THE BEACONS WAY

SECTION 3.

Cononley to Addingham

""By the hill and the dale and the standing stones,

By the buried urn with the calcined bones,

By the route the birds take on the wing,

By the horned cross, the cup, the ring....

The Pathfinder 1975

Leaving Cononley we cross the River Aire by a relatively modern bridge inscribed with the words:- 'K Holst and Co. 1928'. Now, at last, we are indisputably in Yorkshire and the crossing of the Aire is a significant milestone in the progress of our journey.

It would not be too wise to celebrate however, until you have got to the far side of the busy A629 road and are safely esconced upon the towpath of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. The road here is a veritable racetrack and crossing it in safety involves clutching protective talismans and uttering incantations for a safe passage!

Safe at last on the canal, a quite different world is now entered, of gently lapping waters, willowherb and rank, sweating butterbur. Swarms of insects skim the gentle waters and some of them bite! There is a lush, deep solitude, broken only by the chugging passage of the occasional boat, or an encounter with the odd angler. Enjoying this tranquillity we proceed all the way round to Kildwick, passing a couple of swing bridges en route. (Note the milestone on the left:- 'Leeds 25 and a half miles, Liverpool 102 miles.')

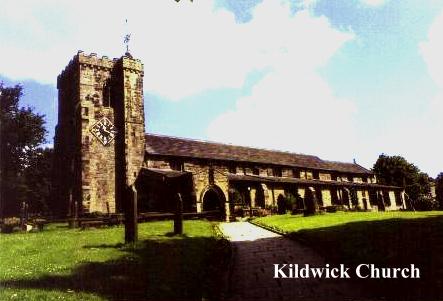

KILDWICK is a delightful village, and our approach to it, along the towpath, is superb to say the least. Do, please, resist the temptation to follow the canal all the way round to Silsden without interruption, for to stop off here and take a look around the village is not only desirable but a MUST!

Leaving the canal at Bridge number 186, you will be surprised to discover that with the churchyard to the south and the lych gate and cemetery to the north of the canal, this bridge is very much the churches' own private access, the canal, in a sense, running right through the churchyard! From the bridge, ascend the steps, and passing the Old School turn left to the Church. Pass around the front of the tower, noting its fine sundial and then go down the front path to the bottom gate, where steps lead down past the village stocks to the A629, and the heart of the village.

How that heart has changed! Kildwick now, after years of heavy traffic thundering over its ancient bridge, has been left high and dry by a complete section of the Aire Valley Trunk Road. When I passed this way it was within a couple of days of the new road being opened and I was stunned to find the place so peaceful! It was like a ghost town, with the roar of the traffic gone forever! As a result, for better or for worse, Kildwick has now lost its old identity and simply stares sullenly at the river, as if saying 'what now?!' Left alone with its memories or facing some unknown future, Kildwick is still deciding which way to turn. Whichever way that might be, let us hope that in the long run the change will be something more meaningful than just a speculative increase in the price of local property.

I will start my perambulation at Kildwick Bridge and gradually work back to the canal. Spanning the Aire, and now mercifully spared the grime of the commercial (and latterly works) traffic which has pounded over it for so long, Kildwick Bridge is without a doubt the oldest bridge in the Aire Valley. Although widened in 1780, the older part of the bridge is still fundamentally that which was built by the Canons of Bolton Priory in the 14th century. An entry in their account book, dating from 1305, reads:- 'In the building of the bridge of Kildwyk £21.12s 9d.' This work is characterised by the mediaeval ribbed understructure and fine masons marks, which I recall first seeing as child on a visit with the old Bradford Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group.

Retracing our steps to the village, let us take a well earned drink at the White Lion and discuss some of Kildwick's early history. In Saxon times this place was known as 'Childeuuic', and, according to Domesday was the property of an english owner by the name of Archil. After the conquest, the lands passed to the powerful De Romille Family, and the church, village and manor were given by Cecilia De Romille to the Priory of Embsay (afterwards Bolton). Two Halifax men, Robert Wilkins and Thomas Drake obtained Kildwick at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the manor eventually passing to the Currer Family in the reign of Elizabeth, with which family Kildwick has been associated ever since. The Bronte sisters knew of the Currers of Kildwick, and Charlotte, who visited Kildwick as a governess, seems to have been so impressed with the name that she incorporated it into her pen name of 'Currer Bell'.

