THE BEACONS WAY

SECTION 2.

Blacko to Cononley

"We found it up yon brist on t'top,

In an outcrop of shiny rock,

Thers grouse an' sheep in t'wind an' t' rain

When we've finished it waint be t'same....

K HANNAM 'Wiseman's Level'.

At Blacko Cross we are starting to leave Pendle behind. Only a short while ago, leaving Firber House, the great Hill seemed to dominate everything, but now, looking down towards Barrowford and Colne in the valley below it seems to be somehow forgotten as the landscape softens and 'civilisation' looms nearer.(If refreshment etc be desired the little community of Blacko - the birthplace of comedian Jimmy Clitheroe - is just down the hill.)

Blacko Cross, a stone of uncertain antiquity, stands just beyond a gate at the side of the road. From here, a route leads along the wallside to Blacko Tower, but the fastened gate, the barbed wire and warning notice make it abundantly clear that your presence is not desired in these domains. So, suitably daunted, you turn right down the road towards Blacko, picking up a stile and 'FP' sign on the left, from which a path leads over fields to mud and barking dogs at Brownley Park.

At Blacko Hillside, the next farm on, a choice must be made. An indistinct path on the left leads up the hillside past hawthorns and a gully to a wall stile, from which a left turn leads directly to Blacko Tower. The alternative is to continue onwards to Malkin Tower Farm (although you can backtrack from near Green Bank and see both if you have the energy). The choice is yours!

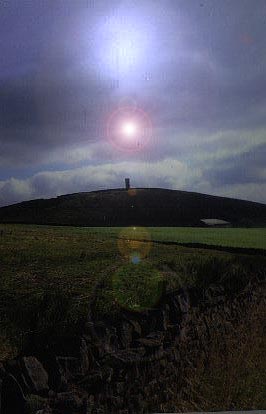

Blacko Tower is a curious place. Blacko means 'Black Hill', the 'o' part being simply a corruption of the better know 'haw' or 'how', a name frequently encountered on hilltop sites, usually in association with barrows and tumuli. No doubt in times long ago this lonely hill also would have possessed its prehistoric burial cairn. Standing at 1,108 feet above sea level, its view is nowhere near as impressive as that from Pendle Beacon, but it is not bad all the same.

Blacko Tower (also known as 'Stansfield Tower'), was built around 1890 by one Jonathan Stansfield, a local grocer who according to legend hoped to see over into Ribblesdale from it, only to find that it was not high enough and he was left with a useless folly. One day in 1964 the sun rose over the hills to disclose a tower that had been mysteriously whitewashed during the night! Who did it? And Why?? The culprits were never found and the mystery remains.

The area round Blacko Tower seems to court mysteries. Many years ago a bronze age axehead was found near here, implying that this hillside had significance to people who lived here long before the age of eccentric Lancashire grocers! I recall once driving home from Morecambe on a summer evening and passing this way, having followed a route through nearby Gisburn. The sun was low in the sky and rooks were circling the tower. It seemed to me a magical, haunted place, faintly reminiscent of Glastonbury Tor... a perfect place for a gathering of witches! Certainly people have some strange ideas about the place:- according to author Guy Ragland Phillips Blacko Tower is a nodal point (ie meeting place) of numerous mysterious 'ley' alignments. Far be it from me to either confirm or refute this assertion, 'leys' always having been a subject of potential controversy among archaeologists and antiquarians.

These mysterious 'straight track' alignments were first 'discovered' bt Alfred Watkins, a Herefordshire brewers representative and keen amateur antiquarian, who, on 30th June 1921, saw in an inspired flash of vision that churches, ancient boundary stones, ponds, beacons, holy wells, mounds, tumuli, wayside crosses, crossroads and a host of other landmarks could often be interlinked, being sited along straight, invisible alignments criss- crossing the landscapes of Britain. These alignments he called 'leys', and in his book, 'The Old Straight Track', Watkins went on to reveal a whole network of ancient 'straight tracks', forming, what for him was a simple and ingenious system of prehistoric road communication. 'The Old Straight Track' is well reasoned, plausible and makes a great deal of sense, and to read it without other information is to be 'converted'. However, Watkins' theories were (and still are!) frowned upon by the archaeological establishment; and with good reason, for while archaeologists will concede that straight alignments between prehistoric sites can and frequently do exist, they will not subscribe to Watkins' 'ley networks' on the grounds that his 'ley identification' criteria are unscientific. Their main argument is that the sites which characterise leys seldom, if ever, belong to the same historical periods. Of course the counter arguments to this are the evidences of folklore and the 'christianisation' and continual re-using of significant and sacred sites. The early Church, it is well known, managed to 'convert' a staunchly heathen Britain to Christianity in less than a century, but yet the real truth is that the conversion was often more apparent than real and had been achieved by compromise rather than by the awesome power of the Gospels. Pagan practices were, in fact, to prove a headache to Christian clerics for many centuries to come.

Yet ironically it is not the arguments of the archaeologists which confound Watkins' 'Straight Track' theories, but the subsequent discoveries of the 'Ley Hunters' themselves! Years of surveying and exploration using Watkins' own identification formula have uncovered a vast network of leys so numerous, and running so closely together, that whatever their purpose, they could never have been ancient trackways! Suddenly we have left the sober world of archaeology behind and entered the rather 'headier' realms of the paranormal.

So, assuming that there is more to leys than people drawing random straight lines on maps, what are we left with? Geomancy, dragon lore, dowsing, witchcraft, UFO sightings and all manner of 'psychic phenomena' have been associated with leys at one time or another. Of these, perhaps the most compelling is the assertion that leys are connected with some kind of magnetic force lines in the earth's crust. Certainly the Earth is a magnet, and so physical laws dictate that such forces should exist. Dowsers definitely seem to think so, and their repeated experiments at ancient sites have revealed a strange connection between the 'ley networks' and these mysterious 'earth currents'. Whether or not such 'forces' exist, must, of course, remain a subject of controversy. Dowsers often ascribe their ability to find water to their sensitivity to these mysterious 'earth forces'; but why?? Fantastic? Fanciful? I do not preseume to know. I do know, however, that dowsing WORKS.

Does Blacko Tower lie at the heart of a web of mysterious pseudo-magical forces? I don't know. I certainly didn't feel them when I was there, but then psychic powers were never my strong point! I wonder if Stansfield was aware of any such 'vibrations' when he built his tower? On the datestone is the biblical reference PS 127 VI. The Psalm to which this refers is well known:-

"Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it,

Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain...."

So was Blacko Tower built to satisfy the eccentric whims of a Lancashire grocer, or was there a more subtle purpose behind its construction? Was it perhaps an attempt to 'christianize' a pagan site - a sort of victorian Paulinus cross? If the legend be true poor Stansfield must have laboured 'in vain'. For he never managed to see over into Ribblesdale and the Devil (presumably) took his tower!

Our next port-of-call is Malkin Tower Farm. Here, (you might be forgiven for thinking) is where the Pendle Witches held that fateful 'gathering of the clans' on Good Friday 1612. Unfortunately, what we would like to believe is often untrue, as the actual location for THE Malkin Tower is, in fact, one of the great mysteries of the Pendle 'Witch Country'. Various excavations have in fact been undertaken to try and find it, without success. Knowing the social status of the 'Demdikes' it was unlikely to have been a structure of much significance, being probably little more than a draughty stone hut. Various places have been suggested for its true location. Walter Bennett maintains that it stood in 'Malkin Field' at Sadler's Farm, Newchurch-in-Pendle. Other people are equally convinced that it lay somewhere between Blacko and Newchurch, or further afield, to the north. In 'Macbeth' one of the witches refers to her familiar as 'Greymalkin' - a cat, but deeper research would suggest that the word 'Malkin' means 'a scarecrow' or simply 'untidy'. It is sometimes encountered as a surname.

Certainly if the witches ever did meet here, in the vicinity of Malkin Tower Farm, then the visualization of this event must be left not to my dull scribblings, but to the imaginations of you, my readers. Just beyond Malkin Tower Farm, where the path turns left up the hill, there is a section of masonry wall which does not conform to the rules of drystone wall construction. Here, (in my imagination at least) lie the remains of 'Malkin Tower'.

Now at last the influence of Pendle Hill is truly receding and new pastures loom ahead. Beyond Peel's House, and the Old Gisburn Road, the route becomes a fine upland promenade along a walled track (Lister Well Road) which leads over some grand shooting moors before finally descending towards Barnoldswick. The views which predominate here are not of Pendle, but of the Yorkshire Dales and the 'Three Peaks' country, a distinctively 'Craven' landscape. Closer at hand is the country around the 'Aire Gap', and soon, to the right, our next objective, Pinhaw Beacon, comes into view. (The adjacent TV booster mast does tend to 'steal the scene' however, Pinhaw itself not being one of the most commanding of eminences.

