3.ELLESMERE MEMORIAL AND WORSLEY

On this pleasant walk on the urban fringe of Manchester we encounter boats, canals, woodlands, a lake with wildfowl, a excellent (if inaccessible) folly, and visit Worsley Delph - the cradle of the Industrial Revolution

Getting There: M62 to Junction 13. From roundabout, take first junction off towards Alder Forest. Turn right into carpark just before reaching the bridge over the canal (the Packet House is on your left).

Distance: 4 Miles approx.

Map ref.: SD 748 004. Ellesmere Memorial SD 735 009

Rating: Walk** Follies and General Interest ***

Worsley is the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, and a suburb of Salford. These statements might lead you to think that Worsley is a depressingly grimy sort of a place, yet nothing could be further from the truth.

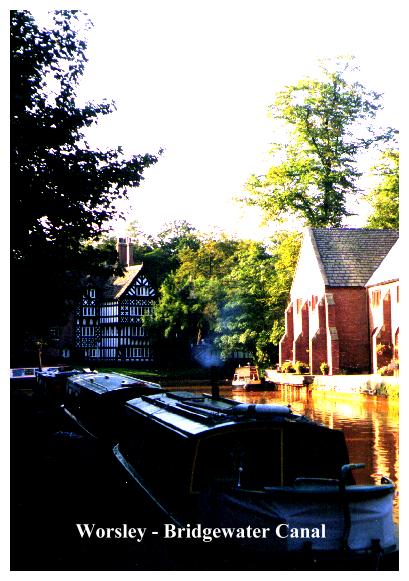

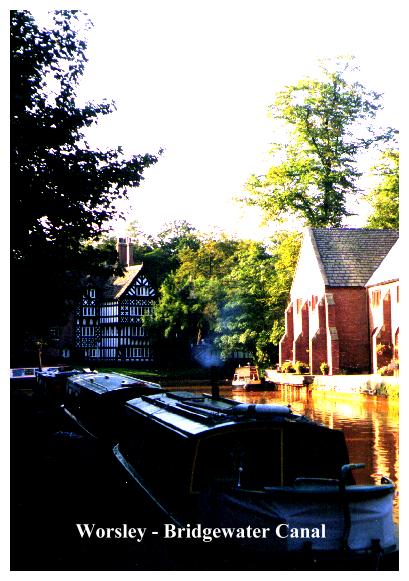

Worsley is delightful. Yes, much of it is a built-up area, and there are numerous busy roads, but it is not those images which linger in your memory. What remains rather is a vision of gentle woodlands, timbered Tudor-style buildings and the tranquility of the Bridgewater Canal, with its orange waters and beautifully-adorned canal boats.

Our perambulation starts and finishes by the canal. The local council have recognised the historical significance of the area and have obligingly provided a history trail marked by large noticeboards that outline the story of the area. These are illustrated and are of great interest.

The story of Worsley is essentially the story of two men, the one an eccentric aristocrat and the other a half-literate Derbyshire millwright. According to the legend, lovesick Francis Egerton, the third Duke of Bridgewater, having broken off his engagement to the Duchess of Hamilton, decided that he would devote the rest of his life to commerce. To do this he engaged James Brindley, a millright, to construct a canal that would take the coal from his Worsley mines to the markets of Manchester, and by so doing constructed Britain's first artificial waterway and unwittingly launched the Industrial Revolution.

So much for the legend. The truth, however, is somewhat less romantic. For one thing Egerton was no lovesick fool. His works in Worsley were already well underway before he broke off his engagement. As to his canal being the first modern man-made waterway, this is also not strictly correct, for the Sankey Brook navigation near St Helens had already claimed that distinction in 1751.

The rest, however, is basically true. Egerton had a problem, and he solved it with great ingenuity. It was only seven miles to Manchester, but to transport coal there by packhorse was inefficient and expensive. Egerton realised that the only answer was a 'navigation', and after removing potential opposition by getting a private act passed in Parliament, the duke finally began work on his Bridgewater Canal.

The rest is history. He employed James Brindley (whom he never properly paid for his services) to construct the canal. Brindley was semi-literate, and had no experience of waterways, but was a man of great intelligence and engineering genius.The canal was (and still is) supplied by water from Bridgewater's mines, and during the course of its journey to Manchester it crossed the Irwell by the Barton Aqueduct - an incredible feat of engineering for the time, and the wonder of the age. The canal was completed in 1765.

So to our walk. The first place of interest we encounter is the Boathouse on the oppposite side of the canal. This was built by Lord Ellesmere (Bridgewater's great nephew) to house a royal barge especially constructed for Queen Victoria's visit in 1851. The boat was pulled by two grey boat horses, one of which, being nervous,shied and fell headlong into the cut!

