16. THE ULVERSTON FOLLIES

On this long walk we visit a sham lighthouse, a ship canal, a Buddhist institute, a mysterious triangular mausoleum and a house associated with the founder of Quakerism. Also featured are fine views to the Lake District, a seaside stroll and last, but by no means least,'Stan and Ollie'.

Getting There: From M6 Junction 36, follow the A591 a short distance then turn onto the A590 Barrow-in-Furness trunk road. Drive to Ulverston via Newby Bridge. Park in the town centre.

Distance: 14 miles approx

Map ref: SD285 785. Hoad Monument 295 791

Rating: Walk*** Follies and General Interest ***

Conishead Priory is open from 1-5 pm Sat/Sun/Bank Holidays, Easter to the end of September. House tours are available and there is a souvenir shop and coffee bar.

Ulverston is perhaps the most distant outpost of Lancashire to be visited in our search for follies. Situated on low ground between the sands of the Leven Estuary and the rocky outliers of the Lakeland Fells, this cozy little town straddles the busy Barrow-in-Furness trunk road. Today, like the rest of 'oversands' Lancashire, Ulverston belongs to Cumbria, but it traditionally owed its identity to its position at the terminus of the old coach route across the sands from Lancaster, the crossing of the Leven estuary from Flookburgh being the last leg of what was once a long and hazardous journey.

Certainly Ulverston has ancient roots. Its name appears in the Domesday Book, and the original settlement is believed to be Saxon. In the twelfth century it was owned by Stephen of Blois (Henry I's nephew), but eventually it became the property of Furness Abbey, whose monks retained it up to the Dissolution. Most of present day Ulverston however, is of eighteenth century origin. It enjoyed such an immense prosperity that the town once boasted the title of the 'London' of Furness. Much of this prosperity was due to the arrival of the Ulverston Canal in 1759, which encouraged the town's development as a port, and the construction of the turnpike in 1763. By the mid nineteenth century the canal had been eclipsed by the Furness Railway, yet the town's prosperity remained undiminished as it continued to sell its slate, cotton, leather and ore.

Today Ulverston's biggest employer is the Glaxo chemical plant, which lies alongside the canal to the east of the town. There is also a thriving tourist industry. Ulverston's street markets, held on Thursdays and Saturdays, attract the crowds, and there is also a livestock auction on the Thursday, which is known locally as 'L'ile Pig Day'. Tourists also flock to Ulverston's Laurel and Hardy museum, for Stan Laurel was born here in Argyle Street in 1890.

This particular ramble is quite a long one, so prepare well. Our route starts out along Church Walk, passing an interesting little gazebo on the left, at a junction of lanes. Soon we approach the entrance gates to St Mary's Church, which is older than it looks. The first church here was built in 1111, and the building is locally called the 'church of the four ones' in consequence. Little now remains from this period apart from the south door.

Behind the church, we discover a footpath which leads up onto Hoad Hill, eventually joining a track which leads unerringly round to the Hoad Hill Monument, a structure which offers no surprises, dominating Ulverston to such an extent that there is no way you can enter the town without seeing it.!

The Hoad Hill Monument (sometimes known as the Hoade) looks like a lighthouse but that was not- and never has been, its purpose. It was erected to commemorate the Under-Secretary to the Admiralty, Sir John Barrow, the famous geographer and writer who died in 1848 at the age of 84. Barrow was born in 1764 in a little cottage at Dragley Beck, and was educated at the local grammar school. Barrow was good at maths - at the age of 13 he was selected to assist in a survey of the Conishead Priory Estates, and at 14 he took up an appointment at a Liverpool Iron Works, working as wages clerk. From such humble beginnings he rose to greatness, being Secretary of the Admiralty from 1804 to 1845.