Finally descending to the valley the Beacons Way just misses the outskirts of Barnoldswick (pronounced - 'Barlick') and briefly joins the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at Park Bridge.

Barnoldswick once had a monastic foundation, which was established in 1147 by an abbot and twelve monks from Fountains Abbey on land given by Henry De Lacy. (Who also helped to establish Whalley Abbey). They did not thrive, and a hostile climate, along with an equally hostile local population eventually forced the abbot (Alexander) to seek a home elsewhere for his brethren, the result being the establishment of Kirkstall Abbey near Leeds, in 1152.

Leave the canal, cross a few potentially confusing pastures and we finally arrive at the little industrial town of Earby, a pleasant and probably by now welcoming community nestling in the valley below Bleara and Thornton Moors. Certainly you will find all mod.cons. here, shops, pubs, etc. all to be found in abundance in this obscure, but cheerful little town, fed by its babbling moorland becks. Earby, (and its larger neighbour Barnoldswick) is to all appearances a typical 'Pendleside' town, sharing an affinity with nearby Nelson, Colne and Barrowford. We are still in Lancashire, and Yorkshire beckons over the hill.

Yet we should not be deceived by appearances, as any remark you might make about Earby being a 'Lancashire town' is likely to be met with fierce contradiction! The fact is that Earby was (and in the minds of its inhabitants still is), in the West Riding of Yorkshire, having been thrown into the hands of the traditional 'enemy' - Lancashire - by the controversial local government re-organisation of 1974, which was an ill-conceived venture giving no consideration whatever to people's sense of cultural identity. The red rose blooms reluctantly in the well tended gardens of Earby!

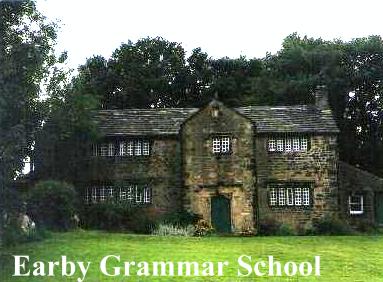

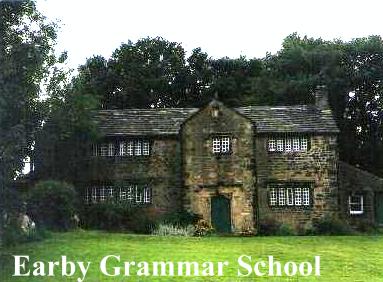

Earby's chiefest jewel is its Tudor Grammar School, which stands amongst trees on a grassy knoll by a junction of roads, hiding coyly from the clattering industrial complex which rears its ugly (but necessary) head just across the way. The Grammar School's origins date back to the reign of Stephen, when Peter De Arthington gave lands in the area for the establishment of a Cluniac nunnery which was fated to be dissolved by the Commissioners of Henry VIII, who in turn rented it to Thomas Cranmer for the sum of twelve shillings a year. Later, after various transactions and changes of ownership the lands were eventually sold, £400 of the proceeds being allocated towards the building of a grammar school to serve the area. The school was duly built,(at a cost of £40) and £20 per annum was given in perpetuity towards the stipend of the schoolmaster. The school was to serve the educational needs of the villages of Thornton and Earby for over 300 years. For a while it became a clinic, but finally was acquired by the Earby Mines Group, who put it to its present use as a museum.

The Earby Mines Museum, after much voluntary work, was finally opened in May 1971, its exhibits being brought in from garages, sheds, lofts and attics all over the area! Since then, many items have been sent back to those places as the museum is now in no way big enough to accommodate the wealth of material that relates to its theme:- the history of metalliferous mining. Tubs, tools, machinery and all the paraphernalia of the miner's life are on display, along with materials relating to mining as far afield as Cornwall and the Yukon goldfields! Copper and tin mining are represented, but, as might be expected, the emphasis tends to be on the lead mining industry of the Yorkshire Dales (evidence of which we will shortly be encountering in an even more fascinating form!). The museum, no doubt due to the voluntary nature of its organisation, has very limited opening hours, being only open in the summer months on Thursdays (6pm to 9pm) and Sundays (2 to 6pm). You are therefore unlikely to catch it open - which is rather a shame!

After topping up the 'fuel tank' in Earby all roads should lead unerringly to the Earby Youth Hostel on Birch Hall Lane. Here at Glen Cottage, (as the plaque says) lived Katharine Bruce Glasier from 1922 to her death in 1950. Katharine and her husband were leading lights in the Independent Labour Party, which was founded in Bradford in the early part of the century. She was a well known speaker at political meetings and was a tireless campaigner in her efforts to improve the lot of working people. One of her greatest acheivements was the establishment of pithead baths for coal miners. She also owned the two adjacent cottages, and in her will she left them all to the YHA, on condition that her housekeeper Mary Holt should live in one of them for the remainder of her life. Naturally enough, Mary and her husband Albert became the hostel's wardens and were to run the 'Katharine Bruce Glasier Memorial Hostel' for nearly 25 years. Mary Holt died in 1987 but her husband continued to live in the adjacent cottage.

Crossing the charming little beck behind the hostel's pretty back garden, Gaylands Lane is reached, and it is not long before we are back on the high moorlands once more. Beyond Hare Hill the Pennine Way is encountered, which joins tarmac at Clogger Lane. Soon, beyond its junction with Elslack Moor Road, amid a rash of prohibitive notices, it leads unerringly around to the summit of PINHAW BEACON.

Pinhaw Beacon, the second beacon in our 'trilogy', is a bit of a disappointment. Standing at 388m, the view across to Pendle is excellent but there is nothing particularly striking about Pinhaw Beacon itself. So outstanding and distinctive is this high eminence in fact, that one feels that the surveyors who erected the concrete triangulation pillar might have entertained doubts as to the 'worthiness' of the site! Equally, one feels that the only reason the Pennine Way comes this way is because the local landowners wouldn't let it go anywhere else! Founded on rock geologically known as 'Pendle Grit', it does at least have this affinity with its distant whale-backed neighbour; but that's about as far as it goes, as the dusty heather moors around Pinhaw are quite unlike the peaty morasses that lie behind the summit of Pendle. All things considered, Pinhaw Beacon as a hill summit has very little to commend it. (But perhaps I am being unkind!)

One thing Pinhaw does have, though, is a story. Ancient man walked these hills, and his settlements still lie below, forgotten earthworks which once stood sentinel over the roman road which ran through the Aire Gap from Ribchester to Aldbrough (Isurium). The Romans, (no doubt looking uneasily over their shoulders) built a fort down below at Elslack to protect this important pass through the Pennines. The site is partially obliterated by a dismantled railway line, and I wonder what the ghosts of the roman legionaries must think of the ghostly railway engines that now shunt through their grassy parade ground??! Yet if the Brigantian tribesmen who lived on these hillsides looked down into the valley in life, they also looked up to the tops of the hills when faced with death. For it was here, on the high moorland ridges that their bodies were cremated and their ashes immured in windswept cairns and lonely burial mounds, destined to stand out as landmarks for peoples yet to settle in these upland fastnesses. The ancient Cleveland 'Lyke Wake Dirge' suggests a tradition of belief in transmigration after death, the conviction that the souls of the dead travelled over the hills to some distant, unknown 'otherworld'. In later, christianised times, the bodies of witches and the unbaptised were frequently buried at crossroads, again suggestive of a belief in some mysterious 'spiritual migration' along 'ways accursed'. Crossroads, landmarks, all these things are suggestive of 'leys', and there are many who would suggest that these urn burials were intended to take advantage of the 'earth currents', natural or otherwise. Equally there are many who would dismiss such ideas as 'bunk'. I prefer to keep an open mind.

Pinhaw Beacon was almost certainly one of these early burial cairns. 'Haw' is a variation of 'How' or 'Howe', a name always associated with hilltop cairns and burial mounds. Long, long ago some ancient local dignitary was buried here beneath a pile of stones, and the place has been a landmark ever since.

As to when Pinhaw first came to be used as a beacon site I am not wholly certain. Certainly it was manned to warn of the threatened invasion of Napoleon, and on a wild, wintry day in January 1805, there were to be tragic consequences as a result. At this time Pinhaw had six guards appointed to man the 'invasion beacon'. In pairs they stood sentinel over this lonely spot in weekly shifts, Elslack, Carleton and Lothersdale each sending up their two guards on a rota basis. A hut was built on the summit of the hill for the two guards to shelter in, and at the start of that fateful year, Lothersdale and Carleton having done their 'stints', Elslack dutifully sent up their two replacement men to man the beacon. One of these was a man called Robert Wilson. For some undisclosed reason the guard post ran out of provisions before the week was up, and Wilson decided to go down to Elslack for fresh supplies. The weather looked grim and was threatening snow, but Wilson saw no reason to worry about this and set off briskly down the moor. In Elslack he secured the much needed rations and set off back up the hill to the beacon. He was never seen alive again.

