighbourhood. Happily, the Calder & Hebble was spared the worst excesses of the decline. Where the commercial traffic left off the tourist traffic took over, and The Sowerby Bridge Basin was gradually developed into the fine marina it is today. The Rochdale was less fortunate - its locks were capped with concrete and sections of it were filled in and culverted. The rubbish and the weed did the rest. Throughout the 'eighties however, the Rochdale had been undergoing restoration and with the construction of the new 'Tunnel under Tuel' Lane, followed a few years later by restoration at the Rochdale end and a passage under the M62 motorway the canal is now navigable for all of its length and has been reconnected into the national network.

Today Sowerby Bridge is very much a community in decline. This is sad for a town which once boasted that if it could be bought, somebody in Sowerby Bridge was manufacturing it!! We can only hope that better times lie ahead.

We ascend the hillside to the Wainhouse Tower. After the rural delights of the Norland side of the valley, the landscape hereabouts is suburban to say the least, and if a visit to the Wainhouse Terrace is contemplated the busy A58 road will need to be negotiated. The Wainhouse Tower is 253 feet high and contains over 400 steps. It is estimated to contain over 9000 tons of material. The view from the top is phenomenal, as is the change of climate. I once went up the tower in a tee shirt on a warm summers day when people were sunbathing on the grass below, only to find myself chilled by an icy biting wind which was howling around the observation platform. Ascending the tower is an interesting (and tiring!)experience, but you are unlikely to get a chance to do so unless you arrive here on a bank holiday weekend, when the tower is opened to the public.

Now for the true story of the Wainhouse Tower, which is also known as the Octagon Tower, Wainhouse Folly, the Observatory and J.E.W.'s Folly. John Edward Wainhouse was born in 1817 and worked in his uncle's dyeworks at Washer Lane. On the death of his uncle in 1856, Wainhouse inherited the dyeworks together with various other properties. It is not known whether or not he personally ran the dyeworks but in 1870 he leased the premises to one Henry Mossman. Now Wainhouse's wealthy neighbour was Sir Henry Edwards, who resided at nearby Pye Nest, and it is said that Wainhouse constructed the tower out of spite against this man, with whom he had an ongoing feud. This is not strictly true, but the legend is not entirely without foundation as we shall see.

The fact is that the Wainhouse Tower is actually a chimney. There was no real mystery attached to it, it was simply built to serve the Washer Lane dyeworks as part of an early attempt to combat atmospheric pollution! In those days Halifax was a black industrial town frequently blanketed with smog for days on end (Even in the 1950's Halifax was a black, grimy town!). It might seem surprising therefore, to think that there was concern about atmospheric pollution in the dark days of the 19th century, but concern there indeed was, and Smoke Abatement Acts had already been passed by Parliament. This is where Edwards first comes into the picture. He complained to the authorities about the smoke from the Washer Lane Dyeworks, and it was in response to this that Wainhouse set about building his 'chimney'. If there was a feud between Wainhouse and Edwards, this was no doubt the point at which it began.

John Edward Wainhouse set out to build a chimney which would stand well above the smoke nuisance level, some 350 metres or so up the hillside from the dyeworks, connected to it by an underground flue. He employed a local architect, Isaac Booth (who was also Edward's architect!), to build for him a chimney which would do the job without appearing ugly (A bit odd considering that there were plenty of ugly chimneys around at the time!). Booth designed a conventional circular chimney with an octagonal stone casing and a spiral staircase running between the two. He planned to cap the whole thing with a pedimented balcony. Why there needed to be a staircase is a total mystery. It could have served no useful purpose, especially if smoke was belching out of the chimney. Even at the planning stage the structure was in danger of becoming a folly.

Building of the tower began in 1871. Stone was hauled up the inside of the chimney by a tripod set up on top of the structure. One of the blocks of stone which held the winch can still be seen near the tower entrance. At one point the tripod collapsed and a large stone fell onto the foremans son, Isaac Buckley, who lost an arm as a result. In 1873 there was a change of tack. Sir Henry Edwards, who was known to be boastful man, bragged that from no house on the hills around his Pye Nest estates could anybody get a view of his private gardens. It seems that Wainhouse planned to alter this state of affairs by building an observatory on the top of his chimney! Wainhouse had to employ a new architect. Booth was getting fed up with the feud and could no longer brook being the servant of two warring masters. He was caught in the crossfire and had had enough. In his stead Wainhouse appointed his assistant, Richard Swarbrick Dugdale, who completely redesigned the upper section of the tower. He created a two tier structure with large lower and smaller upper balustraded balconies. The whole thing was surmounted with a lantern dome and finial.

The building was finally completed in Sept 1875. It was fated never to be used as a chimney. Even before its completion this had become obvious, as Wainhouse had finally sold the dyeworks to Mossman, and the tower was not included in the deal! The struggle over the smoke from Washer Lane Dyeworks continued unabated, but Wainhouse's Tower no longer had any role in the proceedings. It had already transcended the status of 'mere chimney'.

