11. SORRELSYKES PARK & THE AYSGARTH ROCKET

A pretty Dales village, a waterfall, a ruined church and an odd concentration of highly individual follies characterise this fine promenade along the limestone terraces of Wensleydale, not far from the famous Aysgarth Falls.

Getting there: Leave A1 at Leeming Bar and follow A684 to Leyburn. (Alternatively A6108 to Leyburn from Ripon, via Masham.) Continue along A684 towards Aysgarth. Just beyond Swinithwaite turn L onto B6160 to West Burton. Note: West Burton may also be approached from Langstrothdale via Kettlewell and Buckden (B6160), or from Ingleton via Ribblehead, Hawes and Bainbridge (B6255-A684):- both highly scenic routes.

Distance: 4 m. Easy. Kids will enjoy it, but take care on the busy A684.

Map Ref.: SE 017 866 OS Wensleydale & Wharfedale Sheet 98. 1:50 000

Rating: Walk:- *** Follies & General Interest:- ***

"Before you know a stranger you must summer him

and winter him and summer him again"

Old Yorkshire Saying.

Limestone at last! Waterfalls, ravines, clints, grykes, and caves characterise the distinctive landscape of the Yorkshire Dales National Park. The valley of the Ure was carved out by glaciers, and when they receded they left behind the beginnings of today's unique landscape. The white scars and velvet turf of the limestone terraces are a walker's paradise, which, with ascent give way to heathery moors and gritstone outcrops. The predominently rural nature of the Dales has also left a rich historical legacy. Lynchets, prehistoric hut circles and ancient earthworks abound, undisturbed by the passage of centuries. The Yoredale Series limestone around Wensleydale is scarred and honeycombed with the remains of intensive lead mining activity. Today the mines are derelict and the tough hard bitten miners who once worked them not even a memory.

This is 'Herriot Country', but you will search in vain for those poverty stricken hill farmers who comprised the bulk of his customers. Since the war the history of the Dales has been one of steady depopulation. Poverty, unemployment, (and more recently the soaring prices of property) have forced the genuine dalesman to leave his birthright and to live in the towns to the north and south. He has been supplanted by the TV Producer, the yuppie accountant and the 'off comed 'un' who will pay a kings ransom for a converted barn or a weekend cottage in a Dales village. Consequently the only 'true born' dalesfolk who remain are those who were always well heeled, or old folk who had homes here before the Dales became fashionable with the 'nouveau riche'. On a summer weekend you will find the villages of the Dales jammed up with walkers, climbers, cavers and tourists, but come here on a January Wednesday and you will find ghost towns filled with affluent, trendily modernised and quite empty properties. The 'weekend cottage syndrome' has taken over!

