6. RIVINGTON PIKE

Overgrown ornamental gardens, woodlands, reservoirs, bleak moors, a sham castle and two prospect towers are all to be found in this most magnificent of country parks. Rivington is Bolton's Playground and Lancashire's chiefest jewel. You must take the kids!

Getting there: Awkward, but easy enough. From Bolton follow the A673 to Horwich. Beyond the roundabout turn right between gateposts into Lever Park. Great House Barn stands to the left of the Horwich- Rivington Lane.

Distance: 5 miles approx.

Map ref: SD628 138 Sheet 109

Rating: Walk*** Follies and General Interest***

Rivington is one of the great playgrounds of Northern England. Here is where Lancashire folk come to picnic, to walk, and to enjoy the peaceful countryside and the wooded glades. On a pleasant summer Sunday you will find the whole area alive with visitors. Don't let this put you off however, as there is room for everyone. You get a bit of everything at Rivington, reservoirs, parkland, woodland, moorland, overgrown ornamental gardens, waterfalls and lakes, and of course (I almost forgot) follies; three of them to be exact.

For all of these natural (and not so natural!) wonders we may thank one man, a man whose vision, benevolence and desire for escapism quite literally created the landscape we see here today. His name was William Hesketh Lever, and, among his many other accomplishments he was probably one of the last of Britain's great folly builders.

William Hesketh Lever was born in September 1851 at 16 Wood Street Bolton. His father was a wholesale grocer and a strict chapelgoer. Lever was educated in Bolton, and at the age of fifteen began work for his father, for the princely sum of one shilling per week! One of his many tasks was to cut soap to customer's requirements. By the time he was nineteen he was engaged in obtaining orders from retailers in the Bolton area, and he served the business so well that in 1872 his father made him a partner in the firm. In 1874, Lever married and settled in Park Street Bolton.

As business expanded, Lever was appointed manager of new premises in Wigan, and very soon Lever & Co had become one of the largest wholesale grocers in the North-West. Lever's secret was the use of what in those days was quite a novel idea - advertising.

Yet Lever went further. He was to invent something that would eventually become quite ubiquitous- the Trade Brand. Lever wanted to create a product with his own distinctive trademark that no-one could copy. The product he chose was soap, and the name he decided upon was Sunlight.

Sunlight Soap was launched with an intensive advertising campaign. The name even appeared on the back of postage stamps! Where soap had been traditionally been cut to demand, Lever bought it direct from the manufacturers, had it stamped, cut into individual standard measures and packaged. It proved to be an instant and phenomenal success.

A large factory was opened near Birkenhead in 1889. Lever decided that he wanted to house his ever expanding workforce near the means of production, so he began work on a 'model village' with lawns, wide roads and spacious houses, each with its own garden. This village he called Port Sunlight, and by the standards of the time it was positively luxurious!

By 1900, Lever had created an empire, with factories in Europe and America. When he died in 1925, weighted down with honours, Lever had £50,000,000 in issued capital and over 100,000 employees.

William Hesketh Lever, Lord and later Viscount Leverhulme, did not forget his humble Bolton origins, neither did he desert the town and the Lancashire people he had always known so well. At various points in his career he was Liberal MP for the Wirral and the Lord Mayor of Bolton. He established museums and churches, he endowed universities and schools, amassed a large art collection and gave public lectures in which he advocated a six hour day for industrial workers.

Yet Lever's abiding interest was in landscape design and architecture, a pastime in which he indulged at every available opportunity. He purchased the Rivington Hall Estate in 1899 for £60,000, and it proved to be the ideal place in which to give this passion for landscaping a free hand.

At Rivington, Lever created Britain's first ever 'country park' in the modern sense of the word. Forty five acres below Rivington Pike he kept back for himself but the rest he donated to Bolton Corporation in 1902 for the enjoyment of the general public. Lever converted two barns into refreshment rooms, turned the hall into an art gallery and populated his paddocks with exotic animals. He laid out roads, avenues - and follies. Lever Park was officially opened on 18th May 1904 with a further ceremony in 1911 to celebrate the completion of the building work. The two obelisks by the entrance to the park were erected after Lever's death.

Our walk begins at Great House Barn where there is a car park, a cafe and an information centre. This barn reputedly dates back to Saxon times, but has been much restored, first in the 1700s and then by Lord Leverhulme. The roof is held up by two huge crucks, which are essentially the two halves of a tree sawn down the middle with tie beams held together by wooden pegs. The barn, along with its sister Great Hall Barn is thought to have once been a tithe barn, where a 'tithe' or tenth of the local grain produce was stored for the upkeep of the clergy.