Anyway, before you get TOO carried away with the best bitter, let us cross the road and take a look at Kildwick Church. As I mentioned earlier, there are stocks at the side of the entrance gate. These were reputedly last used as late as 1860 and according to the parish records the old law of 1531, which was enacted for the public whipping of vagrants in the streets, was enforced here up to the Stuart period - no doubt as a deterrent to hikers! (Like I said, go easy on the bitter!)

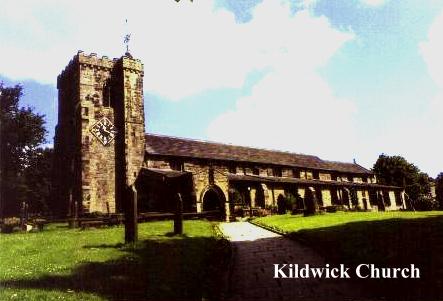

St. Andrew's Church, Kildwick, the 'Lang Kirk o' Craven', is 176 feet long by 48 and a half feet wide. The present church was rebuilt in the reign of Henry VIII, but contains much that is older. Its font is 15th century, and once was crowned by a carved oak canopy given by the Canons of Bolton, which was unhappily destroyed in the 19th century. Perhaps the oldest relics now preserved in the church are the fragments of six pre-norman crosses which were found built into the chancel wall during a restoration in 1901. These crosses originally stood on the south side of the church, and were used for building materials when the church was lengthened in the 15th century. They are believed to date from around 950 AD, or even earlier. Other relics of interest here include the Robert De Stiveton Monument of 1307, a 12th century memorial to a crusader, a letter to the people of Kildwick from Florence Nightingale and the famous 'Kildwick Cope', made from a bridal skirt belonging to the Imperial House of China. It was smuggled out of Peking in 1947 and presented to the church in 1959.

Kildwick Church also has, (you would expect so in a book like this) a connection with the Pendle witches. Dr. John Webster, the learned divine of Clitheroe, was in the early 17th century but a young curate here at Kildwick when he witnessed a 'witch discoverie' after evensong, when a great many local people were present.

The 'witchfinders', who had come to 'cleanse' the superstitious Kildwick congregation, were, in fact, the notorious Robinsons, among them the odious father-and-son team of the second Pendle witch trial, who had set themselves up in business as seekers out of witchcraft. After prayers, two of the Robinson family led in the 'boy that discovered witches'. Thereupon 'two unlikely men, his father and uncle, set him on a stool to look about him amid some disturbance.' (Which was soon followed with silent apprehension.)

Later, Webster tried to get to talk to the boy in private, but the Robinsons 'plucked the boy away.' Two 'able' justices they claimed, had believed unquestioningly in his testimony. It is not reported what happened as a result of this 'discoverie', but it is known that the Robinsons were 'doing the rounds' of churches and pointing out suspects, who, unable to prove their innocence or buy off their accusers were often faced with trial and punishment. 40 years later, Dr. Webster was to expose these practices in his 'Display of Witchcraft'.

Leaving Kildwick Church we enter the churchyard, and before retracing our steps to the school we should bear left from the tower in order to see the 'organ' monument in the lower churchyard. This novel gravestone, carved in the shape of an organ, marks the last resting place of John Laycock, who died on September 13th 1869 at the age of 81. The inscription below this novel sculpture informs us that 'the above is from the design of the first organ built by the said John Laycock.'

Retracing our steps to the church, a left turn leads out of the churchyard to the schoolhouse, and eventually back to the canal. An inscription there informs us that 'The School House was erected principally at the expense of the Revd. John Pering M.A., Vicar, aided by a grant from the National Society A.D. 1839.' There is a story that in 1840 a boy by the name of Feargus o' Connor Holmes attended the school, and the schoolmaster, (no doubt a tory opponent of chartism) refused to pronounce his christian name and simply referred to him as 'F'. (No doubt today he would have been dubbed 'Fergie'!)