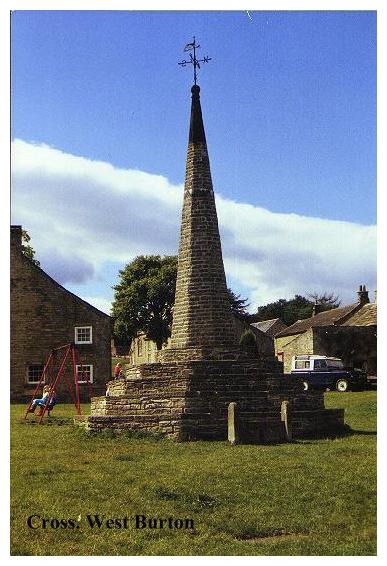

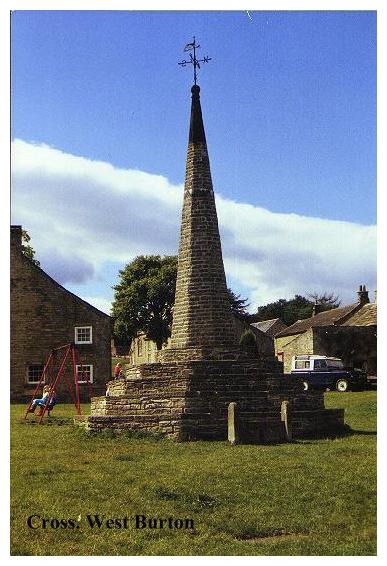

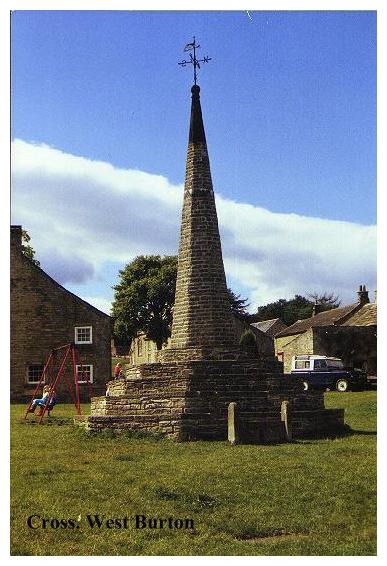

West Burton slumbers peacefully around its greens, tucked away in the folds of Yoredales' shattered landscape. Geographically it suffers from an identity crisis. Standing near the meeting of Bishopdale and Waldendale not far from the point where both of these tributaries join the the Ure in Wensleydale, it is perhaps more to be associated with the two former than the latter. The confusion is by no means new. The village in past times has been variously known as Burton-in-Bishopdale and Burton-cum-Walden. West Burton was once an industrial community of hand knitters, dyers and woolcombers. Today it exhibits the imported affluence typical of all dales villages. Central to West Burton is its magnificent village cross, like a miniature church spire standing on a flight of steps. The cross was erected in 1820 and restored in 1889.

The village stocks stand adjacent. Though obviously not the original ones they have nevertheless an interesting record of use. In the 17th century Quakerism spread throughout the Dales, and was not always well received. In 1660 Samuel Watson of Stainforth Hall in Ribblesdale came to West Burton with the intention of holding a 'Friends' meeting. Unfortunately- "One wicked fellow with a great staff and pistol" threatened to shoot him, and beat him unconscious with his staff. Poor Watson was revived, put in the stocks for a while and eventually thrown in the river. So much for Dales hospitality!

Our walk starts by the West Burton Methodist Chapel. Follow the road through the village, passing swings, the village cross and stocks. To the east of the village where the road winds to the left, turn right, following signed route 'To Waterfall', passing the old mill to a footbridge over the beck just downstream of West Burton's fine cataract, a place for a picnic or a paddle! From the footbridge our route proceeds via Barrack Wood to Morpeth (or Morphet) Gate. This is an old drove road; the word 'Gate' has not the modern meaning but is derived from the Norse 'Gata' meaning 'road', or 'way'. This was originally the main highway up Wensleydale from Middleham, passing over West Witton Moor beneath the flanks of Penhill Beacon. Once this remote trackway was alive with traffic heading for Yoredale's markets and fairs, today it is frequented only by its memories and the occasional party of hikers.

At Morpeth Gate turn right, following the lane uphill until a sign (to Templar's Chapel) appears on the left. From here a straightforward route leads around the hillside along a grassy limestone terrace, from which there are fine views to Castle Bolton and Addleborough. Soon we reach a stile in a wall entering a lane, on the far side of which lies the fenced ruins of the Penhill Preceptory.

