THE BEACONS WAY

SECTION 1.

Whalley to Blacko

"Our food is scanty, our garments rough; our drink is from the stream and our sleep often upon our book. Under our tired limbs there is but a hard mat; when sleep is sweetest we must rise at a bell's bidding. Everywhere peace, everywhere serenity and a marvellous freedom from the tumult of the world."

AILRED OF RIEVAULX - The Mirror of Charity.

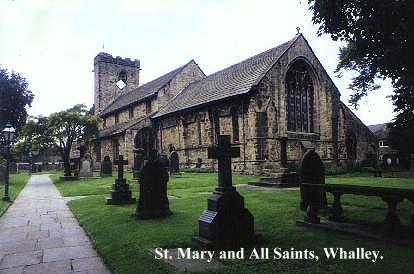

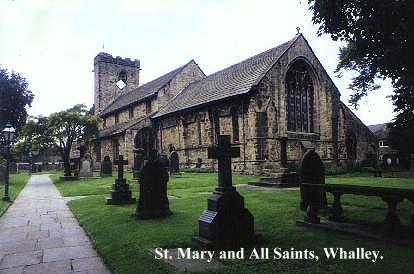

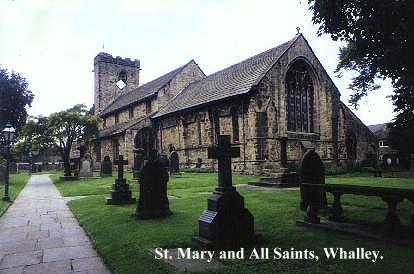

Whalley dreams! A backwater-ish kind of town, its Town Gate is its hub, bustling, yet spared the really heavy traffic which thunders at a distance to the north and east. Obscure, yet possessed of a noticeable vitality, Whalley has a modern facade which neither betrays nor disturbs the slumbers of its rich antiquity. Step off its main street, following the pathway which runs across the green sward of St. Mary's Churchyard and you can travel back in time, to the beginnings of a story and the start of a journey.

And what better place to start a journey?? Whalley is situated on the northern bank of the Lancashire Calder, slightly to the south east of where it flows into the Ribble. Southwards, Whalley is dominated by its tree capped Nab, but in the context of this work our attention is drawn towards the east, where rises Wiswell Moor, the most westerly bastion of the long ridge which culminates in the 'Big End' of Pendle Hill, our first 'beacon' and ultimate destination.

Whalley is best known for its Abbey, and one might be forgiven for thinking that Whalley's story starts there, but this is not the case. To find Whalley's beginnings we must in fact travel much further back in time, to a wild landscape from which the legions of Rome had not long ago departed. A mere few miles to the west the gaunt ruins of their fortress at Ribchester (Bremetenacum) still formed the hub of a network of decaying military roads which would still have been in use on that fateful day, when an itinerant priest first sought to bring the word of God to what then would have been little more than primitive huts in a remote forest clearing.

The name of this determined priest was Paulinus, and his mission was to bring Christianity to the fierce and pagan peoples of Northumbria. He had started with the King. About the year 625, Edwin the Great married Ethelburga, sister to the king of Kent, the second most powerful king in Britain. Ethelburga was a zealous Christian, and would not consent to marry Edwin unless she was allowed to exercise her religion without disturbance. Edwin, a pagan, reluctantly agreed. Among the new queen's retinue was Paulinus, who had been consecrated as Bishop to the (then) non-existent See of York by Justus, Archbishop of Canterbury. Edwin at first refused to embrace Christianity, but on Easter Eve 646 his queen bore him a daughter, and so moved was he at Paulinus' great and sincere joy at the news of the queen's happy delivery, that he consented to the baptism of the child, and in the following year he himself embraced the Christian religion, being baptised in a hastily constructed wooden church on the site of what is now York Minster. Thus began the conversion of Northern England to Christianity.

And so Paulinus and his later followers came to Whalley, and where they preached were erected Whalley's oldest monuments, the three dark age crosses that stand in what is now the churchyard. Experts argue as to the exact date of the crosses, some authorities dating them to the 10th century A.D. Some suggest that they are, in fact, celtic crosses, erected by a Scottish mission from Iona. Tradition, however, asserts that Paulinus preached here, and tradition (which often has a habit of proving experts wrong!) is good enough for me, and more appealing!

Christianity replaced paganism, but it did not (or more likely could not) eradicate many of the pagan practices it encountered. Old ways die hard, and centuries afterwards the Church would still be permeated with traditions, art, saints and festivals, many of which owed their origins to pre- christian practices and beliefs. Even after the Reformation, backward, rural Lancashire still stuck obstinately to Roman Catholicism and the 'Old Faith'; perhaps it was the fragmented survival of an even older faith which brought that sad group of women known as the 'Pendle Witches' to their doom on the gallows of Lancaster Moor in 1612.

Local tradition asserts that anyone who can decipher the 'hieroglyphics' on the largest of Whalley's three crosses will learn the secret of invisibility. The 'hieroglyphics' however,, are not so much a form of writing as the forceful, convoluted and vigorous rings, lozenges and spirals so typical of dark age celtic and viking art. They echo a psychic world peopled with dragons, serpents, atavistic impulses and elemental forces. The cross within the wheel, the symbol of Christ's love, is the unifying factor which holds them in place - the holy cork that keeps the pagan genies 'in the bottle.' The rings, lozenges and spirals have a deep psychic significance of far greater antiquity than even these ancient crosses, as we shall see. (This very boldly carved cross also represents the 'Tree of Calvary' another symbol which has a deep rooted pre-christian significance, and which we will be exploring elsewhere on our journey).

In the wake of Whalley's crosses came its church. According to tradition it was originally wooden, and known as the 'White Church under the Hill'. Certainly by 1086 the authors of Domesday could write "The Church of St. Mary had in Wallei two carucates of land free of all custom", (a carucate being the amount of land that a team of oxen could plough in a year - usually about 120 acres.) Certainly by the time of the Conquest Whalley had been long established as a centre of christian worship.

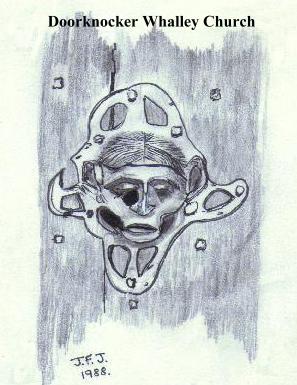

About 1080 what was probably the first stone church on the site was constructed, some of the stone being looted from a roman building, or perhaps from nearby Ribchester. (Part of the arch over the north door of the church, for example, is inscribed 'Flavius', and a stone at the western end of the north aisle is carved with a relief of the god Mars, and was probably part of a roman altar.) This first stone church did not last long, and was probably destroyed by fire, the building of the present church being begun around 1200.

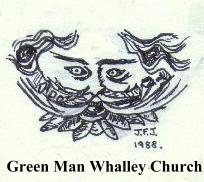

To go into the subsequent history of this lovely church is beyond the scope of this work. Suffice it to say it is a treasure house worthy of leisurely exploration. I was particularly struck by its magnificent choir stalls, carved about 1430 and brought from the nearby Abbey after its dissolution in the reign of Henry VIII. The misericords (the undersides of the seats) are beautifully carved, and evoke all the vibrance and superstition of the Middle Ages. They include a dragon, a man shoe-ing a goose, a swine beneath an oak tree, a soldier being beaten by his wife with a frying pan, a weeping satyr, a fox stealing a goose, St. george and the Dragon and perhaps most significantly of all, a 'green man' with boughs issuing from his mouth. (He also appears in the carved arches above the stalls). If Whalley ever possessed a pagan deity, he would surely have been it. Green George, Jack-in-the-Green, the May King, patron of fertility and forest, remnant of ancient rituals which at one time almost certainly involved human sacrifice. In the Middle Ages he would be transformed into a symbol of the struggle of Anglo Saxon England against the yoke of Norman tyranny - the Man in Lincoln Green, Robin Hood. Then, much, much laster 'Green George' would appear yet again, this time inj the guise of 'General Ludd' mythical leader of Luddite machine breakers! Thus as the Celts had their King Arthur to personify the aspirations of their race, so the English had their Robin Hood - their 'Green Man'.

From the choir stalls of Whalley Church we move to their point of origin. Whalley Abbey is approached through its magnificenr mediaeval gatehouse, where a flag with three fishes, (the Abbey's emblem) flutters gaily in the breeze, alongside the Union Flag. Whalley Abbey has a curious history. Its roots lay with the Cistercian Abbey of Stanlaw, near modern Ellesmere Port, which lay on a point jutting out into the River Mersey and had been founded in 1186. This abbey was frequently flooded by the river, and this, combined with their church tower having been struck by lightning and the abbey near destroyed by a disastrous fire, spurred the monks into searching for premises elsewhere. Thanks to the generosity of Henry De Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, (whose ancestor, John, had originally endowed the Stanlaw foundation) the monks had been granted lands in the Whalley area, so in 1283 they applied for Papal and Royal permission to move here and establish a new abbey.

