17. THE SLEDMERE FOLLIES

Two unique and fascinating war memorials, a stately home, an ancient trackway and a tastelessly ornate prospect tower are the highpoints of this tiring but interesting ramble on the rolling Yorkshire Wolds.

Getting there: From York (ring road) follow A166 Bridlington Road via Stamford Bridge and Garrowby Hill to the village of Fridaythorpe. Turn off left and follow B1251 to Sledmere. Carpark and picnic area near entrance to Sledmere House, by junction with B1253 Duggleby Road, opposite war memorial.

Distance: 8 miles. A long hard walk, much of it on tarmac. Not recommended for small children. (Note: 'Cop out' available! As all the follies on this walk are by the roadside you could get round them by simply using the car. But you wouldn't do that - would you?)

Map Ref: SE 928 647. 1:50 000 Landranger 101 'Scarborough & Bridlington'

Rating: Follies **** Walk*

"To help to save the world fra wrong

To shield the weak and bind the strong."

The walk- Park at car park near the Eleanor Cross by Sledmere House. Proceed along the main road (B1251), passing the Waggoners Memorial on the left, and passing the entrance to Sledmere House on the right. Continue onwards, passing the Triton Inn and the Domed Canopy erected to the memory of Sir Christopher Sykes standing opposite the main gate to the estate. At the road junction ignore the B1253 leading off left to Bridlington and proceed along the B1252 (Driffield) passing estate housing and the Primitive Methodists' Chapel on the left. Just beyond houses a farm track leads off left. follow this to the Castle Farm. At Castle Farm turn right, and follow the farm road to rejoin the B 1252. From here a long weary trudge leads to the Tatton Sykes Monument on the summit of Garton Hill.

After examining the Monument turn right along a grassy track (signed Public Bridleway) running to the left of a stand of trees. Follow this long, pleasant promenade until encountering a metalled lane leading up towards two blocks of houses on the hilltop. Turn right up lane back towards Sledmere, a long (and wearying!) tramp which passes Life Hill on the right to rejoin the B1251 leading into Sledmere. Turn right for Sledmere House and the start of the walk.

The story of Sledmere is the story of the Sykes Family, who turned a remote sheepwalk into some of the finest arable farmland in England and in so doing stamped their personalities irrevocably upon the local landscape. Our walk starts outside their house, which was first opened to the public in 1965, and which, despite the summer incursions of tourists still manages to remain a 'lived in' family home.

Sledmere House, its black & gold gates guarded by Tritons, is the last of a line of houses. The first, (Tudor) house was inherited by Richard Sykes in 1748. The Sykes' family originated from Leeds and had made their fortunes from wool throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. Richard Sykes inherited Sledmere as a result of his father's marriage to Mary Kirkby, who was a descendent of the Kirkby family of Cottingham, and thus heiress to the Sledmere Estates.

Richard Sykes soon made his mark. Demolishing the manor house he built himself a Queen Anne Mansion in brick. This in turn passed to his brother Mark, who in 1733, as Vicar of Roos was the only clergyman ever to be made a baronet.

His son, Sir Christopher Sykes, really began Sledmere's 'agrarian revolution' when he took over managing the estates in 1776, and after the death of his father in 1783 he turned his attentions to the house and park. Aided by the architect Wyatt, and the famous landscape gardener 'Capability' Brown, he created a 2000 acre park which resulted in the uprooting of half of Sledmere Village! Two wings were added to the house and the whole building faced with Nottinghamshire Stone, the existing structure being greatly modified. By 1787 the house was complete, and Joseph Rose, an associate of Robert Adam, was employed to decorate it. Much of Rose's work was lost in a terrible fire in 1911, but much was later re-created from original drawings by the architect W.H. Brierly. In the wake of the fire 40 rooms were added (in brick) but these were demolished and cannibalised to build estate cottages after the Second World War.

Christopher Sykes had married Elizabeth Tatton, heiress to the Egerton Estates in Cheshire, and her huge wealth encouraged him to set out to 'tame the Wolds'. Enclosing the vast sheep walks, a treeless, hedgeless landscape since time immemorial, he put the land to the plough and made roads with large green verges to provide 'common' grazing. He planted over 54,000 larch trees to act as wind breaks and built farms, stables and barns. By his death (in 1801) he had created over 34,000 acres of fine agricultural land.