After his death, two committees were formed to erect a monument to his memory. One consisted of various naval dignitaries and the other was a local committee. The proposed monument, designed by A. Trimen, was intended to be a land-locked replica of the Eddystone Lighthouse. Soon a £1000 had been raised for the project, among the list of subscribers being HM Queen Dowager, I K Brunel and Sir Robert Peel. It is interesting to note that Trinity House donated #100 to the scheme, with the strict proviso that the monument be made available for use as a lighthouse if so required.

The site chosen for the monument, on top of Hoad Hill, was originally the site of Ulverston's traditional 5th November bonfire. Ulverston, it seems celebrated the occasion not with a Guy Fawkes, but with the burning in effigy of unpopular local officials, shopkeepers and so on, the 'victims' first being paraded through the streets accompanied by a jeering mob.

The foundation stones of the monument were laid on the 15th of May 1850. Early in the morning the church bells were rung, and the Ulverston town band set up in the market place. By 8 am the band was in full swing and hundreds of people had had already gathered for the day's festivities. At 1 pm a procession, by now several thousand strong, set off up Hoad Hill.

After passing through a succession of flower-bedecked arches, the crowd finally reached the summit of the hill, and a short service was held. In a cavity beneath the foundation stone was buried a bottle containing all the coin denominations of the day and a copy of the Ulverston Advertiser. Then the stone was finally laid amidst loud cheers. This was followed by prayers, more cheers and numerous speeches, before the crowds, now numbering about 8,000, wound their way back down to partake of the numerous specially-prepared meals waiting for them in Ulverston! It was, it seems, rather a hectic day for the little town.

The monument was completed by the end of 1850. The final cost was £1,250. Once more bells tolled, flags waved and the workmen were feasted in the tower. All that remained was to erect the lightning conductor, but this was put off to be done at a later date, and the scaffolding was taken down.

Such a blatant disregard of Murphy's Law was asking for trouble, and sure enough, on the 30th of January 1851 just twenty seven days after completion, a freak storm blew up and lightning seriously damaged the monument. Nine massive blocks cut loose, four of them falling outside and damaging the buttresses, the rest falling into the tower smashing six iron girders, two landings, and numerous steps. The top cupola, it transpired, had moved, and consequently the whole upper part of the tower had to be rebuilt, at a cost of #136. During this restoration James Riley, a waller, fell from a broken step into the central well and was seriously injured.

So the monument was completed once more (this time with its lightning conductor), but it was not long left unmolested, for by July of that same year there were reports of vandalism. To rectify this problem a door was fitted to the 100 foot tower and a charge made to ascend the 122 steps and to enjoy the view with the high powered telescope especially installed for the purpose. There were originally three keys to the monument, one held by the Barrow family, one by the tenant of the land and the other by the town trustees. Nowadays the tower is open to the public when the flag is raised.

But you don't need the tower to enjoy the prospect, which southwards looks across Morecambe Bay to Heysham, and northwards to the Lakeland mountains. Ingleborough can be seen, and there are sweeping views across the Leven and Crake estuaries. Nearer at hand is Ulverston, and a fine view down the coast to Chapel Island and to Conishead Priory surrounded by its trees. From Hoad Hill you can plan out the rest of the walk before you undertake it.

From Hoad Hill, a steep, rocky descent leads down to the road and the canal, which we follow for its full length down to the bay at Canal Foot. In summer the 1© miles stroll along the bank is a long, leafy corridor, seemingly stretching to infinity.

The Ulverston Canal was essentially a ship canal - Ulverston's link with the sea. Built in 1795 by John Rennie, it was in its heyday the shortest, straightest and deepest canal in England. Through the sea lock at Canal Foot was shipped Ulverston's iron ore and manufactured goods, creating a golden age of prosperity which made Ulverston the premier port in Furness. The Railway Age and the development of the great docks at Barrow forced the Ulverston Canal into a tranquil retirement. Today the canal is left alone with its memories.