Beyond the Boathouse we cross the canal via the Hump Backed Footbridge which was built by Lord Ellesmere in 1901. We cross tranquil Worsley Green, surrounded by its tudor-style cottages to take a look at The Fountain, essentially a red-brick structure containing an urn. Few people would imagine that 200 years ago this peaceful spot was an industrial eyesore, for the green was originally the works yard, criss-crossed with tramways, and the fountain was the base of a smoke belching factory chimney. The yard was demolished in the early 1900s, and the surrounding cottages built soon after. The Fountain commemorates the duke and his acheivements and carries an inscription in Latin which Henry Hart Davies translated in 1905 as follows:-

'A lofty column breathing smoke and fire,

Did I the Builder's glory once aspire,

Whose founder was that Duke who far and wide

Bridged water through Bridgewater's countryside.

Stranger! this spot, where once did never cease

Great Vulcan's year, would sleep in silent peace,

But beneath my very stones does mount

That water's source, his honour's spring and fount.

Alas! that I who gazed o'er field and town,

Should to these proportions dwindle down.

But all's not over, still enough remains

To testify past glories, duties, pain.'

Crossing the green to the main road, we bear left and soon arrive at Worsley Delph, which, more than anywhere else, was the birthplace of and raison d'Útre for, the Bridgewater Canal.

Worsley Delph, as its name suggests, was originally a quarry. Sandstone from the delph was used in the construction of Brindley's canal. The marks of the quarrymen's picks and the shot-holes for their explosives may still be seen in the sheer walls of gritstone. An arm from the Bridgewater Canal leads directly into the delph, and the whole area has been made into a substantial canal basin. At the base of the cliff, two low and spidery- looking tunnels disappear underground. Like the basin itself, the tunnels are partially silted up, and slimy looking orange water trickles out of one of the entrances. This is caused particles of ochre (iron hydroxide) being leached out of the rock, and it discolours the canal for a great distance. These uninviting-looking archways were the adits from the dukes' mines, being the source not only of the duke's coal but also of a substantial water supply to feed the canal.

Yet they were more than this. For beyond these low arches exist marvels of engineering unsurpassed by even the Bridgewater Canal itself.The duke, having planned the canal which would connect the markets of Manchester to the coal heaps of Worsley, decided he would go a step further, and extend it to the underground coal face itself.

This amazing system of subterranean waterways was begun in 1759, soon after the excavation of the Bridgewater Canal. It was largely the work of the dukes' overseer, John Gilbert. The twin tunnels we see in the delph unite after about 500 yards and lead into a labyrinth of canals which are around fifty two miles in extent and constructed on four levels. These extensive stygian highways extended into the Worsley coalfield even as far as Walkden and Farnworth, connecting into and draining most of the mines in the area. How, you might ask, was it possible to have a usable canal operating on four different levels? John Gilbert's answer was both simple and ingenious- underground canals led to the top and bottom of a dry incline and, using a system of trolleys, pulleys and locks, the weight of a laden boat descending under gravity drew the arriving unladen boat up the incline. The passage of the boats along the adits was assisted by sluice gates, which opened to release the build up of water behind them, creating a wave which propelled the boat along.

The duke's underground canals ceased to carry coal in 1889, but the tunnels were regularly inspected right down to the 1960s as they drained other mines in the area still operating. Today they are left with their memories and the ghosts of the duke's miners - men, women and children, who laboured in the darkness for up to fourteen hours a day crawling on hands and knees in dim candlelight. Theirs was the real achievement, and it should not be forgotten.

Beyond Worsley Delph we come to the real treat of our walk - Worsley Woods. This extensive area of woodland contains nature trails, a lake with wildfowl and picturesque cottages, and passes beneath that more recent feat of engineering, the M62. The woods were originally owned by the duke and then by the 1st Earl of Ellesmere, who planted much of the woodlands and created the network of footpaths. It was the earlwho constructed the Old Warke Dam for fishing and boating, and the lovely house known as 'The Aviary' which is currently being restored.

From the woods, we pass through an uninteresting housing estate and cross a busy road before reaching pleasant countryside once more by Worsley Old Hall. This is now a restaurant, but was originally the centre of the dukes' operations. After the duke died in 1803, his estates eventually passed to Francis Leveson-Gower. the second son of the Marquis of Stafford. In accordance with the duke's will, Francis adopted the name of Egerton, and in 1846 was created the Earl of Ellesmere. The earl was a well known philanthropist, and it is to his monument, which stands just across the fields, that we now proceed.