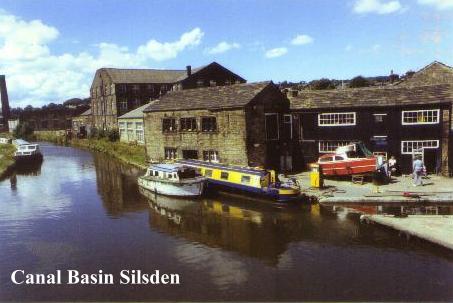

Regaining the canal, Kildwick soon falls behind as we strike determinedly onwards towards Silsden. There is a succession of swing bridges along this section of the canal, and being a 'veteran' of the 1988 Transpennine Canoe Marathon, each one is ingrained eternally upon my memory! Squeezing beneath one in kayak is not a pleasant experience:- while they may look to be a standard size and height above the water when viewed from the bank, the view from the waterline is decidedly different, and you are never quite certain as to whether or not you can pass beneath one until you are actually under the bridge, by which time your troubles have begun! At best you pop out of the other side covered in rust flakes and desperately trying to regain your balance! When I travelled through here in the summer of 1988 I was paddling in the wake of a Silsden pleasure boat which I fancied might open the bridges for me. I should have known better! The crew of the boat were drunk and it took them 30 minutes to get through the first bridge! The 'official bridge opener' kept falling in the cut! In disgust I paddled past them, resorting to the 'rusty squeeze' once more!

So far I have resisted saying anything much about the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. We first encountered it briefly on the other side of the Pennines near Barnoldswick, on its way to Liverpool and the Irish Sea. Here on the Airedale side, we have passed the summit pound and the waters here are bound for Leeds and ultimately the Humber. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal is a truly spectacular piece of engineering and has an interesting, if chequered, history. It is the longest single canal in Britain. 127 miles long, it climbs 487 feet through 92 locks between Office Lock in Leeds (where it is connected to the Aire and Calder Navigation for Goole and the Humber) and Stanley Dock in Liverpool. Branch arms of the canal once connected it with Bradford and Lancaster, and it is still connected to Manchester (via the Leigh Arm) and to Tarleton and the Ribble (via the Rufford Arm).

Although two thirds of the canal lie in Lancashire, it was fundamentally a Yorkshire idea, its headquarters being originally in Bradford. Its deviser and first Engineer, John Longbottom, was a Halifax man and Joseph Priestley, that 'Chief Engineer', whose 'able, zealous and assiduous attention to the interests of that great and important undertaking' ensured him an ornate memorial in Bradford Cathedral, where he slumbers beneath a carved relief depicting a canal boat emerging from the Foulridge Tunnel!

The first promoter of the canal was in fact a Bradford wool merchant named John Hustler. Well aware of the difficulties involved with transpennine transport (the only way across being by packhorse, an expensive mode of haulage), he was immediately sold on Longbottom's highly feasible idea of an east-west waterway which would take advantage of the low watershed between the Aire and the Ribble (the Aire Gap). Money was raised, and an Act of Parliament for the canal obtained in 1770. Construction work began immediately at both ends. Four years later, Liverpool was finally connected to Wigan, and after seven years work Skipton could be reached by boats from Leeds. At this point the bottom temporarily fell out of the venture and work became so sporadic that it was not until 1816, forty six years after the cutting of the first sod, that the canal was finally completed, amidst great celebrations. The Leeds and Liverpool was one of the most prosperous canals in the country, and showed profits right through into the railway Age. Even today, though no longer used for commercial carrying, it is one of the oldest and most successful recreational waterways in the country, its amenity value being recognised and exploited long before its transpennine rivals the Rochdale and the Huddersfield Narrow Canals, which have been restored only recently after years of what seemed irreversible neglect. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal is alive and kicking!

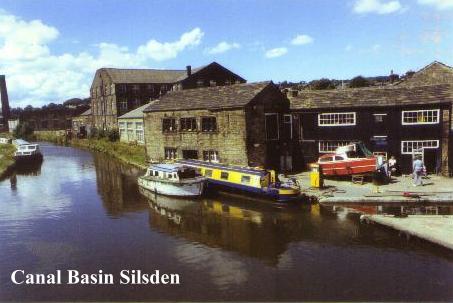

Soon the canal winds round to the right and houses and buildings begin to crowd in. A sign by the towpath welcomes us to Silsden, and invites us to 'stay awhile and enjoy the hospitality of Cobbydale'. It is a temptation hard to resist, for although lacking the rural charms of Kildwick, Silsden is endowed with other, more worldly assets like shops, pubs, chipshops, confectioners etc.

There certainly would have been no such 'mod.cons.' in Anglo-Saxon times when this place was known as 'Sighles Valley' or 'Dene'. In those days Silsden was held in 'feoff' to the Saxon Edwin Earl of Northumbria by five thanes, and after the Conquest it was, like Kildwick, given to the powerful De Romille Family, the five thanes remaining there as feudal tenants. Silsden also was part of the lands divided up by Cecilia De Romille around 1122, parts of it being given to the Canons of Bolton Priory. In later years, Silsden was to come under the sway of the mighty Cliffords of Skipton, the Skipton estates being granted to them by Edward II in 1310.