His son, Sir Masterman Sykes, (3rd baronet) established the Sledmere Stud in 1801, but it was his brother Sir Tatton, (the 4th baronet) who really continued from where his father had left off. Inheriting the estates in 1823 Sir Tatton was to preside over Sledmere until his death at the age of 90. Sir Tatton was 'the perfect squire' the North's real life answer to Addison's 'Sir Roger De Coverley'. He was possessed of an immense energy, and was a famous sportsman and racehorse owner. He increased the Sledmere Stud to over 300 head, and it is said that on one morning he rode over 63 miles from Sledmere to Pontefract for the afternoon's racing, overnighting in Doncaster and then pushing on to Lincoln the following day for yet more racing! On two other occasions he rode to Aberdeen for the Welter Stakes and then straight back to Doncaster to catch the St Leger!

One might be forgiven for thinking Sir Tatton a man of fashion and style, a fop, or a dandy- not so! He would work on his lands like a common farm labourer, with his coat off and his sleeves rolled up, hedging, ditching, breaking stone. No task was too menial for the energetic Sir Tatton! It was said he would befriend even the poorest tramp! Sir Tatton noticed that the grass growth was more lush by the kennels where his hounds buried their bones. This led him to experiment with bone meal as a fertiliser, and to devise machinery for the purpose of bone crushing. He was man of many parts!

His son, the second Sir Tatton, inherited Sledmere in 1863. As a young man, his father had frequently sent him on long journeys abroad, basically to get him out of the way. His memories of his father therefore, were slightly less than fond. On inheriting the estates, young Sir Tatton wasted no time in instituting his own personal, somewhat autocratic regime. At Sledmere House he had the lawns and flowerbeds ploughed up and his villagers banned from growing the 'nasty untidy things' around their cottages. For reasons best known to himself, he forbade his tenants to use their front doors, a bizarre and baffling measure! Young Sir Tatton however, did have his positive side. He was a social reformer, a builder of churches and a dedicated educationalist. He built 5 new schools, and, with the aid of the architect Temple Moore, rebuilt or restored upwards of 20 churches all over the East Riding, at a cost of over £2,000,000!

The church at Sledmere is a classic example of his work. Only the lower part of the tower remains from the original mediaeval structure. It was rebuilt by Temple Moore in 1898. The interior is filled with fine woodwork,sculpture and stained glass.

Young Sir Tatton died in 1913 and was succeeded by Sir Mark Sykes, who was the last great builder at Sledmere. Young Sir Mark was a famous traveller and diplomat, and had spent a lot of time in the Middle East. He had been involved in political negotiations in Arabia, Egypt and Syria, and had come up with the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. A founder of the Arab Bureau, he was associated with Lawrence of Arabia, which alone was enough to give him a romantic air.He died, (appropriately enough) while at the peace conference in Versailles. Above all, Sir Mark was a soldier, and it was as such, that he left his most lasting memorial on the landscape of Sledmere.

Having visited House and Church, we come to the main object of our visit - the follies. It might be argued that a war memorial is not a true 'folly', that the appellation might in fact, be construed as insulting when applied to a structure which commemorates the fallen of two world wars. But in the case of Sledmere's two war memorials, I feel we can make an exception. Without disrespect to their purpose their sheer uniqueness and eccentricity makes them worthy of inclusion in this book.