From Canal Foot, the 'oversands' footpath leads across Cartmel Sands to Flookburgh. This is not a walk to be undertaken without a guide. The tide is usually out, but when it does come in, it does so with amazing speed! Swift, treacherous and grey, the waters of Morecambe Bay are not to be trifled with! Lives have been lost hereabouts, and if you happen to be here around high tide, it is not difficult to see why.

Leaving Canal Foot with its pub (the Bay Horse), picnic sites and jetty, our route follows the lane round to Sandside; and then beyond Saltcotes Farm we take to a route which leads back towards the sands, eventually joining a footpath which runs along the coast towards Bardsea. The small island offshore is Chapel Island, which once served as a refuge for travellers crossing the sands. Its mediaeval chapel was converted into a sham ruined eyecatcher by Colonel Bradyll of Conishead Priory (of whom more shortly). A vicious storm turned it into a real ruin in 1984.

From the beach we follow a well defined and pleasant woodland path into the grounds of Conishead Priory. The whole estate is private, but both house and grounds are open to the public, who are encouraged to roam at will. Various exotic trees are to be found in the grounds, and the American Garden includes an atlas cedar and a giant redwood. There is a nature trail and seventy acres of woods and gardens.

Conishead Priory is an architectural work of art or a 'gothick' monstrosity - it depends on your point of view. Certainly it is stunning - worthy of being dubbed a folly in its own right. It was built for Colonel T R Gale Bradyll of the Coldstream Guards by Philip Wyatt at a cost of £140,000, and took fifteen years to build from 1821 to 1836.The project was so expensive that Bradyll had to sell the estate to cover the bill. The end result of all this labour was one of the most outstanding examples of the Gothic revival in Britain. Its turrets are 100 feet high and it contains a gloomy cloister corridor 170 feet long. Colonel Braddyl did not stop here, however. He filled his house with art treasures - Rembrandts and Titians hung from every wall.

Of course this was not the first building on the site. The original priory was a foundation of Black (Augustinian) Canons who had succeeded to a small community originally founded as a leper hospital by Gamel De Pennington around 1160. Besides ministering to the poor and the needy, the canons also maintained a guide to lead travellers over the sands, and it was they who built the chapel on Chapel Island. Conishead Priory must have been a very small foundation, for at the Dissolution its lead, bells and timber were all sold for less than £400. Thereafter it became a private residence, the last of a sereies of houses being demolished in 1821 to make way for the Colonel Bradyll's fantastic creation.

The present priory has had rather a chequered career. Colonel Bradyll went bankrupt twelve years after its completion, and at one stage it was used as a hydropathic hotel. In 1929 it was sold to the Coal Board and the Durham Miner's Welfare Committee for £35,000. They converted the house into a convalescent home at a further cost of £22,000. In 1972 the miners left, and the priory was bought by a Preston entrepreneur who sought to convert the house and grounds into a motel and a site for 300 caravans. Not surprisingly, planning permission was refused, and the house was left empty for five years, during which time it became dilapidated, much of the fabric being attacked by dry rot. Demolition suddenly became an option.

Yet mercifully Conishead Priory has since aquired a new lease of life - as a Tibetan Buddhist community. In 1976 it was purchased by the Manjushri Institute, who have done much towards restoring the house to its former glory. Today, the first thing that greets you as you enter its portals is an enormous statue of Buddha, colourful and serene. The priory is now a college and a community, given over to a very alternative lifestyle. Here there is peace, meditation, tranquility - and self-reliance. History has come full circle and one feels that the Black Canons would almost certainly have approved. Conishead Priory is a 'priory' once more.

While Colonel Bradyll was having his house built, he amused himself by building lesser follies. We have already mentioned the eyecatcher on Chapel Island, and nearby on Hermitage Hill he built a tower, octagonal and machicolated, with a turret and cross-shaped arrow slits. This tower is now owned by Mr Roger Fisher, a local racehorse trainer, who seems intent on making his domains as exclusively private as possible - yet it is to his credit that rather than demolishing Bradyll's tower he is actually engaged in restoring it.