In 1513, the yeomen of Silsden, along with villages from most of the other settlements in the area accompanied old Henry Clifford, 'The Shepherd Lord', to Flodden Field where they helped to win a victory which ended for good the long endured depredations of the Scots in Northern England. The memory of these yeomen was enshrined on the 'Flodden Roll', which today is a treasure trove for genealogists. The mighty Cliffords though, did little towards the development of Silsden as a thriving community, for their continued ownership ensured that Silsden was never more than a small agricultural community, its farming supplemented by the odd bit of tanning and wool spinning. It was not, therefore, until the seventeenth century, when the impoverished Cliffords sold off much of their lands, that Silsden, newly 'liberated' began to establish a vigorous identity of its own.

The eighteenth century saw the establishment of two industries which were to characterise Silsden in later years:- linen weaving and nail making, thin ends of the 'wedge' of industrial revolution which was to eventually supplant cottage based industries and replace them with mills, machines and organised labour. Silsden alleges that it made the sailcloth for HMS Victory, but, as many other english communities claim this honour, it is wise not to be too confident of the assertion. It is true, though, that Silsden not only produced linen in vast quantities, but also grew the flax locally.

Silsden's nail making industry was established by a man from the Midlands by the name of William West, who came here in the eighteenth century. The industry flourished, the steel rods used being transported from Sheffield, no mean feat in those days! Because of this, Silsden was often referred to as being ' 't neck end o' Sheffield'. At the height of the industry's prosperity (around 1850), some 250 forges existed in and around the village, some employing workers and others being simply 'one man bands'. Local farmers set up nail making forges in sheds to supplement their meagre incomes.

Nail making was tedious and hard, and wages were poor, a journeyman nailmaker receiving 7d halfpenny per 1000 nails. The steel rods were forge heated, shaped with a hammer and placed on a fixed cutter, where sharp blows severed them into nails. Nailmaking by hand quickly declined of course with the development of nailmaking machinery, which made the forges obsolete. Not much distress was caused in Silsden by this however, as the decline in nailmaking happily co-incided with the arrival of an expanding textile industry, which offered more attractive employment in the new spinning mills and weaving sheds.

Only one nailmaker, William Driver, continued working effectively after the decline. He had brought in the new machines, and as a result of this was able to stay in business until 1930. At one point he had 40 employees, but with the closing down of his business Silsden's 'traditional industry' came to an end (although Silsden continued to make clog irons as late as 1950).

Silsden is a thriving town. In the heart of its bustle the beck tumbles over the little weir and children play on its banks. Having secured your refreshment you will now be heading back to the canal, and certainly not pausing to explore St. James' Church, which was originally constructed in 1712 out of a barn purchased for ten shillings from the Earl of Thanet. Neither are you likely to seek out Silsden 'Old Hall' which was built in 1682 on the site of an old Civil War arms depot. These and other curiosities await your exploration, but shortage of time will almost certainly deter any such efforts. Unfortunately we have deadlines to meet, so why not come back here another day? One thing for certain, Silsden isn't going to go away!

So once more on the towpath we continue on our way, braving the wrath of the occasional swan, until arrival at Brunthwaite Bridge. Crossing it, we leave the canal and follow the tarmac road up towards the golf club. A right turn, and the road eventually ascends the hillside towards trees, an excellent view of Airedale opening up behind us, with the two monuments on Earl Crag particularly prominent. (See the 'Watersheds Walk/Ivory Towers').

At the first bend, by a seat, the route takes to open country and continues up the right hand side of the gill, soon becoming a charming woodland path through deep bracken. After passing a little dell into which burst a charming cascade the route descends to a waterfall, above which the stream is crossed by a footbridge and a cobbled ford. (Large pipe adjacent). From here on an indistinct path ascends to Gill Grange, which, like many properties in the area, once belonged to the Canons of Bolton Priory.