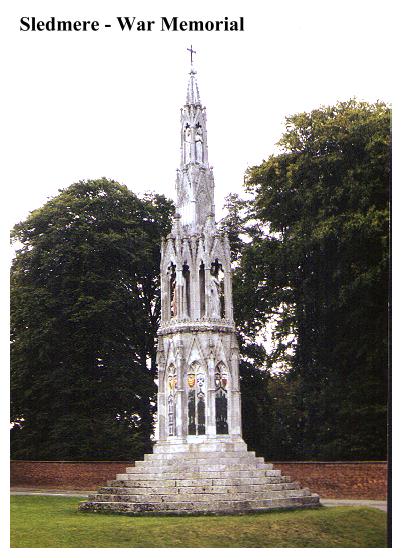

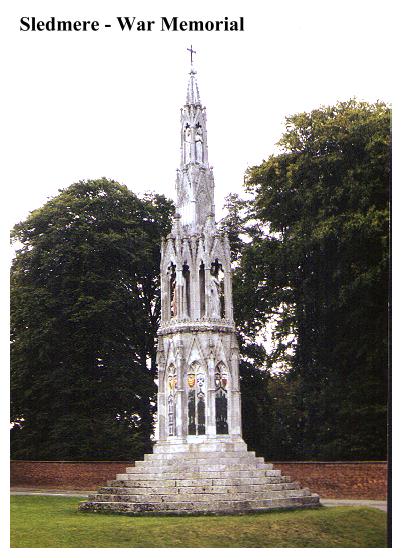

The main War Memorial in Sledmere takes the form of an Eleanor Cross. This is in fact a true 'folly', as it was not originally built as a war memorial, being 'converted' to one in 1919. The original 'Eleanor Crosses' were of course built in the 13th century by Edward I. He was married to Eleanor of Castile, and when she died in Nottinghamshire in 1290, Edward in his grief vowed to build a cross to her memory at every place where her body rested on her way to burial at Westminster Abbey. 3 'Eleanor Crosses' survive, and this Sledmere 'pastiche' is based on the one at Northampton. It was erected in 1895-1900 by 'young' Sir Tatton Sykes,the architect (predictably enough!) being Temple Moore. It is 60 feet high and rises with a sweeping gracefulness from an impressive base of steps. After The Great War it became a memorial to 23 local men who did not come back. Sir Mark Sykes 'conversion' of the cross was tasteful,imaginative and,(in a romantic kind of way) bordering on the eccentric.

Basically all he did was to add a series of brass portraits of the fallen, but these portraits are executed in such a clever way that they blend in with the 13th century style of the monument and imbue the drab khaki and puttees of 1914 with a chain mail and armour imagery evocative of Crecy and Agincourt. Raymond Thompson has a chained figure of war at his feet, two Sledmere joiners have their tools engraved in brass, and, in an eastern setting, we see Sir Mark himself with his feet on a vanquished warrior. Major Brown has an eagle at his feet with a small figure of Joan of Arc at his head. Each figure depicted has its own unique fascination.