From Great House Barn our walk proceeds to the shores of Rivington Reservoir. This was built between 1852 and 1857. It is part of a chain of reservoirs which were originally constructed under the Rivington Pike Scheme to provide water for Liverpool's thirsty masses. The reservoirs in the Rivington area hold around 4,000 million gallons, and still supply Liverpoool with around 11.5 million gallons of water a day.

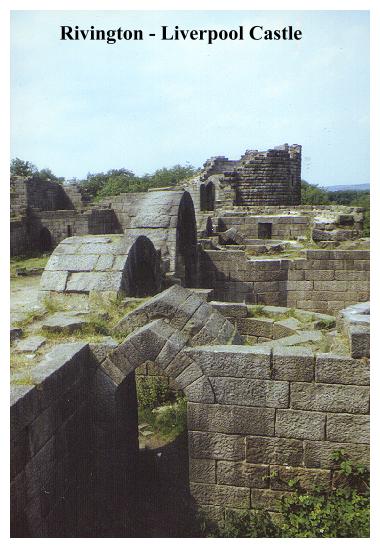

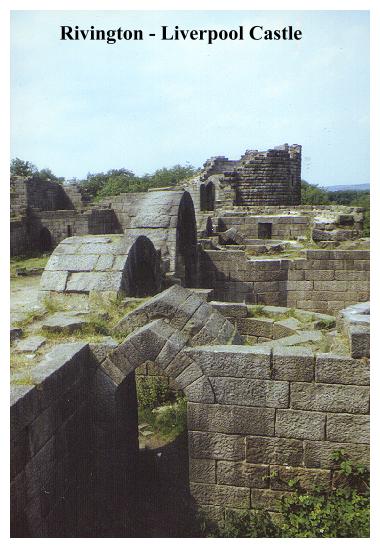

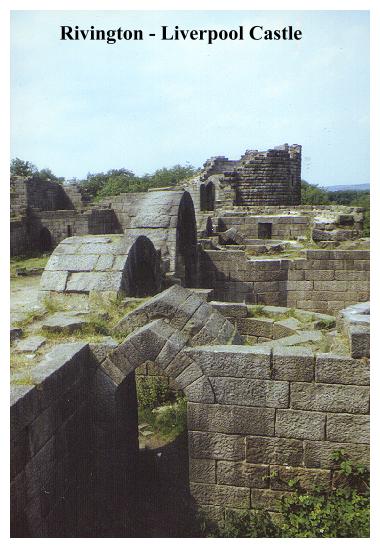

So, having walked along the lakeside we come to Lord Leverhulme's first great folly, Liverpool Castle, a sham ruin. The original Liverpool Castle once stood on the site of the present Queen Victoria Statue in Derby Square, Liverpool. It was demolished in 1720 to make way for a church. Lord Leverhulme began work on his replica around 1911-12, and work continued on it right down to 1930. The architect was reputedly Thomas H Mawson, the landscape gardener who laid out the park and with whom Lever enjoyed a fruitful working relationship, but it seems more than likely that most of the design work was done by Lever himself. The castle was never completed, but perhaps it was never intended to be. Maybe it was meant to be a sham ruin from the outset. It also has a ghost - quite an achievement for a twentieth century century baronial castle. It is reputedly haunted by a white- robed figure, as witnessed a number of years ago by five council workmen who watched it for over two hours as it glided around the castle precincts.