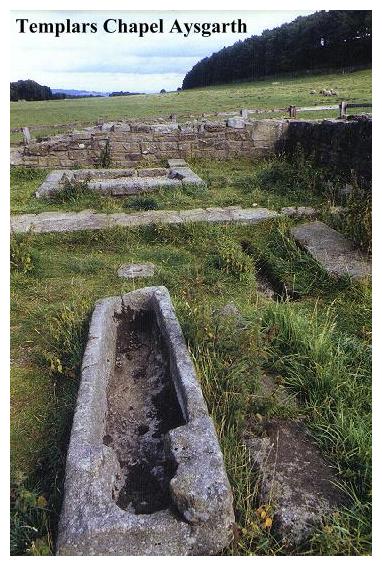

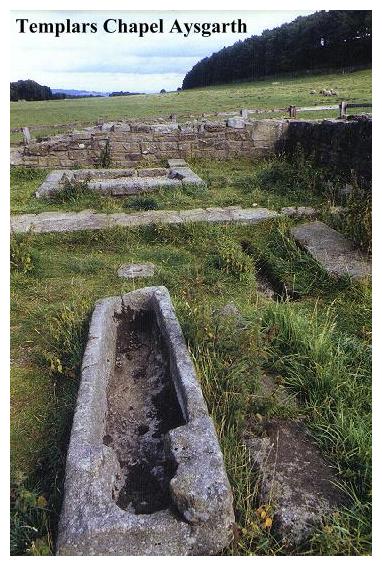

The notice reveals all and nothing."Penhill Preceptory- These walls and graves belong to a chapel in a preceptory of the Knights Templars, built in c.1200 and handed over, on their suppression in 1312 to the Hospitallers. The chapel, the remains of which were uncovered in 1840, served adjoining residential buildings that have not been exposed."

The Templars, along with their arch rivals the Hospitallers, or Knights of St. John, were religious orders of knights of great military prowess who had taken priestly vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. The origins of these military orders of soldier/monks lay in Outremer,'The Land beyond the Sea', which was the mediaeval name for the Holy Land at the time of the Crusades. According to the Frankish historian Guillaume De Tyre, the Order of the Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon was founded in 1118 by one Hugues De Payen, a vassal of the Count of Champagne. According to legend, De Payen, with 8 comrades at his side, presented himself to King Baudoin I of Jerusalem (whose elder brother Godfroi De Bouillon had captured the Holy City 19 years previously). The declared purpose of the Templars was to protect the highways leading to Jerusalem in order to ensure the safety of pilgrims en-route to the Holy Sepulchre. Baudoin was so pleased with this noble objective that he placed a wing of the royal palace at their disposal. According to tradition, their quarters were built on the site of the ancient Temple of Solomon, and it was from this that the order was to derive its name.

From such humble beginnings the order grew to fame and fortune, and by the middle of the 12th century they had established bases all over Europe. In 1128 their Constitution was drawn up by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, and with such powerful support their influence and numbers grew accordingly. Scott's 'Ivanhoe' gives us a good description of a Templar. Haughty and arrogant he wore (as his Rule dictated) a long beard and a mantle of white linen with a distinctive red cross. Often Templars might be seen as advisors to princes and kings.

With the fall of Jerusalem to the Saracens the Templars set up their headquarters first in Cyprus and then in France. Under papal authority they enjoyed exemption from taxes, tithes and interdict, becoming as a result increasingly powerful, wealthy and arrogant. From their traditional stamping grounds in Palestine their sphere of influence became increasingly the political arena of mediaeval Europe.

The Templars were essentially a secret society. Ruled over by a Grand Master, their rites and inner mysteries were known only to initiates of the brotherhood. Unfortunately this deliberate veil of secrecy created not only a tightly knit brotherhood but also a fertile seeding ground for the accusations of their enemies. In 1307, supported by Pope Clement IV, Philip the Fair of France (who had long cast covetous eyes on the Templars' vast assets) accused the Templarsof heresy and witchcraft. Arrests were made and 'confessions' extracted by torture.The Templars were said to have worshipped a Devil called Baphomet, a bearded head, which had given them occult powers. There were charges of homosexuality and obscene rites. The outcome was never in doubt; between 1307 and 1314 hundreds of Templars were burnt at the stake, their assets confiscated and the Order scattered. In March 1314, the Order's Grand Master, Jacques De Molay, was roasted to death over a slow fire. The Templars had passed into the obscurity of history.

In England the Templars fared better. Philip's own son-in-law, Edward II of England at first rallied to the Order's defence, but was eventually persuaded to suppress them. In the scramble to get hold of their assets some Templars were arrested, and it is reported that John De Bellerby, Master of the Penhill Preceptory was imprisoned with others in York Castle in 1309. The majority however, were simply ejected from their preceptories, which were handed over to the Hospitallers and we must assume that their ultimate fate was considerably less unpleasant than that of their European brethren.