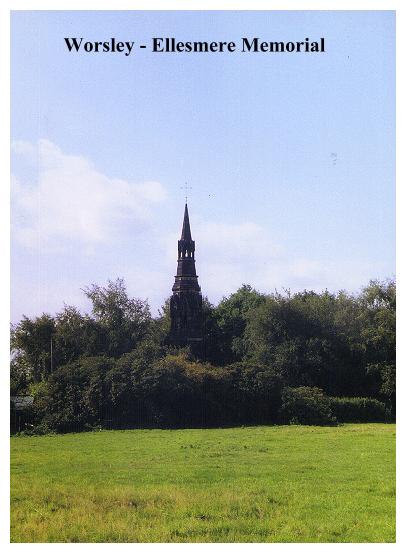

The Ellesmere Memorial is at once a delight and a disappointment. Seen at a distance, a tall gothic spire surrounded by trees, it looks good, and no doubt it is good. The only trouble is there is no way you can get to it! On the road side it has been completely cut off by housing, and on the other side it has been completely sealed in by steel fencing and pony paddocks.

My immediate reaction when faced with a situation like was to write the whole thing off. But then I decided I would write about it anyway, if only to draw public attention to the plight of the folly. For here is an ornate and interesting piece of local history which is being allowed to quietly fall down, out of sight and out of mind. There is no public access to it, and, it would seem, no private access either. No doubt the shade of Lord Ellesmere is even now turning in his grave!!

Over in neighbouring Worsley we have seen history trails, nature trails and a developing tourist attraction, yet here, just a short distance down the road, we are witnessing the triumph of private property over national heritage. It is obscene that this has been allowed to happen. In my travels all over Lancashire I have seen follies that have been renovated and restored, in some cases even privately owned ones. There is an increasing awareness all over Britain of the irreplaceable architectural heritage embodied in these eccentric structures, and happily, although many have been lost, many others have been saved before it is too late. Here in the Ellesmere Memorial is a unique structure that is about to disappear. I can do no more than to leave a simple open message to the people of Greater Manchester: What are you going to do about it?

The Ellesmere Memorial was built in 1859 to commemorate Francis Egerton, the 1st Earl of Ellesmere, whose death had been greatly mourned by those who remembered him for his good works in the 1840s when he had found work for cotton operatives whose families would otherwise have starved. He had also done much to improve the area, providing parks, playgrounds and public woodlands.

The memorial was conceived by a committee of local worthies, who set up a subscription fund, which raised £1,800 towards its construction. A competition for the best design was announced, with a first prize of 60 guineas, and the winning design was by Driver and Weber of London. The winner of the third prize, a Mr. Keeling, submitted designs for "a columnar composition, in three stages, of the Doric and Tuscan orders, Height 90 feet." The whole structure being capped by a 'glass dome, silvered like a looking glass!

The foundation stone for the memorial was laid on November 17th, 1858. An illuminated manuscript bearing the names of all the dignitaries involved in the project was sealed in a cavity in the masonry - a time capsule for posterity. The completed Memorial was opened on August 10th, 1860, when it was formally presented to the son of the late earl by Mr Fereday Smith, chairman of the monument committee.

The Ellesmere Memorial is an an ashlar structure incorporating a band of Minton encaustic tiles and corner columns of 'the new serpentine discovered at the Lizard'. The building has two main stages and a spire, which originally stood atop a tall octagonal column, since removed. The corners of the building bore heraldic finials, which were removed around 1980. The memorial is 132 feet high, and contains a spiral staircase of 125 steps. An inscription, surmounted by the arms of the earl, explains the purpose of the tower:

An affectionate tribute to the memory of Francis Egerton, First Earl of Ellesmere, K.G., from the tenantry, servants, carriers and others connected with his landed and trading interests, 1860.

At the top of the monument there is room for six people, and a view which on clear days is said to range Cheshire and Flintshire.The balcony is bounded by iron railings. Years ago, the Ellesmere Memorial was a popular local attraction, especially on Good Fridays when local people made an annual pilgrimage here to ascend the tower and enjoy the wide ranging views from the observatory at the top. Today those glories have passed, and the only visitors to the Memorial are the birds, which are undeterred by the surrounding fencing.

And so we approach to the end of our perambulation, which leads us back to Worsley Delph along the busy main road, passing the 1st Earl of Ellesmere's main architectural contribution to the area, the magnificent neo-gothic St Mark's Church, which contains the earl's tomb. Soon we are back on the canal by the Packet House, a picture postcard sort of a place, originally built in the eighteenth century. From the steps at the front of the Packet House, the Duke of Bridgewater once ran regular passenger services to Runcorn, Warrington and Manchester, a slow, uncomfortable, yet highly popular mode of transport until eclipsed by the advent of the railway age.

Here is a place to picnic, relax, and reflect upon the great achievements (and evils) which were created by the Industrial Revolution; triumphs and tribulations which are still echoed in the present day. For right or wrong, for better or worse, here, in this leafy suburb of Greater Manchester, the modern world began...