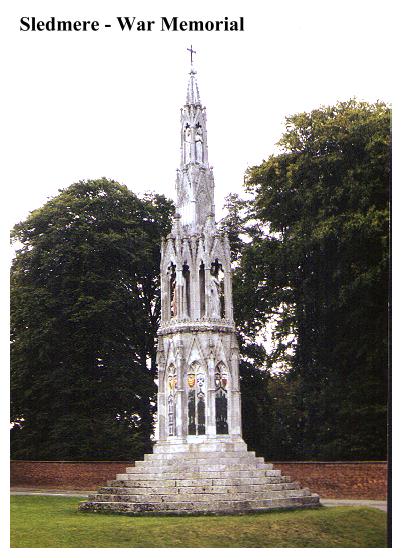

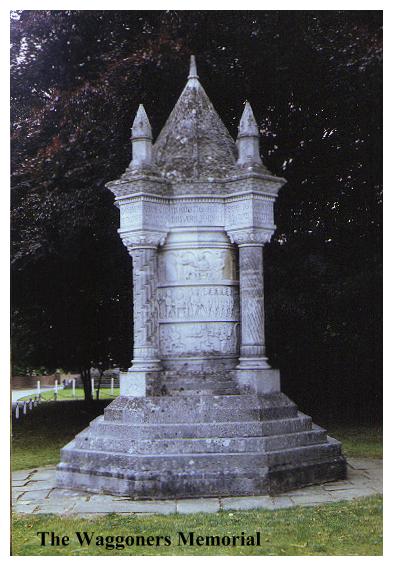

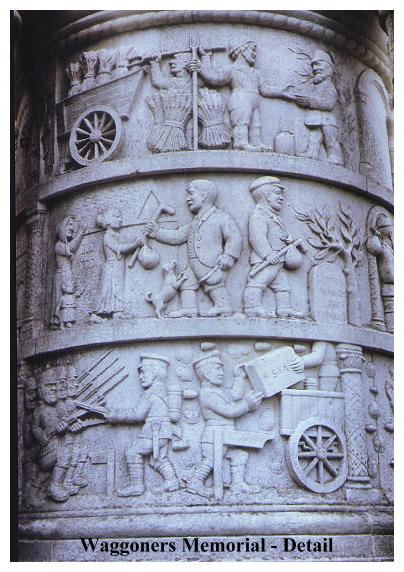

A Short distance down the road is the Waggoners Monument. Here, frequently noticed by the passing motorist but seldom visited, is what must be the most eccentric and unusual war memorial in Britain! War Memorials tend to fall into three basic types- stone monoliths, statues and mausoleum-like structures which range from the parochially minute to the municipally gigantic. The Waggoners Monument conforms to none of these. Imagine Trajan's Column in Rome squashed into a fat squat cylinder and enclosed by a conical roof and restraining pillars and you will be getting somewhere near the mark!

The Waggoner's Monument is delightful! This astonishingly eccentric sculpture was designed by Sir Mark Sykes, who raised a company of 1200 local men to fight in the Great War. This monument tells, in a manner worthy of Marvel Comics, their true story. We are introduced to the Waggoners with a series of verses, which are carved on mosaic tablets in a strange, sinuously fanciful script. As if to bind the spell, the verses are in dialect:-

I. These steans a noble tale do tell,

of what men did when war befell,

and in that 'fourteen harvest tide

the call for lads went far and wide

to help to save the world from wrong,

to shield the weak and bind the strong.

II. When from these wolds XII hundred men

came forth from field and fold and pen

to stand against the law of might

to labour and to dee for right,

and for to save the world from wrong,

to shield the weak and bind the strong.

III. These simple lads knew nowt of war,

they only knew that God's own Law

which Satan's will controls must fall,

unless men then did heed that call

to gan to save the world from wrong

to shield the weak and bind the strong.

IV.Ere Britain's hosts were raised or planned

the lads whae joined this homely band

to Normandy had passed o'er sea,

where some were maimed and some did dee,

and all to save the world from wrong,

to shield the weak and bind the strong.

V.Good lads and game, our Riding's Pride,

these steans are set by this roadside,

this tale your children's bairns to tell

of what ye did when war befell,

to help to save the world from wrong

to shield the weak and bind the strong.....

LT COL SIR MARK SYKES BART.MP. DESIGNED THIS MONUMENT AND SET IT UP AS A REMEMBRANCE OF THE GALLANT SERVICES RENDERED IN THE GREAT WAR 1914-18 BY THE WAGGONERS RESERVE A CORPS OF 1000 DRIVERS RAISED BY HIM ON THE YORKSHIRE WOLD FARMS IN THE YEAR 1912. THOMAS SCOTT FOREMAN- CARLO MAGNANI SCULPTOR- ALFRED BARR MASON.