At the end of the week, Lothersdale sent up its two replacements as usual. After struggling through blinding snow and deep drifts they finally reached the guard post only to find Wilson's partner freezing, starving and raving deliriously. After regaling him with hot drinks, food and blankets he told them of how Wilson had left the hut some days before. After taking the revived guard down to Elslack his rescuers discovered that Wilson had left Elslack long ago, and now it suddenly dawned on them that Wilson was missing on the moors. A large scale search was immediately organised, and it was one of the search party, Jerry Aldersley from Calf Edge, who found Wilson's body in a little hollow, frozen to death, the provisions still at his side! His body was found little more than 150 yards from the hut. A memorial was erected on the spot where he was found, with the inscription:-

"Here was found the body of Robert Wilson, one of the beacon guards, who died January 29th 1805 aged 59 years...."

It is reputed that a head was originally carved on the stone, but if so,it can no longer be seen.

From Pinhaw Beacon the Pennine Way (heading south!) leads down into Lothersdale, although our route branches off before it gets there. Soon, moorland gives way to upland pasture, and as you negotiate the various stiles on the path, it might be wise to passthrough them carefully, especially in view of the ghastly story I am now about to relate........

According to local tradition, one of these upland pastures on the Lothersdale flanks of Pinhaw Beacon bears the unusual name of 'Swine Harrie'. The story goes that 'Swine Harrie' was crossing this field in the dead of night with a pig he had stolen from a nearby farmstead. The pig was tethered to a piece of rope, which was tied in a noose at the thief's end. Still leading the pig on the rope the thief, who was a heavy, burly man, suddenly found his way barred by a ladder stile (no doubt with 'P.W.' carved on it!). Not being very well endowed with brains, 'Swine Harrie' thereupon put the rope around his neck in order to free his hands to climb the stile. On reaching the topmost step he slipped, and hurtled over the other side of the wall. The weight of the pig pulled the rope taut, and the knavish 'Swine Harrie' duly met a just end at the hands (or should I say trotters?) of the animal he had stolen! Bearing this in mind, I would advise you to take care, and if you must take a dog on your rambles, make sure that it's a Jack Russell rather than a Great Dane!

Where the Pennine Way turns right down to Lothersdale the Beacons Way continues onwards past the boggy headwaters of the Stansfield Beck, following a weed choked lane up to Tow Top. Across a field and we enter Babyhouse Lane, where an interesting old milestone serves as a gatestoop in the wall to the right. Carved ' To Kighley 5 miles' it seems quite out of place, and one is inclined to wonder if it was moved to its present spot. Babyhouse Lane continues on down to Four Lane Ends, but before reaching it, earthworks may be seen in the field to the left, just above the plantation. This 'circular camp' is certainly ancient, and according to Speight, Danish, although I am inclined to think that it is more likely to be contemporary with the other ancient earthworks we mentioned earlier. Perhaps modern archaeology has since found the answer.

At Four Lane Ends we turn left towards Cononley. According to legend, there was once a gibbet here at this ancient crossroads. 12 felons were reputedly hanged, their bodies being buried by the roadside. It is said that the last man to be gibbetted here was a horse thief named Singleton, some time at the beginning of the 19th century. Be that as it may, this story, apocryphal or not, has echoes of old pagan practices and beliefs. It was not for nothing that a 'Pentitential' from the time of Egbert said that "any woman who would cure her infant by any sorcery, or shall have it drawn through the earth at the crossroads, is to fast for three years, for this is great paganism." Was not Odin the patron of the crossroads and the gallows? The Norsemen who settled in the northern dales also had their 'Nikkr', a fiddle playing demon, who endowed viking youth with the gift of music. This pagan spirit is the origin of the old north country belief that if you play a fiddle at a crossroads on a moonlit night you are likely to conjure up 'Owd Nick'. Ultimately, of course, such stories lend strength to the arguments of the 'leyhunters'.

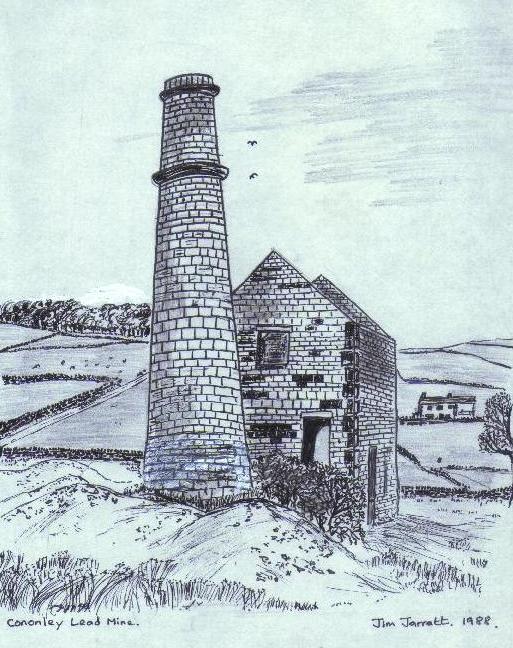

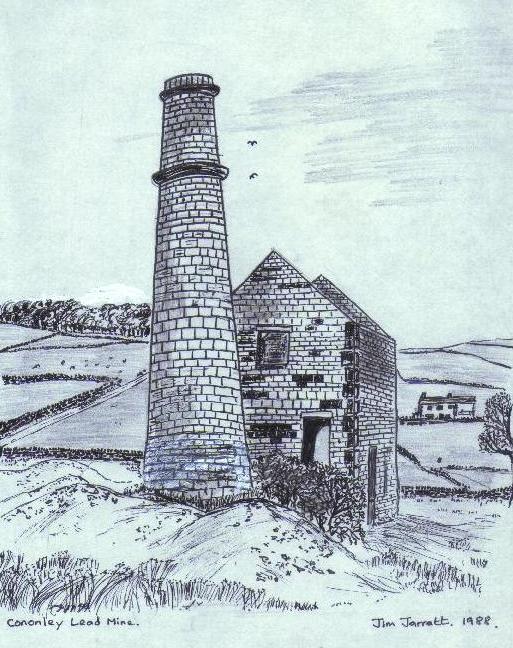

Not far beyond Four Lane Ends, we come to, what is for me at any rate, one of the main attractions of the journey. Down a farm road to the right lies an arid wasteland, quite devoid of vegetation and topped by the quite incongruous apparition of a Cornish engine house! This is the Cononley Lead Mine, which, even as lead mines go, is unusual, being quite out of place in these Airedale uplands, a lone refugee from the spoil heap wastelands of Greenhow, Grassington Moor and Upper Swaledale, where such landscapes tend to be the norm rather than the exception.

The 'raison d'etre' for this industrial oddity, is, of course, a geological one. A single large mineral vein occurs here, being part of a major fault across what is known as the Bradley Anticline. The area was first exploited for its lead ores in the 16th and 17th centuries, and bell pits from this period still survive. The vein was part of the royalty of the Duke of Devonshire and in the 18th century miners were sent here from the Duke's workings on Grassington Moor, in order to try and develop the area's potential. It was not until 1830 however, before the mines began to be fully developed by Stephen Eddy, the Duke's Agent. A level was driven from the side of nearby Nethergill, and this exploratory working, known as Brigg's Level, discovered large quantities of cerrusite, a very soft, easily worked carbonate of lead. From here the mine developed apace and a smelt mill was constructed down the Gill, near Cononley. More levels were driven, Deep Level Crosscut cutting the vein at 205 fathoms. (1230 feet). A main shaft and an incline shaft were sunk and the whole area became a bustling hive of activity. Between 1830 and 1876, when the mine finally closed, it produced some 15000 tons of lead ore. The impressive engine house, more reminiscent of North Cornwall than West Yorkshire served the main shaft, which lies just behind it, capped by a steel grille. The building was lovingly restored by the Earby Mines Group, whose museum we didn't get much chance to see back in Earby.

For me, these old mines have an endless fascination, representing a technology and industrial culture quite apart from that associated with coal mining. It is hardly surprising that the engine house at Cononley looks like a refugee from Redruth - it probably was! Cornish miners were brought to the Dales to work the lead veins, and with them came Cornish techniques and 'know-how'. The tinners also brought their superstitions and beliefs:- 'spriggans','knockers' and all the other elemental subterranean creatures so beloved of the vivid Celtic imagination. Ad to them stories of 'phantom shifts' and ''t'owd men' and we enter the realms of an industry endowed not only with unique methods but also with a unique folklore.

Old lead mines can be eerie places. My first encounter with them was walking from Coast-to-Coast in 1973, which entailed traversing the great lead mined wasteland to the north of the Swale. Later forays took me to Grassington Moor, to Buckden Gill, to the remains of Wiseman's Level near Kettlewell. Some years later, at Trevaunance Cove on the North Cornwall Coastal Path I was amazed to discover 'Swinnergill - on -sea, and suddenly became aware of the similarities between the two mining areas.