So it transpired that in 1288 an 'advance guard' of six monks arrived in Whalley. But why Whalley? The choice of site seems inconsistent with a monastic order whose general practice was to establish their abbeys in the wildest and remotest places they could find, far from the habitations of men; for in this singular respect the choice of Whalley was quite unsuitable. Not only did Whalley already possess a long established, existing church, with its attendant village community, it also lay within the sphere of influence of nearby Sawley Abbey, 7 miles to the NE; and it seems likely that both the Abbot and monks of Sawley, and the then Rector of Whalley, Peter De Cestria, both resented the prescence of these upstarts from Merseyside! Perhaps it was due to local difficulties caused by these parties that the foundation stone of Whalley Abbey was not laid until 1308. (By Henry De Lacy.)

Arms of Whalley Abbey

Altogether the great abbey took 127 years to construct and a mere 92 years after its completion came the Dissolution! As Cistercian Abbeys go Whalley was a bit of a latecomer, and this perhaps explains the uncharacteristic lavishness which went into its construction. (The Cistercian Rule had become somewhat lax since the Days of St Bernard and Ailred of Rievaulx). Certainly no expense was spared - french masons and italian woodcarvers were hired, and, as the choir stalls now in the church so amply demonstrate, there was a tremendous ostentatiousness, quite out of place in an order whose rule had always been no carvings or images and a life of harsh austerity! And Whalley Abbey not only looked well..... it lived well. The last Abbot of Whalley, John Paslew (of that family who once dwelt at East Riddlesden Hall near Keighley), spent £500 out of the abbey's £900 income on food - raisins, figs, dates, sugar, currants,cinnamon,almonds, nutmeg, ginger, liquorice and cloves; not to mention wine and large quantities of meat! The Abbot and his guests lived in lordly style - a style fated to quite suddenly disappear with the arrival of the 'tumult of the world' in the form of Henry VIII's Commissioners in 1537.

In 1520 Brother Edmund Howard was reputed to have appeared after his death to Abbot Paslew, warning him of dire events to come. The prophecy came true. In 1536 the Pilgrimage of Grace erupted in the North in protest at Henry's religious reforms and Paslew was unwillingly drawn into the rebellion by William Tempest of Bashall, who forced the Abbot to open his gates with the threat of fire. Paslew's compliance was to cost him dear - the rebellion collapsed, and his implication, along with his refusal to take the oath acknowledging Henry as Head of the Church, resulted in his being hanged, drawn and quartered at Lancaster on 9th March 1537, along with various other brothers from both abbeys in the area. (Tradition would have it that he was hanged in his own doorway, but the evidence does not support this story).

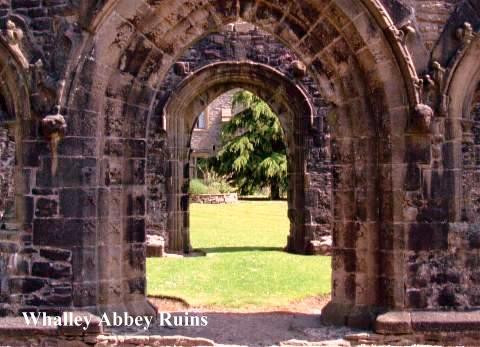

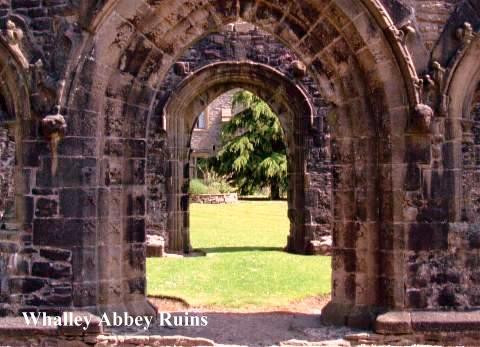

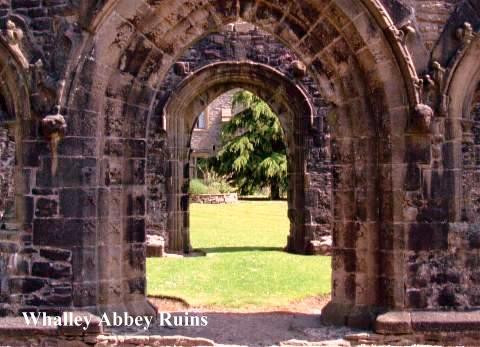

Because St. Mary's Church was available nearby, no attempt was made to spare the abbey church, and the mighty building with its transepts and massive cathedral-like dimensions was levelled to its foundations, which are all that remain today. The rest of the abbey fared better :- both its gatehouses have survived, and part of it was turned into a private house, which became the home of the Assheton family.

The ruins that remain, set in a peaceful garden, are quite impressive. The house is now a Church of England conference centre and retreat, whereas the western part of the cloister, the cellarium and lay brothers dormitory and refectory, are now in the grounds of the Roman Catholic Church of the English Martyrs. Consequently the cloister is cut in two by a modern boundary wall worthy of central Berlin! It is a poignant (and modern) reminder of the differences in belief which originally brought this once magnificent building to its present state of ruin.

Two items caught my interest as I explored the grounds of Whalley Abbey. One of them was the curious pair of rectangular pits to be found in the centre of what was originally the nave. Here stood the choir stalls, now in St. Mary's Church. The pits were originally floored over with oak, and were designed to give greater resonance to the voices of the choir: - a sort of mediaeval public address system! The other item that caught my interest was the cloister, in some respects more the heart of the abbey than the church itself. It was here, in the slype, the passageway that leads to the abbot's lodging, that the Abbot of Kirkstall, on an unofficial visit, was savagely attacked by one of the Whalley monks! Such was the mildness and gentleness of white robed Cistercian brothers! Yet despite these rather odd 'hiccups', life at Whalley must, generally speaking, have been peaceful indeed. In the southeastern corner of the cloister stands the remains of the lavatory, or washing trough. (The meaning of the word has altered - what we call a lavatory, they refered to as a rere-dorter or garde-robe). The trough is surmounted by a stone canopy adorned with a fylfot or swastika, a curiously pagan emblem for a christian monastery. Why? I thought. A study of the Cistercian Rule seems to provide the answer. The swastika is the ancient indo-aryan sun wheel, and the monks of Whalley lived their lives by the sun. At sunset they retired to the dormitory until the hour of midnight, at which time, ('when sleep was sweetest') they were summoned to service in the church. The service over, they then filed into the cloister, where time was spent in prayer and reflection until sunrise, when the monks proceeded to the refectory and had breakfast, (ie 'broke their fast'), first washing themselves at this trough as the first light of dawn fell on the carved sun wheel above their heads!

From the Abbey we retrace our steps back through the churchyard to Whalley Town Gate, and the start of our jouney. There is an abundance of inns hereabouts, each of them offering some interest. The Whalley Arms was built with stone from another building:- Portfield Hall, and, along with its neighbours, the Swan and the Dog it had, until the late 19th century, a farm attached to it. The Swan was the coaching inn, staging post for the 'Manchester Mail', and the De Lacy Arms, formerly the Shoulder of Mutton, is built on the site of Whalley's ancient manor house.

The start of our journey seems unpromising. Traffic lights, busy roads, streetlamps and tarmac are all in evidence until we arrive at the main Clitheroe-Blackburn Road, about a half mile to the east. Crossing it is potentially lethal, yet beyond it picnic tables, a car park and nature trails are in evidence, all of which tend to seduce you from 'the true path' which actually runs up the edge of the golf course, beyond a field gate.Now the first stage of ascent starts, and soon we arrive at Clerk Hill, where the view starts to open up. Here, according to the stained glass in the church below, lived the Whalley Family of Clerk Hill. Beyond it is perhaps the oldest of all the sites in the area, once designated as a roman fort, but more likely an older, British, stronghold, as bronze age implements and jewellery have been unearthed here by archaeological excavations.

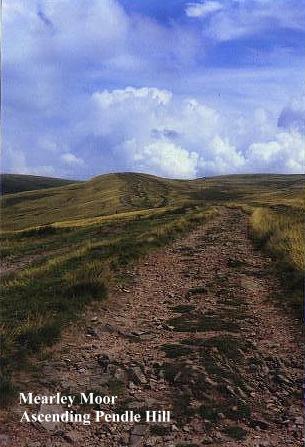

From Clerk Hill the route ascends gradually and unerringly to the old road leading up to the Nick of Pendle from Sabden. Ascending to the 'Nick' we enter the realms of packhorse men and drovers, for this is a route of great antiquity. An old 'Long Causeway', it winds its way through the narrow pass on its way over to Clitheroe. It has been suggested that Pendle's 'Nick', visible on the skyline for miles around, was possibly an ancient 'siting cutting' for prehistoric travellers, and as such it would fit in well with the general rules of identification for those contentious prehistoric 'Old Straight Tracks' or 'Ley Lines', a controversial subject we will be discussing later.