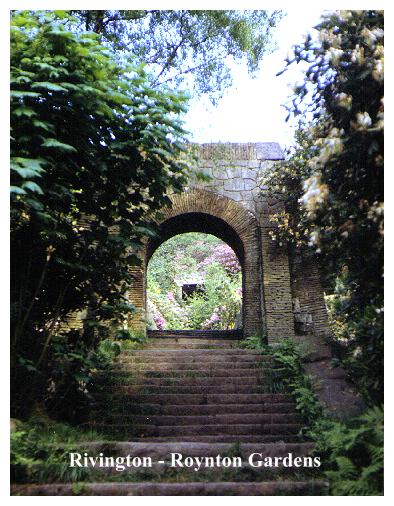

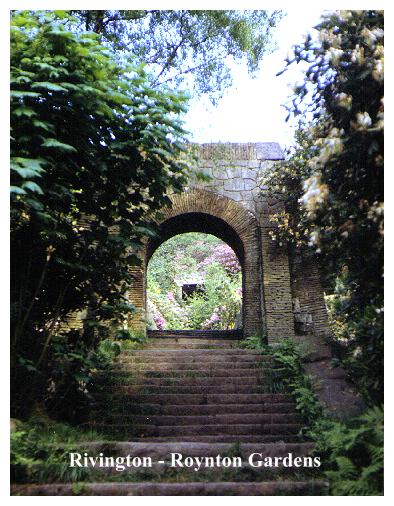

Our route proceeds along one of the Lever Park 'avenues' before heading up the hillside towards the Roynton Gardens. Here were the forty-five acres Lord Leverhulme reserved for himself - his private pleasure gardens. Work began here in 1900 and continued in various phases right down to 1925. During the second world war the gardens passed to the War Office before eventually being bought by Liverpool Corporation Waterworks, during which time they became dilapidated and overgrown - and remain so, although sections of undergrowth have now been cut back and paths waymarked to create a Terraced Gardens Trail. A map of this trail is available at the information centre.

It is hard to describe the Terraced Gardens. There is nothing anywhere quite like them. The whole area is one of overgrown terraces, grottoes, loggias, arches and steps, a jungle labyrinth of ornamental pathways leading along and up and down the steep wooded hillside. It is a folly hunter's paradise. Our route joins the gardens at the Ravine which was constructed in 1921 to designs by T H Mawson, a seemingly chaotic jumble of manmade waterfalls, footbridges, stepping stones and rockpools, cunningly contrived to look as natural as possible. Nearing the top we arrive at the overgrown remains of the Japanese Garden, perhaps Mawson's greatest creation, laid out in 1922 and undoubtedly inspired by Lord Leverhulme's visit to Japan in 1913. In its heyday it featured teahouses, waterfalls, lanterns and an ornamental lake, as well as a vast variety of exotic trees and shrubs. All of this is now buried beneath scrub and rhodedendrons.

Reaching the top of the gardens, we come to a track running alongside open country, and beyond it a further track which winds up the hillside to the summit of Rivington Pike. The pike, which is about 1,200 feet above sea level, is the oldest folly you will find at Rivington, being constructed for one John Andrews in 1733. Why he built it is not known. Like most builders of follies he probably built it merely to make his mark on the landscape - or to mark out the boundary of his estates perhaps. The tower is 17 feet square and 20 feet high, and has a faintly Babylonian appearance. In the days before it was walled up, it had a wooden roof, four windows, a fireplace and a cellar. Shooting parties from Rivington Hall once used it as a shelter. Perhaps, like the folly at the base of Roseberry Topping in North Yorkshire, it was constructed with that purpose in mind. In 1902, when Liverpool Corporation purchased the pike from Lord Leverhulme, they proposed demolition, but such was the public outcry they were forced to desist, consequently donating the tower to Chorley Rural District Council in 1912. Today the tower is protected as a grade two listed building.

Of course Rivington Pike, like many prospect tower locations, has long been a site of topographical significance. It was once part of the beacon chain and may have been in use as such as early as the twelfth century. The Rivington beacon's neighbours were Ashursts Beacon and Billinge Beacon, both of which are visited in this book. It is recorded that on the night of the 19th July 1588 the beacon was lit to warn of the Spanish Armada. Other beacons have been lit on Rivington Pike since those turbulent times. The coronation of George V, the ending of the First World War, Queen Elizabeth's silver jubilee in 1977 and the royal wedding of 1981 have all resulted in celebration bonfires on the pike.

The view from the pike, like all the landmarks on these western hills, is excellent. The Lancashire coast, Blackpool Tower and Southport's gasometer are usually in view, as is Ashurst's Beacon and, if you are lucky, the power station at Heysham. The prospect eastwards, however, is blocked off by the great bulk of Winter Hill with its Belmont TV transmitter. On a exceptionally clear day you should be able to see the Lake District, the Isle of Man and the Welsh mountains.

The landmark plays host to the Pike Race and the Pike Fair. The first Pike Race was held in 1892, and has been regularly run since. It is held on Easter Saturday and is entered by hundreds of runners. The race starts from the entrance to Lever Park. The Pike Fair, too, is still observed. It is held on a Good Friday and attracts large crowds. Last but not least, there is reputedly a spectral horseman in the vicinity of the pike, but you are unlikely to see him on a busy bank holiday!

Descending the pike, we retrace our steps back down to Lord Leverhulme's gardens. A short stroll and we soon arrive at the open terrace that was once the site of Roynton Cottage, his private bungalow. Little remains now except for a few tiles in the grass. The first bungalow to be constructed on the site, in 1901, was a temporary prefabricated affair built of timber which, despite the description, was luxuriously appointed, and surrounded by beautifully-laid-out lawns. The bungalow was intended to be used for shooting weekends and short visits. Its life was somewhat short-lived, however, for on the night of the 7th July 1913 it was deliberately burnt down by Edith Rigby, an active suffragette, while the Levers dined with King George V, Queen Mary and the Derbys at Knowsley. The whole thing must have been a shock, for Lady Lever died just three weeks later.