It was with Keith Hannam, an experienced veteran caver, that I had my first experience of the 'innards' of some of these old workings:- exploring an adit level near Starbotton, and descending an inclined shaft near Trollers Gill, Skyreholme. I would not advise anyone to undertake such journeys lightly. Specialised equipment, and experienced, knowledgeable companions are not only necessary but vital. It is well known that caves can be dangerous, yet old mines, being man-made are doubly so. Never, ever, enter old mine workings out of mere passing curiosity. It could be the last thing you ever do, for beyond those inviting looking walled entrances lurk death traps galore:- loose earth and boulders shored up by rotting timbers, unexpected (and often flooded) internal shafts and unstable stopes.(Stopes are particularly dangerous - the miners left their gangue - spar and waste materials - piled up on tiered platforms shored up with timbers. The dangers posed by such structures after years of decay and and neglect should be palpably and appallingly obvious.) The moral is simple - KEEP OUT!!

Yet having said this, no-one can deny that old mines fascinate and stimulate curiosity. In your imagination at least, you can venture down old shafts and explore below in perfect safety! The 'underground' beckons, and if you feel you really need to see the 'insides' for real, there are societies you can join, and site museums you can visit. At Wendron, in Cornwall you can don a hard hat, fasten on a cap lamp and explore the interior of a fully renovated tin mine, a living, working museum, where the methods used by metalliferous miners, ancient and modern, are on show for all to see.

The 'working industrial museum' concept is at present, 'state-of-the-art' in the interpretation of our industrial and social past. It is not for me to discuss the merits of Beamish, the Crich Tramway Museum, the National Coal Mining Museum at Caphouse Colliery, near Wakefield and a host of other similar 'working' attractions to be seen all over the country. These places sell themselves, for they give not only a fascinating insight into the past but are also profitable tourist attractions into the bargain.

It seems sad to me that the Pennine lead mining industry, which wrote so much of the history of the Yorkshire Dales and made such a big impact in the shaping of its landscape has no such 'living monument' to its former greatness. The Earby Mines Museum, for all its praiseworthy acheivements, does not effectively rise to this challenge. There is a need for a WORKING lead mining museum, and what better place to site one than here, at Cononley Lead Mine? The site is not far removed from urban centres, and, unlike many of the Dales mines, it is easily reached by car and there is scope for developing parking facilities. Its surface remains are still dramatic, and having both shaft and incline access to the underground workings Cononley could offer great potential for underground tours for members of the public. The mine could be restored, the engine house fully restored, complete with steam engine and shaft headgear. Underground displays could depict the fascinating and often harsh life of the lead miner, and the 'on-the-surface processes of the industry could be housed in a complex of traditional wooden 'shafthead' buildings. Such a process would involve both the outlay of both money and vision in large quantities, factors which seldom go hand-in-hand in our modern, cynical world. Still, I can dream cant I??

Beyond Cononley Lead Mine our route winds around the pastures of Cononley Gib before finally descending to Cononley Village and the end od SECTION 2.

Cononley Gib, crowned with its mine chimney, and scarred by the occasional old working, is a pleasnt spot, giving fine views across the Upper Aire Valley. Particularly to the hills beyond Skipton and to the woodlands and rocks across the way, topped by the distinctive white 'pepperpot' of Kildwick Cross. It is a place of rising valley sounds and bleating sheep.

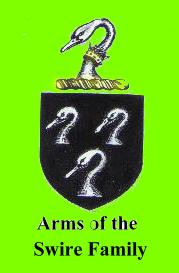

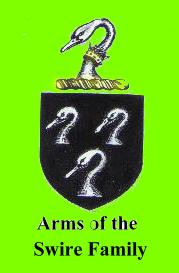

Cononley is an interesting little village. In Domesday it appears as 'Cutnelai' the property of one 'Torchil'. According to Speight the name means 'Canutes Field'. In the Middle Ages lands were held here by both the knights of St. John and the canons of Bolton Priory. The chiefest building of interest in the village is Cononley Hall, a rambling hybrid of architectural styles, being basically a three storeyed georgian mansion grafted onto a 16th century mullioned manor house. Cononley Hall was the traditional seat of the Swire Family, and a stone on the south wall is carved:-

S. E. S.

R. 1683 S

These initials stand for Samuel and Elizabeth Swire, and their son Roger Swire, who died in 1705.

Lead mines apart, Cononley's main industry has always been textiles. Baines' 1822 Directory list amongst the inhabitants of Cononley one Reuben Stansfield, a cotton manufacturer. Also Club Row, a long line of houses conspicuous from the railway were built specifically for the purpose of handloom weaving, being suitably lighted with 'weaving windows' on the upper storeys.

Cononley's beck runs through the heart of the village, eventually pouring into the Aire, not far beyond the railway. Buses to Keighley and Skipton alight at the Post Office, and Cononley's spick-and-span little railway halt gives acces to Morecambe, Lancaster, Bradford and Leeds. For such a little backwater of a village, Cononley seems to be remarkably well served by public transport.

Perhaps it was this easy access to places remote which stimulated the events of Tuesday 23rd January 1886, when the supporters of illegal gaming activities descended upon this sleepy place in great numbers. In those days the lonely moorlands of the Pennines were seen as the ideal location for illegal practices like gambling schools, dog fighting, cock fighting and last, but by no means least, the noble (and illegal) art of bareknuckle pugilism. The advantage of the moors for such gatherings was, (and in some places still is!) their isolation and solitude, it being easy for specially posted lookouts to give good advance warning of the approach of the 'enemy' i.e.- police constables and magistrates.

At 7am on this particular morning in 1886 the Leeds train clanked to a halt at a sleepy and unsuspecting Cononley. From the carriages emerged a host of motley looking individuals whom the local press later described as being "a select assortment of those species of the genus Homo, known in the parlance of certain papers as 'roughs', 'pugs', and 'sporting characters'." This gathering, reputedly some 200 strong and swelled by numerous locals no doubt intent upon 'seeing a fight', made its way up to Cononley Moor, to a place not far from the lead mine; and it was here that Teddy Curley and Tom Parfitt set out to 'do their utmost to maim, lame and mutilate each other in cool blood and friendly spirit' for the purpose of winning a nice, fat prze fighter's purse. Of course when the authorities got wind of what was going on they immediately sent three constables and a superintendent from Skipton, who arrived at Cononley Moor to find the fight over and the crowd dispersing. The constables gave chase to two men who were making off with the ropes and stakes which had been usesd for the ring, but, dropping their tackle, they managed to successfully make their escape. The stakes and rope were taken by police to Skipton, where they were valued at £20. No further such 'fight trains' were recorded. Today, Cononley seems as sleepy as ever, nestling in its hills and dreaming of days gone by..............

BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE

Copyright Jim Jarratt. 2006

"We found it up yon brist on t'top,

In an outcrop of shiny rock,

Thers grouse an' sheep in t'wind an' t' rain

When we've finished it waint be t'same....

K HANNAM 'Wiseman's Level'.

At Blacko Cross we are starting to leave Pendle behind. Only a short while ago, leaving Firber House, the great Hill seemed to dominate everything, but now, looking down towards Barrowford and Colne in the valley below it seems to be somehow forgotten as the landscape softens and 'civilisation' looms nearer.(If refreshment etc be desired the little community of Blacko - the birthplace of comedian Jimmy Clitheroe - is just down the hill.)

Blacko Cross, a stone of uncertain antiquity, stands just beyond a gate at the side of the road. From here, a route leads along the wallside to Blacko Tower, but the fastened gate, the barbed wire and warning notice make it abundantly clear that your presence is not desired in these domains. So, suitably daunted, you turn right down the road towards Blacko, picking up a stile and 'FP' sign on the left, from which a path leads over fields to mud and barking dogs at Brownley Park.

At Blacko Hillside, the next farm on, a choice must be made. An indistinct path on the left leads up the hillside past hawthorns and a gully to a wall stile, from which a left turn leads directly to Blacko Tower. The alternative is to continue onwards to Malkin Tower Farm (although you can backtrack from near Green Bank and see both if you have the energy). The choice is yours!

Blacko Tower is a curious place. Blacko means 'Black Hill', the 'o' part being simply a corruption of the better know 'haw' or 'how', a name frequently encountered on hilltop sites, usually in association with barrows and tumuli. No doubt in times long ago this lonely hill also would have possessed its prehistoric burial cairn. Standing at 1,108 feet above sea level, its view is nowhere near as impressive as that from Pendle Beacon, but it is not bad all the same.

Blacko Tower (also known as 'Stansfield Tower'), was built around 1890 by one Jonathan Stansfield, a local grocer who according to legend hoped to see over into Ribblesdale from it, only to find that it was not high enough and he was left with a useless folly. One day in 1964 the sun rose over the hills to disclose a tower that had been mysteriously whitewashed during the night! Who did it? And Why?? The culprits were never found and the mystery remains.