Beyond the Nick the view across the Ribble Valley opens up, with Clitheroe Castle in view, flag flying upon its rocky knoll. Our route stays on the ridge, but if the weather is hot it is well worth the short descent and return climb to enjoy the hospitality of the nearby Well Springs Inn. (You could even go ski-ing on the adjacent slope if you can raise the energy!) The Well Springs has an antiquity greater than its appearance might suggest - once upon a time, it was a wild, rough, moorland pub - a haunt of packhorse men, chapmen, drovers and farmers en route to market. Those days have long passed, and if you visit the inn now you are more likely to encounter the car borne 'pub poser' or the itinerant sales rep.!

Having slaked your thirst, and ascended the road back to the head of the pass, the route continues along a well defined footpath along the crest of an ascending ridge. This is a popular spot for kite flyers and hang gliders, and, on reaching a post and cairn on a high knoll, the view really begins to open up, taking in, (if the weather be clear), the Ribble Estuary and Blackpool Tower. Most prominent of all is Clitheroe, framed in the immediate foreground against the wild backdrop of Longridge and the Bowland Fells. Clitheroe is an interesting town - its Norman keep is one of the smallest in the country, not to mention one of the oldest, and it is well worth a visit, although you are unlikely to get a chance whilest on the Beacons Way.

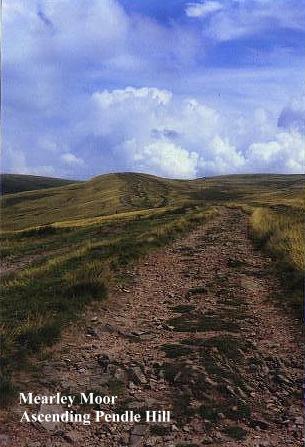

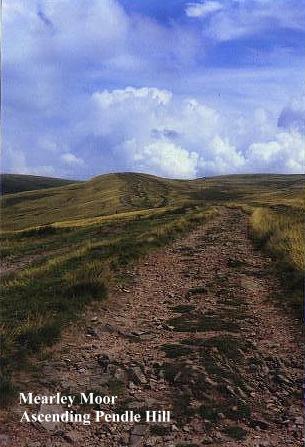

Leaving the 'beaten track' behind, the Beacons Way heads towards Ogden Clough, beyond which lie the western flanks of Pendle itself. The route is cairned and well defined, and follows the left bank of the stream. It did not seem so well defined, however, when I first came this way around 1973, plodding dejectedly through a landscape belaboured with mist and drizzle. The path, so obvious near the Nick, gradually petered out into nothing and I found myself scrambling down into Ogden Clough, becoming gradually more perplexed as to which way I should go. After scrambling out of the other side of the ravine I soon found a nightmare landscape of trackless moorland, bog holes and peat hags. As there was only a few yards visibility I set my compass on the silhouette of a large boulder lying in what I assumed to be the general direction of Pendle Beacon. I plodded on, the boulder never seeming to get any closer, and worse still, I also seemed to be moving off my bearing. Then a break in the fog suddenly revealed all as the rocky silhouette moved off:- it was a sheep! I returned to the true bearing,, and after a slog through mud and drizzle I finally espied the summit, with three figures huddled around the trig. point. Mercifully they weren't three 'secret, black and midnight hags' hovering through the 'fog and filthy air'. They turned out to be three students from Liverpool!

If, unlike me, you stick to the cairned path which now follows a clearly defined route up the left side of Ogden Clough, you should have (apart from a wet bit on the moor) little difficulty in reaching the summit of Pendle, the first and most impressive beacon to be encountered on our journey.

PENDLE BEACON or BIG END, has a character all its own. Greater than a hill, lesser than a mountain, its only affinity seems to be with distant Ingleborough and Penyghent over in the Craven Dales. One feels that Pendle secretly wanted to be one of the 'Three Peaks', but never quite made it, its rightful place being usurped by an upstart Whernside. Pendle, dark and whalebacked, broods lonely and aloof, a creature set apart simply because it has the misfortune to be over the border in Lancashire! It seems so out of place:- it dominates its neighbouring hills, but has little similarity or affinity with any of them, belonging neither to the Pennines nor the Bowland Fells. Pendle stands alone, distinctive and unique.

But it takes a Yorkshireman weaned on Ingleborough and the Dales to be derisive. No Lancastrian would dare to speak ill of his counties' most famous eminence! All around, and especially to the south, it dominates the local landscape, the industrial conurbations of Burnley, Nelson and Colne dwelling virtually in its shadow. Hills abound everywhere, but to Lancashire folk Pendle is THE Hill,

And so it is - its name is derived from the celtic 'pen', meaning 'hill', and when the english came they added their name for 'hill' to it, and latterly, in historical times, it has acquired the hardly outstanding designation of 'Hill'. Thus Pendle is a hill in triplicate!!

Pendle Beacon towers 1,831 feet above sea level and its wild ridge is almost seven miles long, covering an area of some 25 square miles. The views from its summit, if the weather is clear, are fantastic - the Three Peaks, the Dales, The Lake District, the Pennines, Longridge, the Bowland Fells, the Ribble estuary, Blackpool Tower and even the mountains iof North Wales are all in view. In fine weather Pendle receives a constant stream of visitors, the more intrepid making the gruelling ascent from Barley. (A party of Asians were on the summit when I last visited it).

Visitors to Pendle Hill are not a new phenomenon:- many people have passed this way down the centuries and some of them have left their impressions.

"Penigent,Pendle Hill, Ingleborough,

Three such hills be not all England through,

I long to climb up Pendle, Pendle stands,

Rownd cop, survaying all ye wilde moorelands..."

Thus wrote Richard James in 1636 (dutifully acknowledging Pendle's rightful place in 'society'!) At this time the hill was still very much in the news, it being only three years after the second Pendle witch trial. Sixteen years later, an even more memorable traveller was to visit Pendle, in the form of George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends, (dubbed 'Quakers' by the malicious Judge Bennett). Fox climbed Pendle Hill and records in his journal of 1652 that:-

".......as we travelled on we came near to a very great and high hill, called Pendle Hill, and I was moved of the Lord to go to the top of it, which I did with much ado, as it was so very steep and high. When I was come to the top of this hill I saw the sea bordering upon Lancashire; and from the top of this hill the Lord let me see in what places he had (caused?) a great people to be gathered. As I went down I found a spring of water in the side of the hill, with which I refreshed myself, having eaten or drunk but little in several days before."

In the wake of Fox came other illustrious travellers. In 1725 Stukeley described Pendle as "a vast black mountain which is the morning weather glass of all the country people"; and in the same century Defoe, (author of 'Robinson Crusoe') wrote that Pendle was "monstrous high", in a landscape "all mountains and so full of innumerable high hills that it was not easy for a traveller to judge which was the highest."

It was the 19th century, however, which brought the first real 'tourists' - workers and operatives from the mills and factories of industrial Lancashire, people enjoying that characteristically victorian institution of 'the day out'. The recreations and amusements would usually begin on the first Sunday in May, when vast numbers of townsfolk would congregate on Pendle to participate in 'Nick o' Thung's' Charity, a supposedly ancient custom revived (but more likely invented) in 1854, being the inspiration of one Tom Robinson, a local 'character' known to one and all as 'American Tom'.. The revellers would usually set off from Pendle End Bridge, and each male member of the various groups had to be able to show a half crown, an ounce of tobacco and a box of matches before setting out. Camp fires were lit, and nettle pudding prepared, with eggs, meat and dripping. Subsequently a 'reet good do' was had by all.

Such diversions and recreations continued right through the 19th century, no doubt reaching a high point in June 1887, when a beacon was lit to celebrate Queen Victoria's Jubilee. Stone pillars and railway lines were supplied by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to build a beacon platform on the summit of Pendle. When completed, the great pyre was thirty feet square and thirty five feet high, and contained 17 tons of coal, three barrels of petrol, a ton of naptha and many hundreds of tar barrels and other inflammable materials. On the appointed day (Jubilee Tuesday), great crowds gathered on Pendle to see the blaze. By 9 pm there were over a thousand people on the hill, scanning the surrounding hills for a signal. At 9.30 one of the Yorkshire beacons could be seen ablaze, and others soon followed. Then, (after three rousing cheers for the Queen), the beacon was fired by a Mr. Massey and fifty years of Victoria's reign was duly celebrated in style by the assembled masses.

From Pendle Summit our route descends to Barley (although you can miss it out if you want - see map). To say that the path leads DOWNHILL is something of an understatement, dor it descends with a capital 'D' right down the face of Pendle's 'Big End'. The way is hard and steep, and your legs will ache, but don't be downhearted - you could be walking the opposite way! The path here has been badly eroded by the endless stream of visitors, and had (at time of writing) been recently repaired by a countryside management team, who had resorted to the unusual method of ramming stone slivers 'end on' into a wooden framework, thus creating 'cobbled steps'. They have also provided a series of seats for those gasping unfortunates you see stumbling towards you, braving coronary failure for the sake of a view of Blackpool Tower! At the bottom of 'the stairs' waymarks for 'The Pendle Way' are encountered, and the route descends through pastures green down towards Barley.