Undaunted, Lever built a a second Roynton Cottage, this time in stone, and at a cost of #30,000. It was completed in 1914 and a few years later a magnificent circular ballroom was added, with a forty four feet diameter sprung floor of oak parquetry and a glass domed ceiling. Leverhulme's dome was designed by R Herman Crook and depicted the stars as they appeared on the date of Lever's birth. All this, along with the three entrance lodges, was demolished by Lever's old adversary Liverpool Corporation in 1948, in the face of massive public opposition.

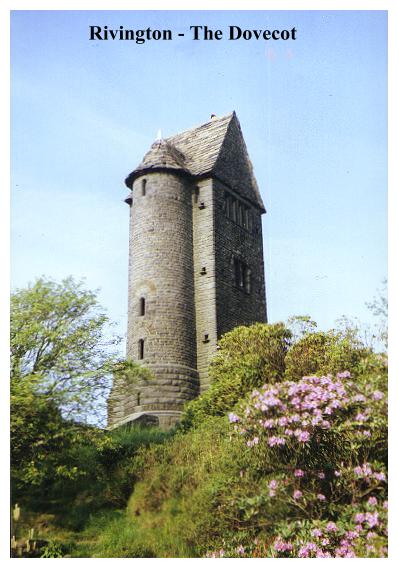

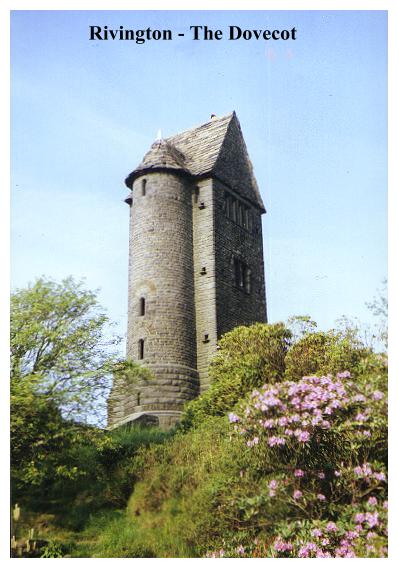

And so we arrive at what must surely be Rivington's finest folly - the 1910 Pigeon Tower or Dovecot. This was designed by T H Mawson as a piece of Scottish baronial fancy. Lord Leverhulme had interests in the Hebrides,and his Scottish aspirations are perhaps reflected in the architecture of this tower. It is said that the top floor of the tower was used by Lady Leverhulme as a sewing room, where she could enjoy the views. The lower two floors apparently housed the pigeons. By 1975 the tower had become little more than a ruined shell, but it has now happily been re-roofed and restored at a cost of around £5,000, yet another lucky beneficiary of the 1980s fashion for conserving old buildings.

From the Dovecot we descend steps - lots of them. The whole descent is one of terraces, balustrades, arches, paved causeways and loggias - all overgrown. Soon we arrive at the Swimming Pool, a murky pond where Lord Leverhulme once used to take his morning dip; and beyond we descend through rhodedendrons to emerge on top of the Seven Arch Bridge over Roynton Lane which was built in 1910, and reputedly designed by Lever himself. Beyond we bear left, then right, eventually leaving the gardens by the site of the South Lodge, which, before it was demolished, had a thatched roof.

And now we near the end of our journey as our route descends back to Lever Park, joining a tree lined avenue to the left of Rivington Hall. Here was where Lord Leverhulme had his art gallery. The present hall is largely Georgian with nineteenth century additions, although there has reputedly been a manor on the site for almost a thousand years. The fine red-brick west front was built by Robert Andrews in 1774, but there are earlier fragments as evidenced by a lintel in the west wing dated 1694.

From Rivington Hall we follow a wide avenue back to Great House Barn and the car park. This is the end of our follies perambulation, but by no means the end of what Rivington has to offer. A right turn along the road leads on to Rivington village, where an early Unitarian chapel dating from 1703 and a Tudor Church (1540) are but two of the attractions on offer. For the energetic there is the orienteering course, the Anglezarke Woodland Trail, and for the would-be-industrial archaeologist there is a trail to Lead Mines Clough. These walks also tie in with the Roddlesworth Nature Trails which we touched upon in our visit to Darwen Tower. For the folly hunter wishing to combine interest in follies with marathon walking there is a Three Towers Walk which connects Rivington Pike with Darwen Tower and the Peel Monument on Holcombe Moor. All this information is locally available. Rivington, you will find, is an enchanting place.