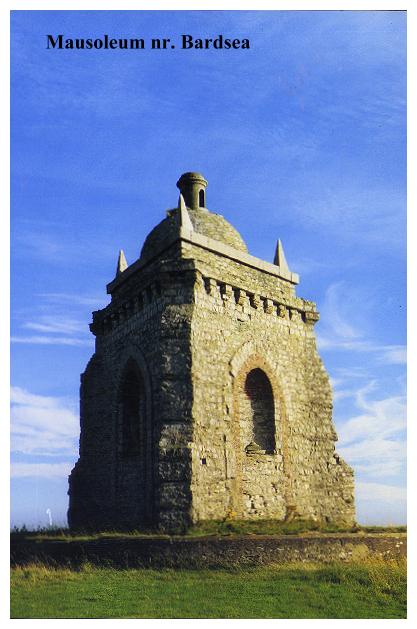

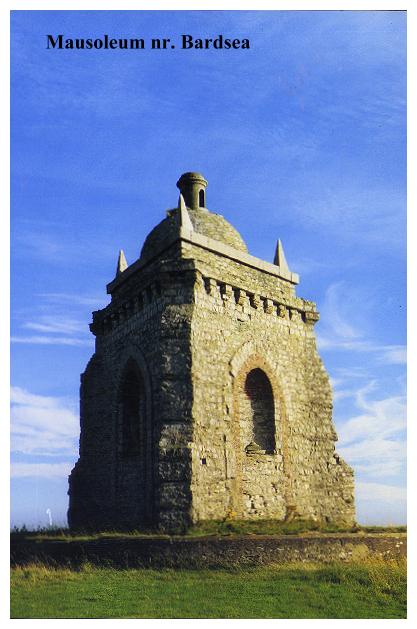

And so we proceed on towards Bardsea and the final folly on our journey, a triangular Mausoleum standing on a high limestone pavement at the top end of Bardsea Golf Club. Permission to inspect may be obtained at the clubhouse, although one suspects that they do not approve of non-golfers walking alongside the fairway. A preferable option is to approach the folly from the Bardsea side, which avoids the golf course altogether and simply entails passing through a field gate and ascending to the Mausoleum along the top of a low limestone scar. After inspection it is a simple matter to retrace your steps to the lane below. I must stress, however, that neither approach is a right of way, for the folly is on private land and you visit it at your own risk. If in doubt, simply stick to the the main route and look at it from a safe distance.

The Mausoleum is certainly worth the detour though. It is a folly in the classic 18th century style - triangular with corner buttresses, corbels, corner pyramids and a central cupola. It contains three niches, one of which contains a sepulchral urn. According to the National Trust book of follies, it was the last of Colonel Bradyll's 'conceits', his last resting place, a building descended from the wild Irish follies of the eighteenth century, in the manner of Thomas Wright's Tollymore follies. Here is a mystery. On one side of this triangular building is an urn with a weathered, almost unreadable inscription, yet enough of it is legible to betray a definite eighteenth century date. But Bradyll was building in the mid nineteenth century. Could this mausoleum have been the creation of the preceding generation of Bradylls? Unfortunately I have not been able to aquire any detailed information about this intriguing and mysterious structure, so who actually built it, must, for the time being at least, remain a mystery.

After a pleasant footpath through woods, our route joins the lane back to Ulverston, and on reaching the outer suburbs of the town we are faced with a tiring tarmac slog back to the start of the walk. If time (and energy!) permit you can make an interesting diversion to Swarthmoor Hall, one of the earliest shrines of Quakerism. The house was the abode of Judge Fell, a friend of George Fox, and Fox stayed at Swarthmoor in the 1650s. Today the house is owned by the Society of Friends and it is open for public inspection.

So we come to the end of what has been a long, but highly interesting perambulation. Sea and sands, crags and mountain vistas, not to mention an interesting little town, have all featured in our journey. A long walk- but well worth the effort...