The area round Blacko Tower seems to court mysteries. Many years ago a bronze age axehead was found near here, implying that this hillside had significance to people who lived here long before the age of eccentric Lancashire grocers! I recall once driving home from Morecambe on a summer evening and passing this way, having followed a route through nearby Gisburn. The sun was low in the sky and rooks were circling the tower. It seemed to me a magical, haunted place, faintly reminiscent of Glastonbury Tor... a perfect place for a gathering of witches! Certainly people have some strange ideas about the place:- according to author Guy Ragland Phillips Blacko Tower is a nodal point (ie meeting place) of numerous mysterious 'ley' alignments. Far be it from me to either confirm or refute this assertion, 'leys' always having been a subject of potential controversy among archaeologists and antiquarians.

These mysterious 'straight track' alignments were first 'discovered' bt Alfred Watkins, a Herefordshire brewers representative and keen amateur antiquarian, who, on 30th June 1921, saw in an inspired flash of vision that churches, ancient boundary stones, ponds, beacons, holy wells, mounds, tumuli, wayside crosses, crossroads and a host of other landmarks could often be interlinked, being sited along straight, invisible alignments criss- crossing the landscapes of Britain. These alignments he called 'leys', and in his book, 'The Old Straight Track', Watkins went on to reveal a whole network of ancient 'straight tracks', forming, what for him was a simple and ingenious system of prehistoric road communication. 'The Old Straight Track' is well reasoned, plausible and makes a great deal of sense, and to read it without other information is to be 'converted'. However, Watkins' theories were (and still are!) frowned upon by the archaeological establishment; and with good reason, for while archaeologists will concede that straight alignments between prehistoric sites can and frequently do exist, they will not subscribe to Watkins' 'ley networks' on the grounds that his 'ley identification' criteria are unscientific. Their main argument is that the sites which characterise leys seldom, if ever, belong to the same historical periods. Of course the counter arguments to this are the evidences of folklore and the 'christianisation' and continual re-using of significant and sacred sites. The early Church, it is well known, managed to 'convert' a staunchly heathen Britain to Christianity in less than a century, but yet the real truth is that the conversion was often more apparent than real and had been achieved by compromise rather than by the awesome power of the Gospels. Pagan practices were, in fact, to prove a headache to Christian clerics for many centuries to come.

Yet ironically it is not the arguments of the archaeologists which confound Watkins' 'Straight Track' theories, but the subsequent discoveries of the 'Ley Hunters' themselves! Years of surveying and exploration using Watkins' own identification formula have uncovered a vast network of leys so numerous, and running so closely together, that whatever their purpose, they could never have been ancient trackways! Suddenly we have left the sober world of archaeology behind and entered the rather 'headier' realms of the paranormal.

So, assuming that there is more to leys than people drawing random straight lines on maps, what are we left with? Geomancy, dragon lore, dowsing, witchcraft, UFO sightings and all manner of 'psychic phenomena' have been associated with leys at one time or another. Of these, perhaps the most compelling is the assertion that leys are connected with some kind of magnetic force lines in the earth's crust. Certainly the Earth is a magnet, and so physical laws dictate that such forces should exist. Dowsers definitely seem to think so, and their repeated experiments at ancient sites have revealed a strange connection between the 'ley networks' and these mysterious 'earth currents'. Whether or not such 'forces' exist, must, of course, remain a subject of controversy. Dowsers often ascribe their ability to find water to their sensitivity to these mysterious 'earth forces'; but why?? Fantastic? Fanciful? I do not preseume to know. I do know, however, that dowsing WORKS.

Does Blacko Tower lie at the heart of a web of mysterious pseudo-magical forces? I don't know. I certainly didn't feel them when I was there, but then psychic powers were never my strong point! I wonder if Stansfield was aware of any such 'vibrations' when he built his tower? On the datestone is the biblical reference PS 127 VI. The Psalm to which this refers is well known:-

"Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it,

Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain...."

So was Blacko Tower built to satisfy the eccentric whims of a Lancashire grocer, or was there a more subtle purpose behind its construction? Was it perhaps an attempt to 'christianize' a pagan site - a sort of victorian Paulinus cross? If the legend be true poor Stansfield must have laboured 'in vain'. For he never managed to see over into Ribblesdale and the Devil (presumably) took his tower!

Our next port-of-call is Malkin Tower Farm. Here, (you might be forgiven for thinking) is where the Pendle Witches held that fateful 'gathering of the clans' on Good Friday 1612. Unfortunately, what we would like to believe is often untrue, as the actual location for THE Malkin Tower is, in fact, one of the great mysteries of the Pendle 'Witch Country'. Various excavations have in fact been undertaken to try and find it, without success. Knowing the social status of the 'Demdikes' it was unlikely to have been a structure of much significance, being probably little more than a draughty stone hut. Various places have been suggested for its true location. Walter Bennett maintains that it stood in 'Malkin Field' at Sadler's Farm, Newchurch-in-Pendle. Other people are equally convinced that it lay somewhere between Blacko and Newchurch, or further afield, to the north. In 'Macbeth' one of the witches refers to her familiar as 'Greymalkin' - a cat, but deeper research would suggest that the word 'Malkin' means 'a scarecrow' or simply 'untidy'. It is sometimes encountered as a surname.

Certainly if the witches ever did meet here, in the vicinity of Malkin Tower Farm, then the visualization of this event must be left not to my dull scribblings, but to the imaginations of you, my readers. Just beyond Malkin Tower Farm, where the path turns left up the hill, there is a section of masonry wall which does not conform to the rules of drystone wall construction. Here, (in my imagination at least) lie the remains of 'Malkin Tower'.

Now at last the influence of Pendle Hill is truly receding and new pastures loom ahead. Beyond Peel's House, and the Old Gisburn Road, the route becomes a fine upland promenade along a walled track (Lister Well Road) which leads over some grand shooting moors before finally descending towards Barnoldswick. The views which predominate here are not of Pendle, but of the Yorkshire Dales and the 'Three Peaks' country, a distinctively 'Craven' landscape. Closer at hand is the country around the 'Aire Gap', and soon, to the right, our next objective, Pinhaw Beacon, comes into view. (The adjacent TV booster mast does tend to 'steal the scene' however, Pinhaw itself not being one of the most commanding of eminences.

Finally descending to the valley the Beacons Way just misses the outskirts of Barnoldswick (pronounced - 'Barlick') and briefly joins the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at Park Bridge.

Barnoldswick once had a monastic foundation, which was established in 1147 by an abbot and twelve monks from Fountains Abbey on land given by Henry De Lacy. (Who also helped to establish Whalley Abbey). They did not thrive, and a hostile climate, along with an equally hostile local population eventually forced the abbot (Alexander) to seek a home elsewhere for his brethren, the result being the establishment of Kirkstall Abbey near Leeds, in 1152.

Leave the canal, cross a few potentially confusing pastures and we finally arrive at the little industrial town of Earby, a pleasant and probably by now welcoming community nestling in the valley below Bleara and Thornton Moors. Certainly you will find all mod.cons. here, shops, pubs, etc. all to be found in abundance in this obscure, but cheerful little town, fed by its babbling moorland becks. Earby, (and its larger neighbour Barnoldswick) is to all appearances a typical 'Pendleside' town, sharing an affinity with nearby Nelson, Colne and Barrowford. We are still in Lancashire, and Yorkshire beckons over the hill.

Yet we should not be deceived by appearances, as any remark you might make about Earby being a 'Lancashire town' is likely to be met with fierce contradiction! The fact is that Earby was (and in the minds of its inhabitants still is), in the West Riding of Yorkshire, having been thrown into the hands of the traditional 'enemy' - Lancashire - by the controversial local government re-organisation of 1974, which was an ill-conceived venture giving no consideration whatever to people's sense of cultural identity. The red rose blooms reluctantly in the well tended gardens of Earby!

Earby's chiefest jewel is its Tudor Grammar School, which stands amongst trees on a grassy knoll by a junction of roads, hiding coyly from the clattering industrial complex which rears its ugly (but necessary) head just across the way. The Grammar School's origins date back to the reign of Stephen, when Peter De Arthington gave lands in the area for the establishment of a Cluniac nunnery which was fated to be dissolved by the Commissioners of Henry VIII, who in turn rented it to Thomas Cranmer for the sum of twelve shillings a year. Later, after various transactions and changes of ownership the lands were eventually sold, £400 of the proceeds being allocated towards the building of a grammar school to serve the area. The school was duly built,(at a cost of £40) and £20 per annum was given in perpetuity towards the stipend of the schoolmaster. The school was to serve the educational needs of the villages of Thornton and Earby for over 300 years. For a while it became a clinic, but finally was acquired by the Earby Mines Group, who put it to its present use as a museum.