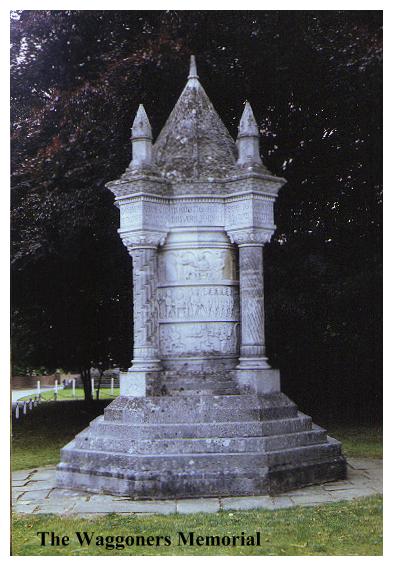

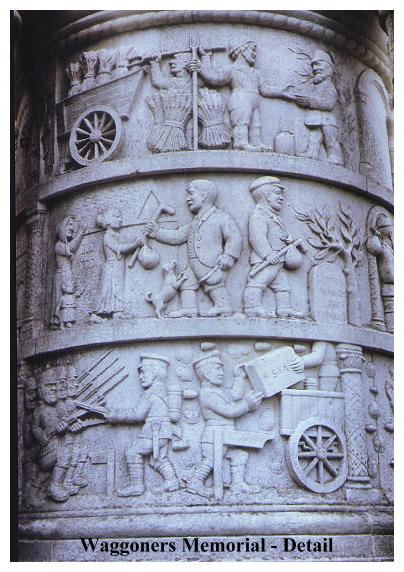

But the greater part of the story is told in pictures- for the whole monument is a delightful tableau of larger than life comic strip caricature. We see the labourers in the fields at harvest time, we see them joining up, we see the soldier saying goodbye to his family, his little dog jumping at his heels. We see the crossing to France, even the mines and fish in the channel! Snarling spike helmeted Germans burn a church and drag a screaming woman by the hair, as our 'good lads and game' arrive to 'save the world from wrong'. The retreat from Mons is depicted, as shells fly through no mans land, and grimacing huns fix bayonets with bared wolf-like teeth, before being beaten and chased across a bridge over the Marne. Today the 'steans' still 'tell of what men did', and one cannot help but think that Agincourt and Shakespeare's Henry V must have been uppermost in Sir Mark's mind when he planned both monuments. Sadly, he died prematurely at the age of 39, and never lived to see the completion of his monuments.

Sledmere's third folly is some distance down the road, beyond the village hostelry, the Triton Inn. Standing opposite Sledmere's entrance gates it is essentially a classical Rotunda, (similar to that at Wentworth Woodhouse) which was erected over the village well in 1840 by Sir Tatton Sykes (the first),as a memorial to his father. The inscription tells all:-

"This edifice was erected by Sir Tatton Sykes,baronet, to the memory of his father, Sir Christopher Sykes, baronet, who, by assiduity and perseverance in building and planting and inclosing on the Yorkshire Wolds in the short space of 30 years set such an example to other owners of land as he has caused what was once a blank and barren tract of country to become now one of the most productive and best cultivated districts in the County of York. AD 1840.".

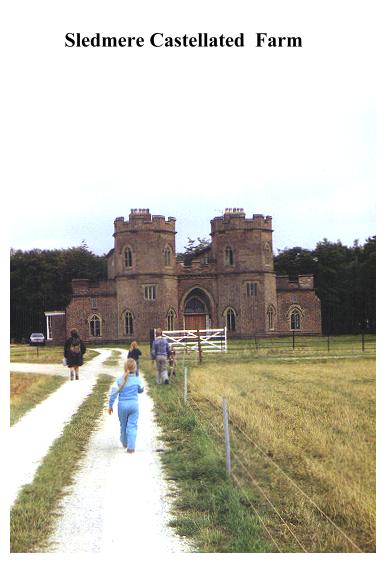

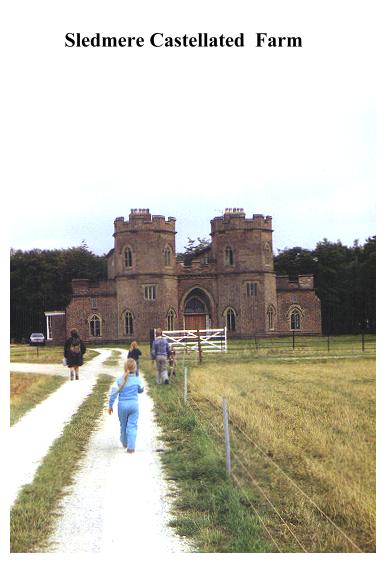

Leaving Sledmere our route follows the farm track out to Sledmere Castle Farm, which was built as an 'eyecatcher' for 'Capability' Brown's landscaped park. This is the oldest folly in the Sledmere group, being built by Sir Christopher Sykes around 1776. It was apparently intended as a dower house, but was never used as such. Informed opinion tells us that the house was almost certainly designed by John Carr. However,other likely candidates include Joseph Rose, 'Capability' Brown and even Sir Christopher himself! Basically its facade is that of a castellated gatehouse with twin towers. It was first used as a farm around 1895.