John Edward Wainhouse died in 1883. Since then his tower has had mixed fortunes. In 1893 it revealed its true nature when it was leased to Joe Brook Carrier at a rent of £15 per annum. He employed it for its only useful purpose, simply opening it to the public and charging a small fee to ascend the tower! By 1893 there was talk of demolishing it but mercifully this did not happen. At the turn of the century the entrance to the tower was used as a hen hut, and in 1909 a Mr. P Denison was using it as an aerial for radio transmissions. In 1912 it was suggested that the tower be used as a crematorium, an idea no doubt inspired by the adjacent graveyard, but thankfully this came to nothing. In World War Two the tower was used as an ARP observation post, and in 1963 it aquired a white CND sign, which has since been painted out. On royal occasions the top of the tower is sometimes illuminated, the last time this happened being in 1977 for the Queen's Silver Jubilee.

I need hardly mention that the view from the top of the tower is excellent, and Stoodley Pike, The Jubilee Tower, The Whitley Moor Gazebo and the Emley Moor Transmitter are all visible from the viewing balcony.

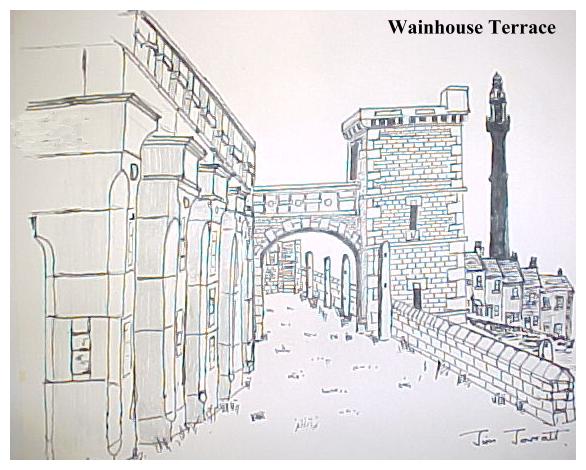

The tower is not Wainhouse's only monument. His house, 'West Air', is now the 'Royal Hotel', (recently renamed 'The Folly') and the Wainhouse Terrace Colonnade stands beside the A646 Burnley Road, being, despite the hazards of the A58, well worth the necessary detour. The colonnade was stone cleaned in 1973. Across the road stands another curiosity- a mullioned and transomed 17th century frontage now incorporated into a retaining wall. This stands beneath the modern New Allan Fold Inn. We must assume that this is all that remains of the 'Old Allan Fold'.

From here back to North Dean the route is predominantly built up, but not without odd bits of crag, woodland and open space. Nearby is Savile Park, which is Halifax's answer to Harrogate's 'Stray', and which is the setting for the odd circus and Halifax's annual show. In days gone by, when it was Skircoat Green it was a venue for Chartist meetings. It is said that the Chartists smuggled pamphlets into Halifax in a coffin and met at the Standard of Freedom Inn not far distant. The Green was given to the town in 1866 by Captain Savile who sold his manorial rights for the sum of £100 on condition that the council would do something about smoke abatement in the area!.

Savile Park ends in the clifftop Albert Promenade overlooking the Calder Valley. Here there are crags and trees,and a potential playground for the rock climber. We make our way to the canal and ultimately to Copley, which was built between 1847 and 1853 by Colonel Edward Akroyd, who was a worsted manufacturer and founder of the Yorkshire Penny Bank. Copley was a model village, preceding Akroyd's other 'model community' of Akroyden, which he sited near his house at Bankfield (Now the Halifax Museum). It also predates Sir Titus Salt's model community at Saltaire, and this alone makes it historically important. At Copley Akroyd had a canteen shed where 600 workmen could be served dinners of meat and potatoes at 2d a throw. The mill was built in 1847 with an 1865 addition, but has since been demolished. Copley had its own school (1849), library (1850), and of course the church, a fine neo gothic structure, dedicated to St. Stephen, which stands across the river and was built 1863-5. The architect was WH Crossland.

Beyond Copley we once again enter North Dean Woods, and make our way back to Clay House. Personally speaking, I do not find this part of Calderdale as attractive as the landscapes further up the valley beyond Luddendenfoot. To me the area is marred by the sewage works, trunk roads and general industrialisation . Nevertheless, it is still well worth a visit, and despite first impressions you will find an interesting, stimulating and generally enjoyable ramble. You will also encounter what must be the finest folly in Northern England. Even if there were nothing else of interest, this alone would make the walk worth undertaking, but there is interest, and lots of it, all you have to do is seek it out!

2007 STATUS REPORT! THE FOLLIES IN THIS WALK ARE UNDER THREAT!

In an age where we are starting to see the value of rogue architecture, and funding is becoming available for folly restoration, Calderdale Council has closed the Wainhouse Tower and is considering demolition of the Wainhouse Terrace, which they have allowed to get into a very sorry state. As usual the culprit is local government health and safety paranoia! We are informed that Wainhouse Tower is currently unsafe, yet the Landmark Trust have inspected it and found it to be structurally sound apart from some loose masonry on the viewing balcony. Surely money is available to fix this and ensure future public access to this remarkable monument. When you close a prospect tower you drive the first nail into its coffin. So (as they keep saying in the local rag), 'come on Calderdale!' lets have Mr. Wainhouse's follies back!