The Earby Mines Museum, after much voluntary work, was finally opened in May 1971, its exhibits being brought in from garages, sheds, lofts and attics all over the area! Since then, many items have been sent back to those places as the museum is now in no way big enough to accommodate the wealth of material that relates to its theme:- the history of metalliferous mining. Tubs, tools, machinery and all the paraphernalia of the miner's life are on display, along with materials relating to mining as far afield as Cornwall and the Yukon goldfields! Copper and tin mining are represented, but, as might be expected, the emphasis tends to be on the lead mining industry of the Yorkshire Dales (evidence of which we will shortly be encountering in an even more fascinating form!). The museum, no doubt due to the voluntary nature of its organisation, has very limited opening hours, being only open in the summer months on Thursdays (6pm to 9pm) and Sundays (2 to 6pm). You are therefore unlikely to catch it open - which is rather a shame!

After topping up the 'fuel tank' in Earby all roads should lead unerringly to the Earby Youth Hostel on Birch Hall Lane. Here at Glen Cottage, (as the plaque says) lived Katharine Bruce Glasier from 1922 to her death in 1950. Katharine and her husband were leading lights in the Independent Labour Party, which was founded in Bradford in the early part of the century. She was a well known speaker at political meetings and was a tireless campaigner in her efforts to improve the lot of working people. One of her greatest acheivements was the establishment of pithead baths for coal miners. She also owned the two adjacent cottages, and in her will she left them all to the YHA, on condition that her housekeeper Mary Holt should live in one of them for the remainder of her life. Naturally enough, Mary and her husband Albert became the hostel's wardens and were to run the 'Katharine Bruce Glasier Memorial Hostel' for nearly 25 years. Mary Holt died in 1987 but her husband continued to live in the adjacent cottage.

Crossing the charming little beck behind the hostel's pretty back garden, Gaylands Lane is reached, and it is not long before we are back on the high moorlands once more. Beyond Hare Hill the Pennine Way is encountered, which joins tarmac at Clogger Lane. Soon, beyond its junction with Elslack Moor Road, amid a rash of prohibitive notices, it leads unerringly around to the summit of PINHAW BEACON.

Pinhaw Beacon, the second beacon in our 'trilogy', is a bit of a disappointment. Standing at 388m, the view across to Pendle is excellent but there is nothing particularly striking about Pinhaw Beacon itself. So outstanding and distinctive is this high eminence in fact, that one feels that the surveyors who erected the concrete triangulation pillar might have entertained doubts as to the 'worthiness' of the site! Equally, one feels that the only reason the Pennine Way comes this way is because the local landowners wouldn't let it go anywhere else! Founded on rock geologically known as 'Pendle Grit', it does at least have this affinity with its distant whale-backed neighbour; but that's about as far as it goes, as the dusty heather moors around Pinhaw are quite unlike the peaty morasses that lie behind the summit of Pendle. All things considered, Pinhaw Beacon as a hill summit has very little to commend it. (But perhaps I am being unkind!)

One thing Pinhaw does have, though, is a story. Ancient man walked these hills, and his settlements still lie below, forgotten earthworks which once stood sentinel over the roman road which ran through the Aire Gap from Ribchester to Aldbrough (Isurium). The Romans, (no doubt looking uneasily over their shoulders) built a fort down below at Elslack to protect this important pass through the Pennines. The site is partially obliterated by a dismantled railway line, and I wonder what the ghosts of the roman legionaries must think of the ghostly railway engines that now shunt through their grassy parade ground??! Yet if the Brigantian tribesmen who lived on these hillsides looked down into the valley in life, they also looked up to the tops of the hills when faced with death. For it was here, on the high moorland ridges that their bodies were cremated and their ashes immured in windswept cairns and lonely burial mounds, destined to stand out as landmarks for peoples yet to settle in these upland fastnesses. The ancient Cleveland 'Lyke Wake Dirge' suggests a tradition of belief in transmigration after death, the conviction that the souls of the dead travelled over the hills to some distant, unknown 'otherworld'. In later, christianised times, the bodies of witches and the unbaptised were frequently buried at crossroads, again suggestive of a belief in some mysterious 'spiritual migration' along 'ways accursed'. Crossroads, landmarks, all these things are suggestive of 'leys', and there are many who would suggest that these urn burials were intended to take advantage of the 'earth currents', natural or otherwise. Equally there are many who would dismiss such ideas as 'bunk'. I prefer to keep an open mind.

Pinhaw Beacon was almost certainly one of these early burial cairns. 'Haw' is a variation of 'How' or 'Howe', a name always associated with hilltop cairns and burial mounds. Long, long ago some ancient local dignitary was buried here beneath a pile of stones, and the place has been a landmark ever since.

As to when Pinhaw first came to be used as a beacon site I am not wholly certain. Certainly it was manned to warn of the threatened invasion of Napoleon, and on a wild, wintry day in January 1805, there were to be tragic consequences as a result. At this time Pinhaw had six guards appointed to man the 'invasion beacon'. In pairs they stood sentinel over this lonely spot in weekly shifts, Elslack, Carleton and Lothersdale each sending up their two guards on a rota basis. A hut was built on the summit of the hill for the two guards to shelter in, and at the start of that fateful year, Lothersdale and Carleton having done their 'stints', Elslack dutifully sent up their two replacement men to man the beacon. One of these was a man called Robert Wilson. For some undisclosed reason the guard post ran out of provisions before the week was up, and Wilson decided to go down to Elslack for fresh supplies. The weather looked grim and was threatening snow, but Wilson saw no reason to worry about this and set off briskly down the moor. In Elslack he secured the much needed rations and set off back up the hill to the beacon. He was never seen alive again.

At the end of the week, Lothersdale sent up its two replacements as usual. After struggling through blinding snow and deep drifts they finally reached the guard post only to find Wilson's partner freezing, starving and raving deliriously. After regaling him with hot drinks, food and blankets he told them of how Wilson had left the hut some days before. After taking the revived guard down to Elslack his rescuers discovered that Wilson had left Elslack long ago, and now it suddenly dawned on them that Wilson was missing on the moors. A large scale search was immediately organised, and it was one of the search party, Jerry Aldersley from Calf Edge, who found Wilson's body in a little hollow, frozen to death, the provisions still at his side! His body was found little more than 150 yards from the hut. A memorial was erected on the spot where he was found, with the inscription:-

"Here was found the body of Robert Wilson, one of the beacon guards, who died January 29th 1805 aged 59 years...."

It is reputed that a head was originally carved on the stone, but if so,it can no longer be seen.

From Pinhaw Beacon the Pennine Way (heading south!) leads down into Lothersdale, although our route branches off before it gets there. Soon, moorland gives way to upland pasture, and as you negotiate the various stiles on the path, it might be wise to passthrough them carefully, especially in view of the ghastly story I am now about to relate........

According to local tradition, one of these upland pastures on the Lothersdale flanks of Pinhaw Beacon bears the unusual name of 'Swine Harrie'. The story goes that 'Swine Harrie' was crossing this field in the dead of night with a pig he had stolen from a nearby farmstead. The pig was tethered to a piece of rope, which was tied in a noose at the thief's end. Still leading the pig on the rope the thief, who was a heavy, burly man, suddenly found his way barred by a ladder stile (no doubt with 'P.W.' carved on it!). Not being very well endowed with brains, 'Swine Harrie' thereupon put the rope around his neck in order to free his hands to climb the stile. On reaching the topmost step he slipped, and hurtled over the other side of the wall. The weight of the pig pulled the rope taut, and the knavish 'Swine Harrie' duly met a just end at the hands (or should I say trotters?) of the animal he had stolen! Bearing this in mind, I would advise you to take care, and if you must take a dog on your rambles, make sure that it's a Jack Russell rather than a Great Dane!

Where the Pennine Way turns right down to Lothersdale the Beacons Way continues onwards past the boggy headwaters of the Stansfield Beck, following a weed choked lane up to Tow Top. Across a field and we enter Babyhouse Lane, where an interesting old milestone serves as a gatestoop in the wall to the right. Carved ' To Kighley 5 miles' it seems quite out of place, and one is inclined to wonder if it was moved to its present spot. Babyhouse Lane continues on down to Four Lane Ends, but before reaching it, earthworks may be seen in the field to the left, just above the plantation. This 'circular camp' is certainly ancient, and according to Speight, Danish, although I am inclined to think that it is more likely to be contemporary with the other ancient earthworks we mentioned earlier. Perhaps modern archaeology has since found the answer.