Barley is a rambling little village. In 1324 it was known as 'Barelegh' (ie. Infertile pasture.) Today it is green and lush, but long ago it would have been little more than a wild and lonely outpost of the ancient 'Forest of Pendle', a mediaeval hunting reserve where deer, wolves and wild boar roamed free even as late asw the 17th century. At a local court in 1537 John and Randle Smith were fined for keeping dogs for hunting wild animals within the 'Chace of Pendle' contrary to statute, and without licence. (In Norman times they probably would have been hanged!)

The whole district (if you hadn't already noticed), is dominated by the 'Big End' of Pendle. Barley is 'back o' Pendle' and lies beneath the 'shady side' of the great hill. Pendle influences the weather and subsequently the agricultural calendar hereabouts. Occasionally, heavy rainfall causes sudden and devastating spates of water to burst forth from the hillside causing great damage to the villages below. (Notable floods are reputed to have occurred in 1580,1669 and 1870). An old rhyme sums up the relevance of Pendle to local husbandry:-

"When Pendle wears a woolly cap

the farmers all may take a nap

when Pendle Hill doth wear a hood

be sure the day will not be good...."

Under less dramatic conditions farm workers used to see Pendle's bold evening shadow as a kind of 'sundial'. When the shadow when the shadow reached a place where two walls came to a point the haymakers in the meadows knew it was five o'clock and time for tea! In such ways, for 'fair or foul' did Pendle decide the destiny of the area lying beneath its brooding flanks. And it still does.

Barley was noted for cattle breeding as far back as the thirteenth century, and was (as it still is) a predominantly farming community. The Industrial Revolution, which completely urbanised Barley's neighbouring valley, did not leave Pendleside unscathed, however, and in the eighteeth century textiles began to be manufactured as many local inhabitants turned to handloom weaving to supplement their meagre incomes. Around 1800 Narrowgates Mill was built for cotton spinning by one William Hartley, surviving as late as 1967 before being turned into private housing; and to the south west of the village stood Barley Green Mill, which in its prime had 200 looms before it was destroyed by a great flood in 1880. (Its owner, George Moorhouse, was fined £58 for running the mill five minutes beyond the legal limit).

From Barley the Beacons Way follows the track up to the Blackmoss Reservoirs. Completed in 1894, Upper Black Moss is oldest, and has a capacity of around 45 million gallons. Lower Black Moss was completed in 1903 and holds 65 million gallons. Both reservoirs were built to answer the drinking water needs of a rapidly expanding Nelson, and large gangs of 'navvies' were employed in their construction. The 17th century barn in Barley known as Wilkinson Farm, which stands not far from Barley Post Office, was used as a chapel for the navvies, who were for the most part Irish and Roman Catholic. Later, during the construction of the Ogden Reservoirs, it is recorded that groups of navvies would often walk over to Nelson to attend Mass. These men, when they were there, almost doubled the population of the area and there must, for a while at least, have been some rip roaring 'stirrings'in normally peaceful Barley!!

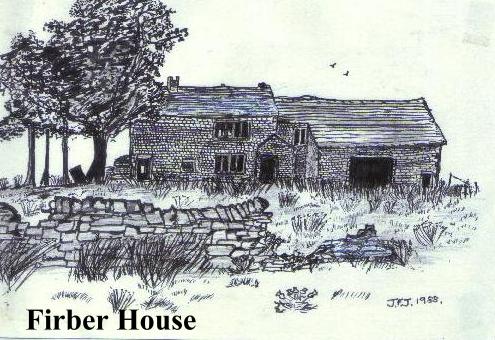

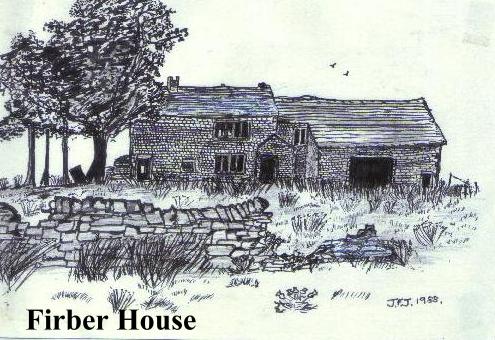

Beyond the reservoirs the route leads out to Firber House, Via Mountain Farm. At Mountain Farm the path becomes indistinct, and before passing through the gate to the right of the farm, I asked the farmer if I was heading in the right direction. "Firber House?" he said, "Oh yes- just go straight on up the pasture". He gave me a strange look, as if he knew something I did not. It was the look of one not used to directing walkers there. Amid thistles and tumbled wall I discovered why:- Firber House is derelict, a long, traditional farmhouse with sightless eyes and rotting rafters - a shelter for sheep. Sad in a way. The fabric is in decent condition and it would not take too much money to make it into a fine house. (Farms have been renovated in the South Pennines from far less, often no more than a pile of stones.) The reason for its dreliction is, I suspect its remoteness and lack of vehicular access; so Firber House stands condemned to dust and oblivion - the archetype of a song I once wrote:-

"The wind blows cold at Jack o' Johnnies'

The roof is down, the hearth is bare,

There's only the mist and wind and rain,

To tell of the man who once lived there......

But what a location! Eat your heart out Wuthering Heights! To the west the great whaleback of Pendle broods ominously and Firber House, lost in its thistles and desolation broods also, dominated by the massive bulk of Pendle's 'Big End'. Here, nothing else seems to exist:- Firber House has Pendle to itself and together they exist in a wild upland almost devoid of human habitation. Down in Barley the landscape seems softer, but here it is nature in the raw! If, in your travels through the 'witch country' you sought the company of 'secret, black and midnight hags', here is the one place you might find them - sitting around their cauldron and hiding from the tourists! Firber House is a place to rest awhile, and to be alone with your thoughts. We have said much about the Pendle region, but so far I have deliberately avoided discussing what today seems to be the area's main tourist attraction:- the "Pendle Witches". Now I have lured you into my lair, however, let me weave the spell..........

It is not for me to pursue the story of the Pendle Witches in minute detail. Accounts abound, and anyone wishing to delve more deeply into the subject need not search far to find a wealth of material. We are but travellers passing through, so I'll relate the story and then, rather than bore you with tomes of history I will offer you a few thoughts and opinions of my own, which you may (or may not) find to be of value.

Our story begins at the end of the sixteenth century. In December 1595 Christopher Nutter and his sons, Robert and John, were travelling home through Pendle Forest when John Nutter suddenly felt ill. He told his father that he thought he had been bewitched by 'Chattox', whose family he was seeking to evict from his land, and who doubtless harboured a grudge against him. 'Chattox' was an old woman of about seventy, whose real name was Anne Whittle. She lived with her daughter, also called Anne and her son-in-law Thomas Redfearn and their family.

Not long afterwards, en route for Chester, John Nutter threatened to evict Redfearn on his return. He never did:- he died on the way back, and shortly afterwards his father, Christopher Nutter, took to his bed and also died, convinced that he had been bewitched.

Thus it was that Anne Whittle was given her unsavoury reputation. Senile and decrepit, she would walk about constantly muttering to herself; hence the nickname 'Chattox'.

Yet old Chattox was but one character in the cast of this tragic melodrama. Not very far away, at a place called Malkin Tower, dwelt her arch rival - Old Mother Demdike. Her real name was Elizabeth Southernes and she, (like Chattox) lived with her daughter and son-in-law, Elizabeth and John Device and their family. In the early years of the seventeenth century Malkin Tower was burgled and shortly afterwards one of Chattox's daughters was seen in possession of a cap identical to one which had been stolen. The Demdike 'clan' seemed to fear the Chattoxes and paid them an 'aghendole' (8lb) of oatmeal every year as a sort of 'protection money'! One year, however, John Device decided not to pay it, and not long afterwards he too died, convinced that Chattox had bewitched him.

Not that the Demdike 'clan' was any better. John Device's daughter, Alizon, and her grandmother had gone to Baldwin's Mill at Wheathead to ask extra payment for some work she had done. Baldwin ordered them off his land, calling them 'whores and witches'. A year later the miller's daughter took sick and died. On Wednesday 18th March 1612 Alizon Device, on her way to Trawden to beg, met one John Law, a pedlar from Halifax and asked him for some pins from his pack. He refused to unpack and the pair argued, whereupon Law collapsed with a stroke that struck him dumb and paralysed his left side. He, like the others, blamed his ills on witchcraft and wrote to his son Abraham in Halifax to come and help him.

Amazingly, Alizon confessed to Law and his son that she had bewitched the old man, and begged his forgiveness, whereupon the pedlar recovered his speech. Unfortunately Alizon's real or imagined guilt proved to be her undoing, as the son was uninclined to let the matter drop, and complained to Roger Nowell, the Magistrate of Read, not far from Whalley. This made the matter 'official'- accusations had been made, and Nowell, responsible for upholding the law, was duty bound to act. This was to have fateful consequences for the Chattoxes , Demdikes and a good many more besides.

Nowell's first move was to interview Alizon Device. She admitted to being angry with John Law and told of a black hound which had appeared to her, offering to make the pedlar lame. She had, she said, been initiated into witchcraft by her grandmother some two years before, and the dog was her familiar. Her grandmother, she said, had bewitched a sick cow belonging to John Nutter of Bull Hole Farm after he had asked her to heal it. The charm failed, though, and the cow died. Alizon also told how her grandmother had 'magicked' a 'piggin full of milk' and turned it into butter, and revealed details of the incident with Baldwin the Miller.