The Penhill preceptory was excavated by Mr. Anderson of Swinthwaite Hall, who found spurs and fragments of armour. Prior to this it had been just a mysterious mound. Preceptory churches are unusual in that they were circular in plan. The Penhill Preceptory is even more unusual in that it is not. The outline is of a rectangular building with a door at one end and a small chancel at the other. In front of the chancel lie three stone coffins the size of which makes us marvel at the smallness of our mediaeval ancestors. It must have been a tight fit for a dead knight!!

After inspecting the Templars chapel, retrace your steps to the lane and then turn right, following it down to the road by Temple Farm, which reputely stands on the site of the Preceptory's secular buildings, and opposite, where our path joins the main road, we encounter the first folly on our walk.

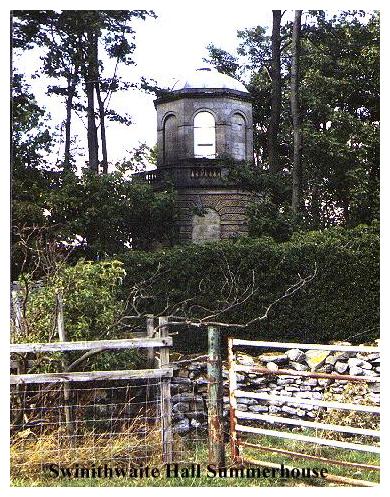

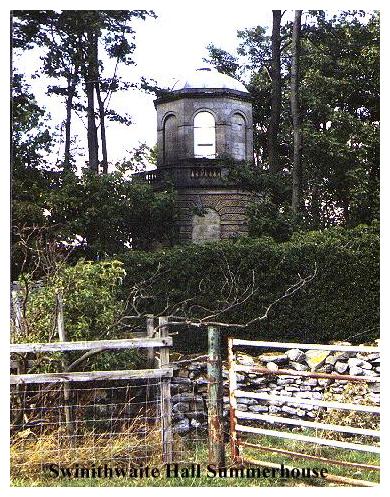

Surrounded by a high wall amidst an overgrown garden, a dilapidated summer house stands on a small knoll. This Summer House belonged to Swinithwaite Hall, a mile down the road, being built in 1792 for Mr. T.J. Anderson. The Architect was John Foss, of Richmond. The building (for those intrepid enough to get close to it) has an octagonal base with a fine bas relief of a pointer above the door. Inside a staircase leads to a domed octagonal chamber, which apparently still possesses most of its fine plasterwork. A balcony runs around the outside. Lonely and neglected, the traffic to Aysgarth rumbles by and the building stands forlorn.

Turn left, and follow the main road (A684) downhill to its junction with Ellers Lane (B6160). Turn left down this road, (with follies now in view on L.). After passing a small lodge, a stile at Edgley gives access to an indistinct path which leads diagonally across the pasture to join a track from the lodge, immediately beneath the Sorrelsykes Follies. (Which, although not on the right-of-way may be inspected without difficulty.)