At Four Lane Ends we turn left towards Cononley. According to legend, there was once a gibbet here at this ancient crossroads. 12 felons were reputedly hanged, their bodies being buried by the roadside. It is said that the last man to be gibbetted here was a horse thief named Singleton, some time at the beginning of the 19th century. Be that as it may, this story, apocryphal or not, has echoes of old pagan practices and beliefs. It was not for nothing that a 'Pentitential' from the time of Egbert said that "any woman who would cure her infant by any sorcery, or shall have it drawn through the earth at the crossroads, is to fast for three years, for this is great paganism." Was not Odin the patron of the crossroads and the gallows? The Norsemen who settled in the northern dales also had their 'Nikkr', a fiddle playing demon, who endowed viking youth with the gift of music. This pagan spirit is the origin of the old north country belief that if you play a fiddle at a crossroads on a moonlit night you are likely to conjure up 'Owd Nick'. Ultimately, of course, such stories lend strength to the arguments of the 'leyhunters'.

Not far beyond Four Lane Ends, we come to, what is for me at any rate, one of the main attractions of the journey. Down a farm road to the right lies an arid wasteland, quite devoid of vegetation and topped by the quite incongruous apparition of a Cornish engine house! This is the Cononley Lead Mine, which, even as lead mines go, is unusual, being quite out of place in these Airedale uplands, a lone refugee from the spoil heap wastelands of Greenhow, Grassington Moor and Upper Swaledale, where such landscapes tend to be the norm rather than the exception.

The 'raison d'etre' for this industrial oddity, is, of course, a geological one. A single large mineral vein occurs here, being part of a major fault across what is known as the Bradley Anticline. The area was first exploited for its lead ores in the 16th and 17th centuries, and bell pits from this period still survive. The vein was part of the royalty of the Duke of Devonshire and in the 18th century miners were sent here from the Duke's workings on Grassington Moor, in order to try and develop the area's potential. It was not until 1830 however, before the mines began to be fully developed by Stephen Eddy, the Duke's Agent. A level was driven from the side of nearby Nethergill, and this exploratory working, known as Brigg's Level, discovered large quantities of cerrusite, a very soft, easily worked carbonate of lead. From here the mine developed apace and a smelt mill was constructed down the Gill, near Cononley. More levels were driven, Deep Level Crosscut cutting the vein at 205 fathoms. (1230 feet). A main shaft and an incline shaft were sunk and the whole area became a bustling hive of activity. Between 1830 and 1876, when the mine finally closed, it produced some 15000 tons of lead ore. The impressive engine house, more reminiscent of North Cornwall than West Yorkshire served the main shaft, which lies just behind it, capped by a steel grille. The building was lovingly restored by the Earby Mines Group, whose museum we didn't get much chance to see back in Earby.

For me, these old mines have an endless fascination, representing a technology and industrial culture quite apart from that associated with coal mining. It is hardly surprising that the engine house at Cononley looks like a refugee from Redruth - it probably was! Cornish miners were brought to the Dales to work the lead veins, and with them came Cornish techniques and 'know-how'. The tinners also brought their superstitions and beliefs:- 'spriggans','knockers' and all the other elemental subterranean creatures so beloved of the vivid Celtic imagination. Ad to them stories of 'phantom shifts' and ''t'owd men' and we enter the realms of an industry endowed not only with unique methods but also with a unique folklore.

Old lead mines can be eerie places. My first encounter with them was walking from Coast-to-Coast in 1973, which entailed traversing the great lead mined wasteland to the north of the Swale. Later forays took me to Grassington Moor, to Buckden Gill, to the remains of Wiseman's Level near Kettlewell. Some years later, at Trevaunance Cove on the North Cornwall Coastal Path I was amazed to discover 'Swinnergill - on -sea, and suddenly became aware of the similarities between the two mining areas.

It was with Keith Hannam, an experienced veteran caver, that I had my first experience of the 'innards' of some of these old workings:- exploring an adit level near Starbotton, and descending an inclined shaft near Trollers Gill, Skyreholme. I would not advise anyone to undertake such journeys lightly. Specialised equipment, and experienced, knowledgeable companions are not only necessary but vital. It is well known that caves can be dangerous, yet old mines, being man-made are doubly so. Never, ever, enter old mine workings out of mere passing curiosity. It could be the last thing you ever do, for beyond those inviting looking walled entrances lurk death traps galore:- loose earth and boulders shored up by rotting timbers, unexpected (and often flooded) internal shafts and unstable stopes.(Stopes are particularly dangerous - the miners left their gangue - spar and waste materials - piled up on tiered platforms shored up with timbers. The dangers posed by such structures after years of decay and and neglect should be palpably and appallingly obvious.) The moral is simple - KEEP OUT!!

Yet having said this, no-one can deny that old mines fascinate and stimulate curiosity. In your imagination at least, you can venture down old shafts and explore below in perfect safety! The 'underground' beckons, and if you feel you really need to see the 'insides' for real, there are societies you can join, and site museums you can visit. At Wendron, in Cornwall you can don a hard hat, fasten on a cap lamp and explore the interior of a fully renovated tin mine, a living, working museum, where the methods used by metalliferous miners, ancient and modern, are on show for all to see.

The 'working industrial museum' concept is at present, 'state-of-the-art' in the interpretation of our industrial and social past. It is not for me to discuss the merits of Beamish, the Crich Tramway Museum, the National Coal Mining Museum at Caphouse Colliery, near Wakefield and a host of other similar 'working' attractions to be seen all over the country. These places sell themselves, for they give not only a fascinating insight into the past but are also profitable tourist attractions into the bargain.

It seems sad to me that the Pennine lead mining industry, which wrote so much of the history of the Yorkshire Dales and made such a big impact in the shaping of its landscape has no such 'living monument' to its former greatness. The Earby Mines Museum, for all its praiseworthy acheivements, does not effectively rise to this challenge. There is a need for a WORKING lead mining museum, and what better place to site one than here, at Cononley Lead Mine? The site is not far removed from urban centres, and, unlike many of the Dales mines, it is easily reached by car and there is scope for developing parking facilities. Its surface remains are still dramatic, and having both shaft and incline access to the underground workings Cononley could offer great potential for underground tours for members of the public. The mine could be restored, the engine house fully restored, complete with steam engine and shaft headgear. Underground displays could depict the fascinating and often harsh life of the lead miner, and the 'on-the-surface processes of the industry could be housed in a complex of traditional wooden 'shafthead' buildings. Such a process would involve both the outlay of both money and vision in large quantities, factors which seldom go hand-in-hand in our modern, cynical world. Still, I can dream cant I??

Beyond Cononley Lead Mine our route winds around the pastures of Cononley Gib before finally descending to Cononley Village and the end od SECTION 2.

Cononley Gib, crowned with its mine chimney, and scarred by the occasional old working, is a pleasnt spot, giving fine views across the Upper Aire Valley. Particularly to the hills beyond Skipton and to the woodlands and rocks across the way, topped by the distinctive white 'pepperpot' of Kildwick Cross. It is a place of rising valley sounds and bleating sheep.

Cononley is an interesting little village. In Domesday it appears as 'Cutnelai' the property of one 'Torchil'. According to Speight the name means 'Canutes Field'. In the Middle Ages lands were held here by both the knights of St. John and the canons of Bolton Priory. The chiefest building of interest in the village is Cononley Hall, a rambling hybrid of architectural styles, being basically a three storeyed georgian mansion grafted onto a 16th century mullioned manor house. Cononley Hall was the traditional seat of the Swire Family, and a stone on the south wall is carved:-

S. E. S.

R. 1683 S

These initials stand for Samuel and Elizabeth Swire, and their son Roger Swire, who died in 1705.

Lead mines apart, Cononley's main industry has always been textiles. Baines' 1822 Directory list amongst the inhabitants of Cononley one Reuben Stansfield, a cotton manufacturer. Also Club Row, a long line of houses conspicuous from the railway were built specifically for the purpose of handloom weaving, being suitably lighted with 'weaving windows' on the upper storeys.

Cononley's beck runs through the heart of the village, eventually pouring into the Aire, not far beyond the railway. Buses to Keighley and Skipton alight at the Post Office, and Cononley's spick-and-span little railway halt gives acces to Morecambe, Lancaster, Bradford and Leeds. For such a little backwater of a village, Cononley seems to be remarkably well served by public transport.

Perhaps it was this easy access to places remote which stimulated the events of Tuesday 23rd January 1886, when the supporters of illegal gaming activities descended upon this sleepy place in great numbers. In those days the lonely moorlands of the Pennines were seen as the ideal location for illegal practices like gambling schools, dog fighting, cock fighting and last, but by no means least, the noble (and illegal) art of bareknuckle pugilism. The advantage of the moors for such gatherings was, (and in some places still is!) their isolation and solitude, it being easy for specially posted lookouts to give good advance warning of the approach of the 'enemy' i.e.- police constables and magistrates.