By now amazed, Nowell listened intently as Alizon unravelled a whole catalogue of stories which today would simply have been dismissed as the spiteful delusions of a young girl. There was the story of the burglary, and of her father's death because he would not pay for 'protection' to Old Chattox.... And the story of Anne Nutter, who had died two years previously, within three weeks of 'laughing at Old Chattox'....John Moore of Higham had accused Chattox of turning his ale sour, and Alizon had seen the clay image with which Chattox had caused the death of Moore's son by way of revenge. Other accounts followed and Nowell was convinced enough of witchery to detain Alizon and to seek out those she had incriminated.

On 2nd April 1612 Nowell questioned Chattox, Demdike and Anne Redfearn at Fence. As with Alizon Old Demdike freely admitted to witchcraft, claiming that the devil had appeared to her 20 years earlier in the form of a boy named Tib, who could also be a brown dog or a black cat if required! She said that Tib would suck blood from under her left arm, where she had a 'witches' mark'. She explained how she used clay images to work magic, and said that she had seen Chattox and Anne Redfearn making images of Christopher, Robert and Marie Nutter, shortly before Robert's death. Chattox, when questioned, explained that her 'familiar' was a man named 'Fancie' who had tried to bite her arm when she refused to harm the wife of miller Baldwin. She also admitted using witchcraft to take revenge on Robert Nutter, whom she alleged tried to seduce her daughter.

Faced with such damning 'evidence' the guilt of the four women seemed clear to Nowell, and on Saturday 4th April 1612, after a period of detention, Demdike, Chattox, Anne Redfearn and Alizon Device were conducted to Lancaster Castle to await trial.

The news of the arrests soon travelled around the closely knit communities of Pendle Forest, and on a Good Friday, the 10th of April, a large group of friends and relatives of the prisoners convened a meeting at Malkin Tower to decide what should be done next. Word of this meeting also reached Nowell, who sent Henry Hargreaves the Constable to investigate, which resulted in the arrest of still more 'witches'. Elizabeth Device, her son James and her daughter Jennet were taken, and, being only a child of nine years old, little Jennet freely signed the death warrants of her family, revealing how her brother had stolen a sheep to feed the meeting, and how they had planned to blow up Lancaster Castle, murder the gaoler and free the four women!

Once again the 'familiars' and the crumbled clay 'images' appeared, apparently responsible for the deaths of Miss Towneley of Carr Hall, who had accused James Device of stealing turf, and one John Duckworth, who had neglected to give James an old shirt he had promised. Device also revealed how his mother Elizabeth had caused the death of local farmer John Robinson by crumbling a clay image. There could only be one outcome to all of this:- they were sent to join the others in the dungeon of Lancaster Castle.

The 'examinations' continued, as more and more people were implicated. In May, Alice Nutter of Roughlee, John and Jane Bulcock, Alice Gray and Katherine Hewitt were all sent to Lancaster. Of these, Alice Nutter was perhaps the most surprising:- the Chattoxes and Demdikes were little more than beggars, but Alice Nutter was of good breeding, a gentlewoman, literate, well educated and married to a respected local landowner! She was charged with the murder by witchcraft of Henry Mitton of Roughlee, and was arrested on the testimony of the Demdikes, who all maintained that she had been at the meeting at Malkin Tower. She had killed Mitton, it was alleged, because he had refused to give Demdike a penny!

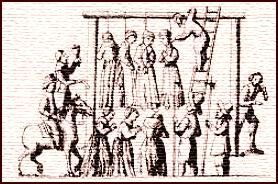

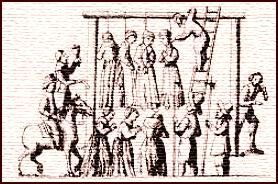

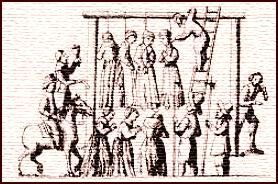

The outcome of the Pendle witch trials was almost a foregone conclusion. Chattox, Elizabeth Device and James Device were all found guilty. On 18th August Anne Redfearn, Chattoxs' daughter, was tried but acquitted. Next, John and Jane Bulcock and the teenaged Alizon Device were brought to trial - all were found guilty as charged. On 19th August Alice Nutter was tried. She was placed in an identity parade, where she was pointed out by little Jennet Device, who said she had been at the Malkin Tower meeting. Alice Nutter said nothing. She neither offered an alibi nor confessed to being a witch. She was found guilty. Other trials followed, and on 20th August 1612 Old Chattox, Anne Redfearn, Elizabeth Device, James Device, Alizon Device, Alice Nutter, Katherine Hewitt, Jane Bulcock, John Bulcock and Isobel Roby were led through the streets of Lancaster to Lancaster Moor, where they were hanged. (Old Demdike was not among them. She had died in the squalor of Lancaster Gaol before being brought to trial).

Thus was the tragic drama of the 'Pendle Witches' brought to its inevitable (but not final) conclusion. The survivors of the trials and their relatives returned to their homes and went back to the day-to-day business of getting on with their lives. That might have been the end of it, but unfortunately reputations had been acquired and people had been 'marked' by these sad events. Families still remained 'under suspicion', and so it transpired that in 1633, when the 1612 witch trials had become little more than a fading memory, the tragic taint of witchcraft once more raised its ugly head in the Forest of Pendle, though happily with less horrendous results.

On All Saints Day, 1632, a boy named Edmund Robinson arrived home late. He had been sent to bring the cows in but had neglected his chores and had 'skived off' to go and gather wild plums. On his return, (no doubt to avoid a thrashing) young Robinson told a 'cock and bull story' which was to result in seventeen frightened women being brought to trial in Lancaster on a charge of witchcraft; one of these being Jennet Device, the precocious child witness of the 1612 trials.

Robinson told of how he met two greyhounds with golden collars chasing a hare, one of which turned into Mistress Dickonson, his neighbour, the other dog turning into a little boy. Putting a bridle on the child, Dickonson then had turned the little boy into a white horse and had placed young Robinson on its back, taking them to a witches feast at Hoarstones, from which he had fled in terror, pursued by 'Loynd Wife', 'Dickonson Wife' and 'Janet Davies' (Jennet Device). At Boggard Hole they almost caught up with him, but Robinson had escaped, mainly due to the timely arrival of some horsemen.

This was the story told to the local magistrates, but further bizarre fantasies followed as young Robinson warmed to his task, being no doubt carefully coached by his father, who seems to have had designs on becoming a 'witchfinder', a potentially profitable business in those superstitious times!) In May 1633, Lord Conway was informed by Sir William Pelham of a 'huge pack of witches lately discovered' and the affair began to take on a wider interest.

As a result of Robinson's testimony 17 witches were found guilty at the Lancaster Assizes. The sentence however, was delayed while the presiding judge made a report to the King. Not long afterwards, four of the 'witches' were sent to London, where they were examined by the roayal physicians, who sought to find 'devils marks' (without success as it turned out). Meanwhile in Lancaster, one of the accused, Margaret Johnson, had caved in and had 'confessed all'. Again we get the usual stories of witches sabbaths and familiar spirits. This did nothing to improve the lot of her fellow prisoners. The poor women languished in Lancaster's dungeons for years afterwards, but were mercifully spared the gallows. Young Robinson eventually revealed that his 'evidence' was pure fabrication, and that he had been put up to it by his father, who was duly arrested and clapped into gaol. Thus for once did the ponderous mechanism of justice actually triumph!

So what are we to make of these horrendous persecutions? To modern eyes it seems incomprehensible that educated men could take such childish fabrications so seriously. Yet in casting such a judgement we make the would-be-historian's most frequent mistake:- that of seeing things with the benefit of hindsight. To understand the Pendle witch trials and why they took place it is necessary to delve deeply into the psyche of early seventeenth century England and to try to understand how people saw things at the time.

The Pendle witch persecutions were caused in the first instance by petty jealousies, squabbles and feuds between poor local families which got out of hand. These, combined with the ignorance, self delusion and superstitions of the parties concerned, created a frenzy of accusation and counter accusation, all of which played neatly into the hands of the State, which, for rather more complex reasons of its own was seeking any kind of political 'scapegoat' it could lay its hands on.

The early 17th century was a period of suspicion, intrigue and great brutality. Executions were public spectacles, watched by people for whom the sight of agonising death was little more than a market day diversion.The records of York Castle are filled with such 'spectacles'. The record of 30th April 1649 for example, Tells us that "Isabella Billington aged 32 was hanged and burned for crucifying her mother at Pocklington on 5th January 1649 and subsequently offering a calf and a cock as a burnt sacrifice. Her husband was hanged." How could people be unmoved by horrors such as this? We find it hard to understand, but yet the reasons are not too difficult to find. We simply need to put these things into their correct context.