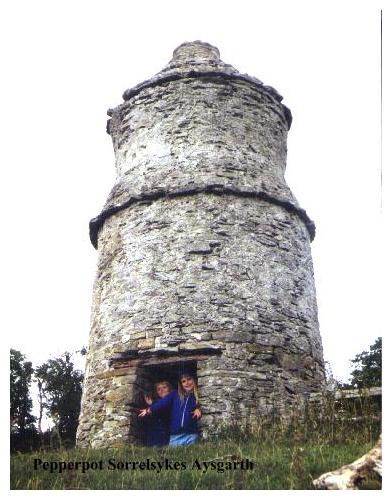

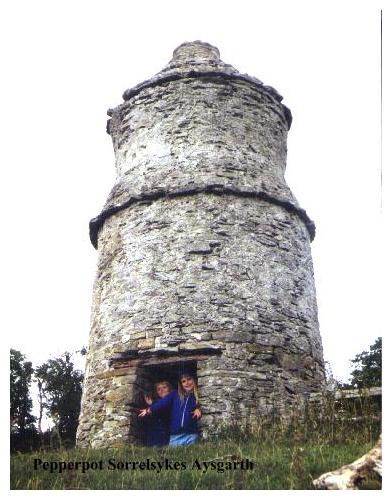

The Sorrelsykes Follies can't be missed. Standing on the edge of a steep slope to the left of the path they are easily (if unofficially) accessible. The Sorrelsykes Follies were to all intents and purposes built as eyecatchers for Sorrelsykes Farm opposite, which, (on this side at least) displays the frontage of an 18th century palladian mansion. There are three follies standing in a neat row on the edge of the limestone terrace, in company with a typical dales barn. The first and largest, known locally as the 'Rocket Ship' is essentially a cone rising from a square base with a small room inside. The folly is built of local limestone, in a style which suggests that its anonymous builder was more used to constructing lead mine adits than than fanciful follies. In true lead miner fashion it seems he decided that the cone might become unsafe, and so 'propped' it with a series of buttresses. As a result the whole thing looks like something out of a Dan Dare cartoon. It was constructed around 1860.The second folly is less impressive, being little more than a small gateway constructed from two cones with an arch in between. Finally we come to the Pepper Pot. With a large smoke hole, this odd, spinning top like structure was reputedly built around 1921, and was used for the curing of bacon!

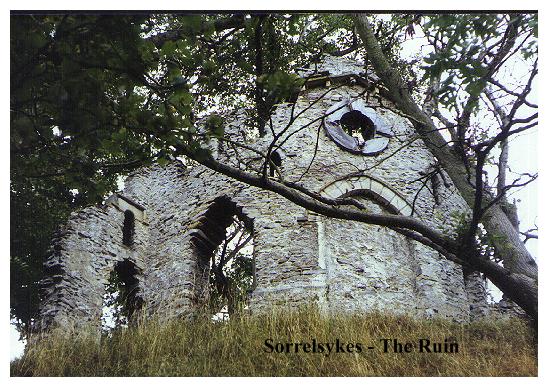

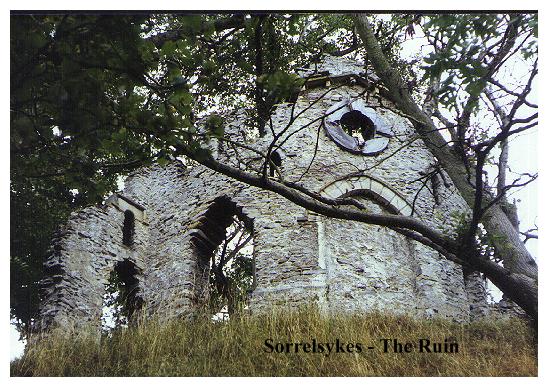

The final folly in the Sorrelsykes Group is a Sham Ruin. This lies beyond the barn, just below the edge of the next limestone terrace. Standing above a steep rocky scree and half hidden by the trees, this eyecatcher was apparently built to obscure the remains of 18th century lead workings. Traces of the mine may still be seen where an old gully leads down to the last vestiges of the spoil heaps. The main part of the ruin consists of a blank arch, an oeil-de-boeuf window and a small classical pediment. One suspects that today it is more ruinous than when it was first constructed.

And so our walk proceeds by quaint barns back to Morpeth Gate, passing Sorrelsykes House on the right, and following a well defined route, which, after a passing a succession of barns and stiles finally emerges into Morpeth Gate near Flanders Hall. Turn right and follow the lane, which crosses the Little Beck by the picturesque Burton Bridge and rejoins the B6160 opposite Grange Farm Cottage. Turn left, and follow the lane through West Burton back to start of our walk, passing Peel House on the right. If you have time you can revisit the waterfall, or even drive to the nearby Aysgarth Falls. A fine end to a pleasant ramble.