At 7am on this particular morning in 1886 the Leeds train clanked to a halt at a sleepy and unsuspecting Cononley. From the carriages emerged a host of motley looking individuals whom the local press later described as being "a select assortment of those species of the genus Homo, known in the parlance of certain papers as 'roughs', 'pugs', and 'sporting characters'." This gathering, reputedly some 200 strong and swelled by numerous locals no doubt intent upon 'seeing a fight', made its way up to Cononley Moor, to a place not far from the lead mine; and it was here that Teddy Curley and Tom Parfitt set out to 'do their utmost to maim, lame and mutilate each other in cool blood and friendly spirit' for the purpose of winning a nice, fat prze fighter's purse. Of course when the authorities got wind of what was going on they immediately sent three constables and a superintendent from Skipton, who arrived at Cononley Moor to find the fight over and the crowd dispersing. The constables gave chase to two men who were making off with the ropes and stakes which had been usesd for the ring, but, dropping their tackle, they managed to successfully make their escape. The stakes and rope were taken by police to Skipton, where they were valued at £20. No further such 'fight trains' were recorded. Today, Cononley seems as sleepy as ever, nestling in its hills and dreaming of days gone by..............

BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE

Copyright Jim Jarratt. 2006

Blacko Cross, a stone of uncertain antiquity, stands just beyond a gate at the side of the road. From here, a route leads along the wallside to Blacko Tower, but the fastened gate, the barbed wire and warning notice make it abundantly clear that your presence is not desired in these domains. So, suitably daunted, you turn right down the road towards Blacko, picking up a stile and 'FP' sign on the left, from which a path leads over fields to mud and barking dogs at Brownley Park. At Blacko Hillside, the next farm on, a choice must be made. An indistinct path on the left leads up the hillside past hawthorns and a gully to a wall stile, from which a left turn leads directly to Blacko Tower. The alternative is to continue onwards to Malkin Tower Farm (although you can backtrack from near Green Bank and see both if you have the energy). The choice is yours!

Blacko Tower is a curious place. Blacko means 'Black Hill', the 'o' part being simply a corruption of the better know 'haw' or 'how', a name frequently encountered on hilltop sites, usually in association with barrows and tumuli. No doubt in times long ago this lonely hill also would have possessed its prehistoric burial cairn. Standing at 1,108 feet above sea level, its view is nowhere near as impressive as that from Pendle Beacon, but it is not bad all the same.

Blacko Tower (also known as 'Stansfield Tower'), was built around 1890 by one Jonathan Stansfield, a local grocer who according to legend hoped to see over into Ribblesdale from it, only to find that it was not high enough and he was left with a useless folly. One day in 1964 the sun rose over the hills to disclose a tower that had been mysteriously whitewashed during the night! Who did it? And Why?? The culprits were never found and the mystery remains.

The area round Blacko Tower seems to court mysteries. Many years ago a bronze age axehead was found near here, implying that this hillside had significance to people who lived here long before the age of eccentric Lancashire grocers! I recall once driving home from Morecambe on a summer evening and passing this way, having followed a route through nearby Gisburn. The sun was low in the sky and rooks were circling the tower. It seemed to me a magical, haunted place, faintly reminiscent of Glastonbury Tor... a perfect place for a gathering of witches! Certainly people have some strange ideas about the place:- according to author Guy Ragland Phillips Blacko Tower is a nodal point (ie meeting place) of numerous mysterious 'ley' alignments. Far be it from me to either confirm or refute this assertion, 'leys' always having been a subject of potential controversy among archaeologists and antiquarians.

These mysterious 'straight track' alignments were first 'discovered' bt Alfred Watkins, a Herefordshire brewers representative and keen amateur antiquarian, who, on 30th June 1921, saw in an inspired flash of vision that churches, ancient boundary stones, ponds, beacons, holy wells, mounds, tumuli, wayside crosses, crossroads and a host of other landmarks could often be interlinked, being sited along straight, invisible alignments criss- crossing the landscapes of Britain. These alignments he called 'leys', and in his book, 'The Old Straight Track', Watkins went on to reveal a whole network of ancient 'straight tracks', forming, what for him was a simple and ingenious system of prehistoric road communication. 'The Old Straight Track' is well reasoned, plausible and makes a great deal of sense, and to read it without other information is to be 'converted'. However, Watkins' theories were (and still are!) frowned upon by the archaeological establishment; and with good reason, for while archaeologists will concede that straight alignments between prehistoric sites can and frequently do exist, they will not subscribe to Watkins' 'ley networks' on the grounds that his 'ley identification' criteria are unscientific. Their main argument is that the sites which characterise leys seldom, if ever, belong to the same historical periods. Of course the counter arguments to this are the evidences of folklore and the 'christianisation' and continual re-using of significant and sacred sites. The early Church, it is well known, managed to 'convert' a staunchly heathen Britain to Christianity in less than a century, but yet the real truth is that the conversion was often more apparent than real and had been achieved by compromise rather than by the awesome power of the Gospels. Pagan practices were, in fact, to prove a headache to Christian clerics for many centuries to come.

Yet ironically it is not the arguments of the archaeologists which confound Watkins' 'Straight Track' theories, but the subsequent discoveries of the 'Ley Hunters' themselves! Years of surveying and exploration using Watkins' own identification formula have uncovered a vast network of leys so numerous, and running so closely together, that whatever their purpose, they could never have been ancient trackways! Suddenly we have left the sober world of archaeology behind and entered the rather 'headier' realms of the paranormal.

So, assuming that there is more to leys than people drawing random straight lines on maps, what are we left with? Geomancy, dragon lore, dowsing, witchcraft, UFO sightings and all manner of 'psychic phenomena' have been associated with leys at one time or another. Of these, perhaps the most compelling is the assertion that leys are connected with some kind of magnetic force lines in the earth's crust. Certainly the Earth is a magnet, and so physical laws dictate that such forces should exist. Dowsers definitely seem to think so, and their repeated experiments at ancient sites have revealed a strange connection between the 'ley networks' and these mysterious 'earth currents'. Whether or not such 'forces' exist, must, of course, remain a subject of controversy. Dowsers often ascribe their ability to find water to their sensitivity to these mysterious 'earth forces'; but why?? Fantastic? Fanciful? I do not preseume to know. I do know, however, that dowsing WORKS.

Does Blacko Tower lie at the heart of a web of mysterious pseudo-magical forces? I don't know. I certainly didn't feel them when I was there, but then psychic powers were never my strong point! I wonder if Stansfield was aware of any such 'vibrations' when he built his tower? On the datestone is the biblical reference PS 127 VI. The Psalm to which this refers is well known:-

"Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it,

Except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain...."

So was Blacko Tower built to satisfy the eccentric whims of a Lancashire grocer, or was there a more subtle purpose behind its construction? Was it perhaps an attempt to 'christianize' a pagan site - a sort of victorian Paulinus cross? If the legend be true poor Stansfield must have laboured 'in vain'. For he never managed to see over into Ribblesdale and the Devil (presumably) took his tower!

Our next port-of-call is Malkin Tower Farm. Here, (you might be forgiven for thinking) is where the Pendle Witches held that fateful 'gathering of the clans' on Good Friday 1612. Unfortunately, what we would like to believe is often untrue, as the actual location for THE Malkin Tower is, in fact, one of the great mysteries of the Pendle 'Witch Country'. Various excavations have in fact been undertaken to try and find it, without success. Knowing the social status of the 'Demdikes' it was unlikely to have been a structure of much significance, being probably little more than a draughty stone hut. Various places have been suggested for its true location. Walter Bennett maintains that it stood in 'Malkin Field' at Sadler's Farm, Newchurch-in-Pendle. Other people are equally convinced that it lay somewhere between Blacko and Newchurch, or further afield, to the north. In 'Macbeth' one of the witches refers to her familiar as 'Greymalkin' - a cat, but deeper research would suggest that the word 'Malkin' means 'a scarecrow' or simply 'untidy'. It is sometimes encountered as a surname.

Certainly if the witches ever did meet here, in the vicinity of Malkin Tower Farm, then the visualization of this event must be left not to my dull scribblings, but to the imaginations of you, my readers. Just beyond Malkin Tower Farm, where the path turns left up the hill, there is a section of masonry wall which does not conform to the rules of drystone wall construction. Here, (in my imagination at least) lie the remains of 'Malkin Tower'.

Now at last the influence of Pendle Hill is truly receding and new pastures loom ahead. Beyond Peel's House, and the Old Gisburn Road, the route becomes a fine upland promenade along a walled track (Lister Well Road) which leads over some grand shooting moors before finally descending towards Barnoldswick. The views which predominate here are not of Pendle, but of the Yorkshire Dales and the 'Three Peaks' country, a distinctively 'Craven' landscape. Closer at hand is the country around the 'Aire Gap', and soon, to the right, our next objective, Pinhaw Beacon, comes into view. (The adjacent TV booster mast does tend to 'steal the scene' however, Pinhaw itself not being one of the most commanding of eminences.

Finally descending to the valley the Beacons Way just misses the outskirts of Barnoldswick (pronounced - 'Barlick') and briefly joins the Leeds and Liverpool Canal at Park Bridge.