Modern, western, man is horrified by human pain, because, for the first time in our history, it is unnecessary. The twin 'deities' of modern medicine and scientific technology have removed most of our sufferings, and the end product of those sufferings- death, is discreetly hidden away as we are carefully screened and cushioned from its harsher realities. Society proclaims 'paradise on earth' as its ultimate goal, thus effectively putting 'God and religion' out of a job. The mediaeval mystics who scourged themselves to achieve spiritual purity in order to be 'nearer to God' would today be regarded as suitable cases for psychiatric treatment; yet in the early 17th century suffering was not only universal, but was often seen as necessary and even desirable. Suffering was central to life itself in a society whose purpose was not the pursuit of worldly wealth and happiness but the attainment of spiritual salvation, because only through suffering (as Our Lord suffered) could man hope to attain heaven. To the 17th century mind heaven and hell were not mere hypothesis but FACT.

This idea of universal suffering was central to all aspects of life in mediaeval, Tudor and early Stuart England. Pain (and death) was everyone's constant companion. The agonies endured by condemned criminals could be indentified with the normal agonies of daily life, which afflicted everyone, rich and poor alike. Toothache for example, could only be relieved by the agonies of the blacksmiths tongs, there was no painkilling or surgical treatment to deal with even the mundane tortures of gallstones, gout, arthritis and a host of other (often fatal) maladies. All too often the only relief from agony was death. The appalling punishments reserved for traitors, heretics and witches therefore, hanging drawing and quartering, boiling alive, the stake, the rack were not so much a product of sadism as a desire to both punish the criminal and at the same time cleanse his or her soul of the sins that had been committed. The real horror of a traitor's death was not so much the slow agony, (which people knew how to endure) but the utter degradation and loss of honour and human dignity which such an end entailed.

So much for the brutality. Now let us look at the suspicion and the intrigue. Of all the contemporary information relating to the socio-political climate of early 17th century England, there is one work which stands head and shoulders above the rest. Not a history or a sermon but a play, ostensibly set in dark age Scotland, but with its ideas firmly rooted in the early 1600's. Shakespeare's 'Macbeth' is as topical to the early 17th century as Arthur Miller's play, 'The Crucible' was to the 'witch hunts' of 1950's McCarthyism.

'The Tragedie of Macbeth' was first published in 1623, but certainly was written some time earlier, there being a record of a performance of the play at the Globe Theatre as early as 1610 (two years before the Pendle trials). Shakespeare, like all artists of that age, depended heavily on royal and noble patronage for his livelihood, and in 1603 with 'Good Queen Bess' dead and the crown passing to James VI of Scotland, the creation of a play extolling the virtues of this new monarch must certainly have been uppermost in Shakespeare's mind. So he wrote 'Macbeth', a play rich in royal flatteries, with references cunningly calculated to be of interest to James I. The supposed descent of the Stuart line from the murdered Banquo is an obvious compliment, but more interesting is Shakespeares theme of witchcraft, for as the author of the 'Daemonologie' King James had a special interest in this subject, and indeed had been known to conduct witch 'examinations' in person. Macbeth is a black play, a play haunted by magic, superstition, fog and gloom. Actors even have superstitions about performing it, and it is well known that no-one ever speaks the last line of the play until the first night. 'Macbeth' contains all the classic ingredients of a Jacobean conspiracy- intrigues, suspicions, murder, 'treason and plot'. Only the 'gunpowder' is missing, but we don't have to search far for that either, as the plot of 1605 falls neatly into the period when 'Macbeth' was written, and perhaps Guy Fawkes' attempt to blow up the monarch influenced Shakespeares work. There is no evidence to suggest that Shakespeare believed in his 'witches', in fact it seems more likely that he did not, his witches being merely a device on which to pivot his story. But in any case, the inclusion of witches in Macbeth serves an even more subtle purpose than the mere flattery of a superstitious reigning monarch - they were in fact Shakespeares chief vehicle for setting the scene of 'Macbeth' - not in ancient Scotland but in early Jacobean England!

The key word is 'equivocation':- a word which occurs frequently in 'Macbeth' and indeed sometimes seems to be almost the main theme of the play. 'Fair is foul and foul is fair' say the witches in scene I, and significantly, the first lines of an innocent Macbeth - "So foul and fair a day I have not seen" echoes this ongoing theme of 'double entendre'. At the end, 'despairing of his charm', Macbeth curses the witches:- "....and be those juggling fiends no more believed that do palter with us in a double sense, that keep the word of promise to our ear and break it to our hope." The porter, (the sole comic character in the play) admits 'an equivocator, that could swear in both scales against either scale, who committed treason enough for God's sake, yet could not equivocate to heaven'. Why, we might ask, was there such an obsession with deceit, conspiracy and double meanings?

The reason is that the real 'political bogeys' of Elizabethan and Jacobean England were not so much witches as the agents of the Counter Reformation; particularly Jesuit priests. (Did they not give the word 'jesuitical' to the english language?) The Stuart court was alive with fears of catholic plots, which were sometimes (as in the case of Guy Fawkes et al.) not entirely without foundation. To english protestants the Jesuits represented the spearhead of attempts by the catholic superpowers of Europe to overthrow the protestant state, restore the 'old faith' in England and purge the land of heretics. These english 'heretics' had not forgotten the reign of Mary Tudor and the fires of Smithfield, and in many an english church one could find the story of those terrible persecutions enshrined in 'Foxes Book of Martyrs'. The reign of Elizabeth had both restored the Church of England and created a 'settlement' which included draconian laws directed against english catholics. Whilst the defeat of the Spanish Armada had seen off the catholic military threat, it had not (despite an admirable display of english catholic loyalty during the crisis) removed the ever present fear of subversion from within, and with the accession of James I and the subsequent catholic plots, this fear had intesified, resulting in an even more rigourous suppression of papists.

The rise of puritanism in the early 17th century further enhanced this climate of suspicion and fear of papism, and in the common (Sun reading!) mind 'witchery' and 'popery' were but different cells in the same cancer. Yet if the South had not forgotten the 'fires of Smithfield' it is also worth remembering that the North had not forgotten the consequences of the 'Pilgrimage of Grace' and the 'Rising of the North' in 1569, and it is not surprising to discover that the main hotbeds of 'popish recusancy' (ie clinging to the 'old catholic faith') were in the North, particularly in Lancashire, where most of the local gentry were secret roman catholics.

This brings us neatly back to the Pendle Witches, and to 'political scapegoats', for, witches or not, the Lancaster women were the victims of this same socio-political paranoia. Not only did the law and the scriptures demand the rooting out of witches, it was also 'fashionable' to do so, and along with the rooting out of recusants and priests, it came politically under the heading of what we today might call 'defence of the realm' or 'war against terror'. This accounts for the zealousness of Magistrate Nowell, and others.

This lack of distinction between agents of the Pope and agents of the Devil cannot be doubted. Little Jennet Device, for example, confessed that her mother had taught her a spell to 'get drink', which, within an hour of casting had resulted in drink coming into the house in a 'very strange manner'. The words of the spell went as follows:-

CRUCIFIXUS HOC SIGNUM VITAM ETERNUM. AMEN!

Without having recourse to a latin dictionary it does not take too much imagination to work out what this means:- 'The sign of the cross gives eternal life!' Hardly the black magic of a pagan witch! It is significant, however, that the ignorant, illiterate Demdikes saw such words as being 'magic', and that this, along with other such 'spells' simply harks back to Pre-Reformation days and the latin liturgies of the mediaeval Church. With 'spells' such as these it is hardly surprising that in protestant eyes the Pope and the Devil were one!

Lastly, and perhaps most significantly of all, we must consider the fate of poor Alice Nutter. That she was a victim of a malicious conspiracy seems certain, even her own family refusing to help her escape the gallows. Whilst denying witchcraft, she could not disprove her presence at the Malkin Tower meeting. But why? It seems unlikely that a woman of her standing would have attended a meeting of beggars in a filthy hovel. Perhaps the key to the mystery lies in the date of the meeting:- Good Friday, 1612. Alice was a Catholic, and it seems more likely that she was attending a secret Good Friday Mass. To have revealed this to her accusers would have meant incriminating a whole host of people, with disastrous consequences. The penalties for attending masses and for harbouring priests were severe, and the fate reserved for captured priests was particularly ghastly. Many a Lancashire gentleman's son was trained and ordained at a continental seminary, in order to be smuggled back into the country to officiate at secret masses. Some of them were caught, and for these poor wretches was reserved the full vivisection and degradation of a traitor's death. Alice Nutter knew full well what might be the consequences of her indiscretion, so she kept silent and took her secrets with her to the gallows.