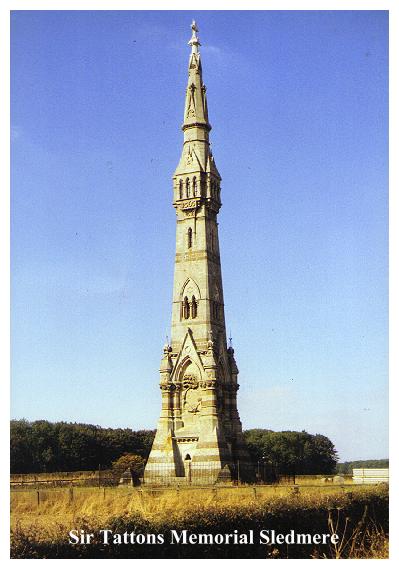

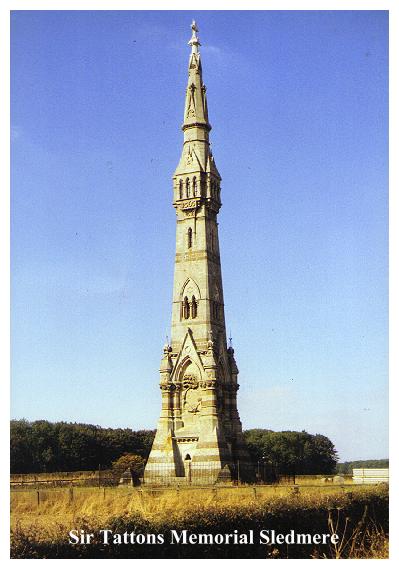

The final folly in the Sledmere Group, Sir Tatton's Monument, is reached by a long slog (about three miles) along the B 1252. Standing on Garton Hill overlooking Garton-on-the Wold, this is without a doubt the finest prospect tower in East Yorkshire and one of the best follies in Britain. This lavish monumentwas designed by J. Gibbs of Oxford, in grey and brown stone. It stands around 120 feet high and was erected in 1865 by the tenantry in memory of Sir Tatton (the first!) who had died two years previously. At the base of this grossly gothic structure is a door, above which sits a bas relief of Sir Tatton on horseback, surveying his estates. An internal stairway leads to an observation room with oriel windows (The tower is not open to the public). An inscription, which runs as a frieze around the tower informs us that 'THE MEMORY OF THE JUST IS BLESSED'. The whole thing is crowned by an ornate cross on a pinnacle. Standing in such an exposed position as this, it is amazing that this delightfully ugly creation has remained in such pristine condition for 125 years. Across the road a stylistically similar house plays sentinel. Perhaps this is one of the reasons.

The rest of our walk is relatively unspectacular. The track which leads from the monument along the hillside (Green Lane) gives us a fine and undisturbed view of the magnificent wolds landscape. Ancient history is writ large hereabouts. On these hills once lived the Celtic Parisii, and their burial mounds and earthworks lie all around, Green Lane running along the line of their defensive dykes. In their wake came the Roman Legions, who constructed two major roads (High Street and Low Street) across the Wolds, both of which passed close to Sledmere. Here,on Green Lane, we are actually walking along the line of the Roman 'Low Street' which led from York to Bridlington. Beyond the Sykes Monument it led on to Kilham, and from there (as the Wold Gate) it led past Boynton to the coast.

Beyond Green Lane the rest of the walk is weary trudge on tarmac back to Sledmere. In effect we are walking around the perimeter of the park. Tantalising tracks lead off into the Sykes domains, but all is private, and there is no scope for the rambler. In this respect the walk is a disappointment, and many people I am sure will be tempted to explore the whole thing by car and move on to more accessible countryside elsewhere (Carnaby being the most obvious choice). Only on ancient Green Lane do we get a taste of the emptiness of the rolling Wolds, along with a vision of days gone by as we plod along a seemingly endless ribbon of velvet turf. Perhaps this alone makes the BMW dodging worthwhile, but then again, if you parked up at the Sykes Monument you could walk Green Lane in both directions and get the best of all possible worlds. Folly tour and stroll? or long march? In the end the choice must be yours!