A final question:- were the Pendle witches truly witches? Certainly in the modern sense they were not; today the likes of Demdike and Chattox would be seen as ignorant and foolish old women, and indeed there were people living at the time who must have thought much the same. The difference though, is that these people would never have dared to be openly sceptical:- in the world of 17th century religious fanaticism to deny the existence of the Devil was to deny the existence of God, so those who debunked witchcraft ran the risk of being accused of Atheism - an even more heinous crime! 21st century morality dwells in a very grey environment, the product of an informed and heightened awareness of subtleties which make the distinctions between 'good' and 'evil', 'right' and 'wrong' often not so easy to define. In our time, while the struggle between the 'good' and the 'bad' guys continues on the TV, we can also accept that in the real world virtue is often unrewarded and vice frequently unpunished. No 17th century mind could possibly accept the modern Bismarckian dictum that 'God is on the side of the larger battalions'. The brilliant and cynical renaissance 'realpolitik' of Maciavelli's 'Prince', which today makes such unsensational reading, was, in the eyes of the Tudors and early Stuarts an evil book, and its author 'the devil incarnate'; for the idea that evil and corruption might reside in the law, the State, or even the Church was quite unthinkable. The Catholic Inquisition might well have gone down in history as an instrument of great evil, yet to the contemporary Catholic Church it was an instrument for good, its tortures intended to bring poor sinners back to God!

But what of the 'witch' - the victim of the sectarian prejudices of all parties? Well, she was either innocent (as in the case of Alice Nutter) or else, like Chattox and Demdike, genuinely believed herself to have magical power over others.(Although there is no evidence of any witches using these 'powers' to save themselves, as one might expect). No,:- in the Jacobean world not only did 'good' always triumph over 'evil', it had to be seen to do so. Any suggestion that these 'witches' might be harmless deluded old crones was beside the point:- they had to die as an example to others of both the spiritual infallibility and absolute power of the State. Today we would call them 'communists' or 'jews' or latterly 'islamists':- largely innocent people innocent people 'fitted up' by the State to serve political ends. In the 17th century the 'war on terror' was directed at witches and catholic conspirators - real or imagined.

Poverty, ignorance and desperation created the Pendle Witches. Poor, ragged and oppressed they vented their frustrations and anger against an unfair, grasping world in the only way they knew how, by the formulation of 'ill-wishing charms', by crushing pathetic clay dolls and casting imagined spells. We might scoff, but only recently I read of the proprietor of a burgled 'new age requisites' shop who announced she had 'hexed' the miscreations with a powerful charm! (Needless to say, arrest and trial did not follow!)

Perhaps the 'witches' laboured under pathetic delusions about themselves, but it must be remembered that old medicines, superstitions and popish/pagan practices were the country people's legacy of ancient pre-christian times. The absorption of pagan beliefs by the early church mentioned elsewhere in this work created a 'folk culture' which was to fuel many witches bonfires in the years following the Reformation. It seems unlikely that the 'witches' danced naked at unholy sabbats before the Devil or indulged in the various obscene acts they confessed to. Rather such intellectual 'treats' were more based in the erotic fantasies of the witches accusers than in the stark, poverty stricken reality of rural Lancashire.

Having said all this though, there is no smoke entirely without fire. The Pendle Witches would not have been above concocting potions and talismans, or believing in their efficacy. In the 'Witches Museum' at Boscastle in Cornwall there is a vast collection of such 'charms', devised for both magical 'attack' and 'defence'. Neither are they all ancient, many of them being quite recent in origin:- mutilated photographs, a knitted 'voodoo doll' in an ATS uniform with pins inserted into a cloth 'heart'., all these things testify to the last resort of the helpless:- the universal human urge to practise magic. This 'urge' can manifest itself in many forms, and we often practise magic without fully realising that we are doing so, be it burning Guy Fawkes in effigy on November 5th or throwing darts at a picture of the Prime Minister! Perhaps the driving of someone to distraction with endless anonymous phone calls could be the most modern form of 'ritual magic' in use!

While we might be inclined to make light of such things and laugh at anyone who could believe in the efficacy of witchcraft, it is worth bearing in mind that, (as any psychiatrist will tell you) we are dealing not with the real world of conscious reality but with the realm of the subconscious, a chaotic, unreal intangible environment where different rules apply. The more intense the feeling the more 'potent' the magic and the more likelihood of it being taken seriously, (which is what, after all, creates the desired effect!) SYMPATHY is the byword of the magician, the idea that 'like begets like'.

Don't believe it? Yes you do! You might accept that if an Australian aborigine points 'the bone' at another Aborigine the victim will die, but he could never inflict his curse on you, you are a modern, civilised person (aren't you?)

Well, yes, you are:- but tucked away deep in your unconscious mind is an ancient 'race memory', a memory of that 'primaeval landscape' from which we all came, and which today we only encounter in the odd dream, or our children's fairy stories. That part of your mind, whether you like it or not, DOES believe in fairies, UFOs , things that go 'bump-in-the-night and the power of magic, all of which we tend to file away under neat headings like 'auto suggestion' or 'ESP'. What this part of the human brain is capable of we have yet to discover, and it may be that all our 'familiars', 'ghosts' and 'close encounters' are but manifestations of our collective psychic expectations. One thing is certain:- magic can work - its only the 'why' that's open to debate. A favourite propaganda ploy of the Nazis was to place a few frames of film bearing an anti semitic slogan in the middle of a real of conventional movie footage. These tiny clusters of film would be inserted at regular intervals. Watching the movie you wouldn't notice the hidden message, so quickly would it flicker by, but your unconscious mind not only noticed, but read it also, (this is why you are now mumbling to yourself that 'Jim Jarratt is brilliant!). This so-called 'subliminal advertising' is now banned in most countries. It is a good example of how your thoughts and opinions can be externally manipulated without your knowledge , and this, more than anything else is the essence of what witches (and stage magicians!) call 'magic'.

If there is a moral to all this it is that perhaps we should keep an open mind upon subjects like the Pendle witch trials. Perhaps the Demdikes and Chattoxes were just harmless beggars, but then again maybe they were not! It matters not that the spells which they were supposed to have incanted were nonsense, or their clay images pathetic; such trivialities are not the substance of any 'magic' but merely its tools. The 'magic' ingredient is belief, conscious or otherwise. If I try to heal your sore throat by singing the Latvian National Anthem and wrapping you up in a rottweiler's bath towel, then Lo! Your throat will be healed:- if you believe it!

So it must have seemed to Roger Nowell on that fateful day in 1612, when he, too, was asked to keep an open mind...............

BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE

Copyright Jim Jarratt. 2006

Whalley to Blacko

"Our food is scanty, our garments rough; our drink is from the stream and our sleep often upon our book. Under our tired limbs there is but a hard mat; when sleep is sweetest we must rise at a bell's bidding. Everywhere peace, everywhere serenity and a marvellous freedom from the tumult of the world."

AILRED OF RIEVAULX - The Mirror of Charity.

Whalley dreams! A backwater-ish kind of town, its Town Gate is its hub, bustling, yet spared the really heavy traffic which thunders at a distance to the north and east. Obscure, yet possessed of a noticeable vitality, Whalley has a modern facade which neither betrays nor disturbs the slumbers of its rich antiquity. Step off its main street, following the pathway which runs across the green sward of St. Mary's Churchyard and you can travel back in time, to the beginnings of a story and the start of a journey.

And what better place to start a journey?? Whalley is situated on the northern bank of the Lancashire Calder, slightly to the south east of where it flows into the Ribble. Southwards, Whalley is dominated by its tree capped Nab, but in the context of this work our attention is drawn towards the east, where rises Wiswell Moor, the most westerly bastion of the long ridge which culminates in the 'Big End' of Pendle Hill, our first 'beacon' and ultimate destination.

Whalley is best known for its Abbey, and one might be forgiven for thinking that Whalley's story starts there, but this is not the case. To find Whalley's beginnings we must in fact travel much further back in time, to a wild landscape from which the legions of Rome had not long ago departed. A mere few miles to the west the gaunt ruins of their fortress at Ribchester (Bremetenacum) still formed the hub of a network of decaying military roads which would still have been in use on that fateful day, when an itinerant priest first sought to bring the word of God to what then would have been little more than primitive huts in a remote forest clearing.

The name of this determined priest was Paulinus, and his mission was to bring Christianity to the fierce and pagan peoples of Northumbria. He had started with the King. About the year 625, Edwin the Great married Ethelburga, sister to the king of Kent, the second most powerful king in Britain. Ethelburga was a zealous Christian, and would not consent to marry Edwin unless she was allowed to exercise her religion without disturbance. Edwin, a pagan, reluctantly agreed. Among the new queen's retinue was Paulinus, who had been consecrated as Bishop to the (then) non-existent See of York by Justus, Archbishop of Canterbury. Edwin at first refused to embrace Christianity, but on Easter Eve 646 his queen bore him a daughter, and so moved was he at Paulinus' great and sincere joy at the news of the queen's happy delivery, that he consented to the baptism of the child, and in the following year he himself embraced the Christian religion, being baptised in a hastily constructed wooden church on the site of what is now York Minster. Thus began the conversion of Northern England to Christianity.

And so Paulinus and his later followers came to Whalley, and where they preached were erected Whalley's oldest monuments, the three dark age crosses that stand in what is now the churchyard. Experts argue as to the exact date of the crosses, some authorities dating them to the 10th century A.D. Some suggest that they are, in fact, celtic crosses, erected by a Scottish mission from Iona. Tradition, however, asserts that Paulinus preached here, and tradition (which often has a habit of proving experts wrong!) is good enough for me, and more appealing!

Christianity replaced paganism, but it did not (or more likely could not) eradicate many of the pagan practices it encountered. Old ways die hard, and centuries afterwards the Church would still be permeated with traditions, art, saints and festivals, many of which owed their origins to pre- christian practices and beliefs. Even after the Reformation, backward, rural Lancashire still stuck obstinately to Roman Catholicism and the 'Old Faith'; perhaps it was the fragmented survival of an even older faith which brought that sad group of women known as the 'Pendle Witches' to their doom on the gallows of Lancaster Moor in 1612.

Local tradition asserts that anyone who can decipher the 'hieroglyphics' on the largest of Whalley's three crosses will learn the secret of invisibility. The 'hieroglyphics' however,, are not so much a form of writing as the forceful, convoluted and vigorous rings, lozenges and spirals so typical of dark age celtic and viking art. They echo a psychic world peopled with dragons, serpents, atavistic impulses and elemental forces. The cross within the wheel, the symbol of Christ's love, is the unifying factor which holds them in place - the holy cork that keeps the pagan genies 'in the bottle.' The rings, lozenges and spirals have a deep psychic significance of far greater antiquity than even these ancient crosses, as we shall see. (This very boldly carved cross also represents the 'Tree of Calvary' another symbol which has a deep rooted pre-christian significance, and which we will be exploring elsewhere on our journey).

In the wake of Whalley's crosses came its church. According to tradition it was originally wooden, and known as the 'White Church under the Hill'. Certainly by 1086 the authors of Domesday could write "The Church of St. Mary had in Wallei two carucates of land free of all custom", (a carucate being the amount of land that a team of oxen could plough in a year - usually about 120 acres.) Certainly by the time of the Conquest Whalley had been long established as a centre of christian worship.

About 1080 what was probably the first stone church on the site was constructed, some of the stone being looted from a roman building, or perhaps from nearby Ribchester. (Part of the arch over the north door of the church, for example, is inscribed 'Flavius', and a stone at the western end of the north aisle is carved with a relief of the god Mars, and was probably part of a roman altar.) This first stone church did not last long, and was probably destroyed by fire, the building of the present church being begun around 1200.

To go into the subsequent history of this lovely church is beyond the scope of this work. Suffice it to say it is a treasure house worthy of leisurely exploration. I was particularly struck by its magnificent choir stalls, carved about 1430 and brought from the nearby Abbey after its dissolution in the reign of Henry VIII. The misericords (the undersides of the seats) are beautifully carved, and evoke all the vibrance and superstition of the Middle Ages. They include a dragon, a man shoe-ing a goose, a swine beneath an oak tree, a soldier being beaten by his wife with a frying pan, a weeping satyr, a fox stealing a goose, St. george and the Dragon and perhaps most significantly of all, a 'green man' with boughs issuing from his mouth. (He also appears in the carved arches above the stalls). If Whalley ever possessed a pagan deity, he would surely have been it. Green George, Jack-in-the-Green, the May King, patron of fertility and forest, remnant of ancient rituals which at one time almost certainly involved human sacrifice. In the Middle Ages he would be transformed into a symbol of the struggle of Anglo Saxon England against the yoke of Norman tyranny - the Man in Lincoln Green, Robin Hood. Then, much, much laster 'Green George' would appear yet again, this time inj the guise of 'General Ludd' mythical leader of Luddite machine breakers! Thus as the Celts had their King Arthur to personify the aspirations of their race, so the English had their Robin Hood - their 'Green Man'.

From the choir stalls of Whalley Church we move to their point of origin. Whalley Abbey is approached through its magnificenr mediaeval gatehouse, where a flag with three fishes, (the Abbey's emblem) flutters gaily in the breeze, alongside the Union Flag. Whalley Abbey has a curious history. Its roots lay with the Cistercian Abbey of Stanlaw, near modern Ellesmere Port, which lay on a point jutting out into the River Mersey and had been founded in 1186. This abbey was frequently flooded by the river, and this, combined with their church tower having been struck by lightning and the abbey near destroyed by a disastrous fire, spurred the monks into searching for premises elsewhere. Thanks to the generosity of Henry De Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, (whose ancestor, John, had originally endowed the Stanlaw foundation) the monks had been granted lands in the Whalley area, so in 1283 they applied for Papal and Royal permission to move here and establish a new abbey.

So it transpired that in 1288 an 'advance guard' of six monks arrived in Whalley. But why Whalley? The choice of site seems inconsistent with a monastic order whose general practice was to establish their abbeys in the wildest and remotest places they could find, far from the habitations of men; for in this singular respect the choice of Whalley was quite unsuitable. Not only did Whalley already possess a long established, existing church, with its attendant village community, it also lay within the sphere of influence of nearby Sawley Abbey, 7 miles to the NE; and it seems likely that both the Abbot and monks of Sawley, and the then Rector of Whalley, Peter De Cestria, both resented the prescence of these upstarts from Merseyside! Perhaps it was due to local difficulties caused by these parties that the foundation stone of Whalley Abbey was not laid until 1308. (By Henry De Lacy.)

Arms of Whalley Abbey

Altogether the great abbey took 127 years to construct and a mere 92 years after its completion came the Dissolution! As Cistercian Abbeys go Whalley was a bit of a latecomer, and this perhaps explains the uncharacteristic lavishness which went into its construction. (The Cistercian Rule had become somewhat lax since the Days of St Bernard and Ailred of Rievaulx). Certainly no expense was spared - french masons and italian woodcarvers were hired, and, as the choir stalls now in the church so amply demonstrate, there was a tremendous ostentatiousness, quite out of place in an order whose rule had always been no carvings or images and a life of harsh austerity! And Whalley Abbey not only looked well..... it lived well. The last Abbot of Whalley, John Paslew (of that family who once dwelt at East Riddlesden Hall near Keighley), spent £500 out of the abbey's £900 income on food - raisins, figs, dates, sugar, currants,cinnamon,almonds, nutmeg, ginger, liquorice and cloves; not to mention wine and large quantities of meat! The Abbot and his guests lived in lordly style - a style fated to quite suddenly disappear with the arrival of the 'tumult of the world' in the form of Henry VIII's Commissioners in 1537.

In 1520 Brother Edmund Howard was reputed to have appeared after his death to Abbot Paslew, warning him of dire events to come. The prophecy came true. In 1536 the Pilgrimage of Grace erupted in the North in protest at Henry's religious reforms and Paslew was unwillingly drawn into the rebellion by William Tempest of Bashall, who forced the Abbot to open his gates with the threat of fire. Paslew's compliance was to cost him dear - the rebellion collapsed, and his implication, along with his refusal to take the oath acknowledging Henry as Head of the Church, resulted in his being hanged, drawn and quartered at Lancaster on 9th March 1537, along with various other brothers from both abbeys in the area. (Tradition would have it that he was hanged in his own doorway, but the evidence does not support this story).

Because St. Mary's Church was available nearby, no attempt was made to spare the abbey church, and the mighty building with its transepts and massive cathedral-like dimensions was levelled to its foundations, which are all that remain today. The rest of the abbey fared better :- both its gatehouses have survived, and part of it was turned into a private house, which became the home of the Assheton family.

The ruins that remain, set in a peaceful garden, are quite impressive. The house is now a Church of England conference centre and retreat, whereas the western part of the cloister, the cellarium and lay brothers dormitory and refectory, are now in the grounds of the Roman Catholic Church of the English Martyrs. Consequently the cloister is cut in two by a modern boundary wall worthy of central Berlin! It is a poignant (and modern) reminder of the differences in belief which originally brought this once magnificent building to its present state of ruin.

Two items caught my interest as I explored the grounds of Whalley Abbey. One of them was the curious pair of rectangular pits to be found in the centre of what was originally the nave. Here stood the choir stalls, now in St. Mary's Church. The pits were originally floored over with oak, and were designed to give greater resonance to the voices of the choir: - a sort of mediaeval public address system! The other item that caught my interest was the cloister, in some respects more the heart of the abbey than the church itself. It was here, in the slype, the passageway that leads to the abbot's lodging, that the Abbot of Kirkstall, on an unofficial visit, was savagely attacked by one of the Whalley monks! Such was the mildness and gentleness of white robed Cistercian brothers! Yet despite these rather odd 'hiccups', life at Whalley must, generally speaking, have been peaceful indeed. In the southeastern corner of the cloister stands the remains of the lavatory, or washing trough. (The meaning of the word has altered - what we call a lavatory, they refered to as a rere-dorter or garde-robe). The trough is surmounted by a stone canopy adorned with a fylfot or swastika, a curiously pagan emblem for a christian monastery. Why? I thought. A study of the Cistercian Rule seems to provide the answer. The swastika is the ancient indo-aryan sun wheel, and the monks of Whalley lived their lives by the sun. At sunset they retired to the dormitory until the hour of midnight, at which time, ('when sleep was sweetest') they were summoned to service in the church. The service over, they then filed into the cloister, where time was spent in prayer and reflection until sunrise, when the monks proceeded to the refectory and had breakfast, (ie 'broke their fast'), first washing themselves at this trough as the first light of dawn fell on the carved sun wheel above their heads!