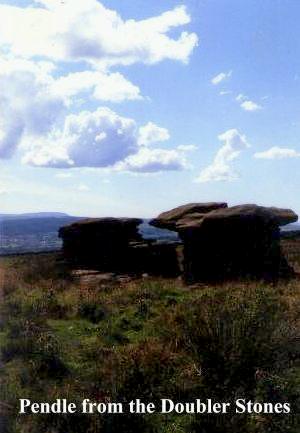

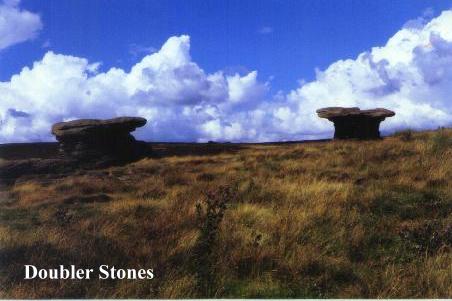

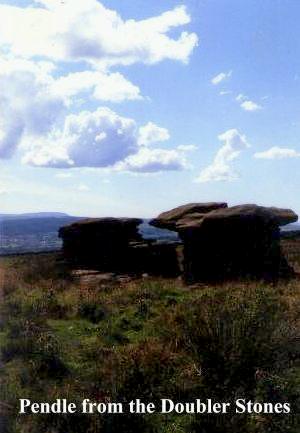

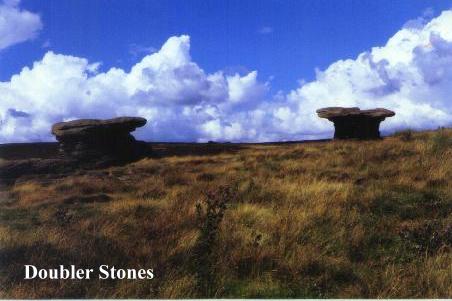

Beyond Gill Grange and a succession of tracks, the route winds round to Doubler Stones Farm and open moorland is reached at last. The strange, wind-worn rocks of the Doubler Stones are quite unmistakeable, and a left turn from the track, just before it winds round towards Black Pots, leads to them without complication, following the line of a low outcrop of rocks.

This is a good place for a refreshment stop. In wild conditions you can find shelter in the rocks. Here at Doubler Stones we are at the heart of a truly ancient landscape as the wild expanse of Rombald's Moor stretches away towards Rivock Edge. The moor is changing. Heather has given away to crowberry and crowberry to bracken. Like all such changes in the natural environment it is man made, being the end product of numerous successive moor fires. Another new feature in the landscape is the extensive afforestation which has been carried out around Rivock Edge. It was a source of surprise to me, having not travelled this way in many years, and my feelings about it were mixed to say the least. The loss of the heather has been a matter of some concern for many years, yet burying the landscape under a mass of closely packed conifers hardly seems to be a solution! Pine forests are both exclusive and intimidating, being a better deterrent to ramblers than razor wire and landmines! Once more it seems that when it comes to a choice between conservation and profitability, money (as usual) comes first.

According to legend, Rombald's Moor is named after a mighty giant who lived here long ago, and who has since gone downhill to nearby Keighley, where he now throws boulders at hapless passers by in the shopping mall! A more likely explanation suggests that the name is derived from the mighty Norman De Romille Family, who, as we have already seen, once owned virtually all the land in the area. What the name of the moor was in ancient times is anybody's guess, but one thing is certain:- it was frequented by peoples who lived long, long before the Norman Conquest. Indeed, when the Roman engineers built their road over the moors to the fort at Olicana (Ilkley), they would have seen landmarks which were old when the Roman Empire was young, for Rombald's Moor, being sited as it is, so close to the all-important Aire Gap, has long been a centre of prehistoric communication, trade and settlement. It is in fact, liberally sprinkled with minor antiquities:- cairns, enclosures and hut sites. There are also a number of stone circles, the most well known of these being the 'Twelve Apostles', which is still frequented by modern witch covens. The moors, with their contorted boulders, chalybeate springs, burial cairns and lonely, windswept ways were undoubtedly sacred in the minds of ancient peoples, who, being much more finely attuned to the rhythms of nature than modern man, were steeped in 'earth magic' and the worship of 'elemental gods'. This stark attunement is perhaps distantly echoed by the well known local song 'On Ilkla Moor Baht 'At', which, although comic, contains a universal religious idea :- the regenerative power of the earth - the fertility of the land.

The DOUBLER STONES consist of two 'mushroom' shaped rocks with layers of hard grit perched on pillars of softer, eroded sandstone.. Their name is derived from the old celtic 'dwbler' meaning 'dish'. No prehistoric man could visit such a dramatic site as this and be so unmoved as to shrug it off as mere 'wind erosion'. These enigmatic stones, gaunt, grotesque gargoyles of rock hugging this windswept moorland outcrop stand sphinx-like, stone tablets with pages lying open before dark scudding clouds - that cannot read!

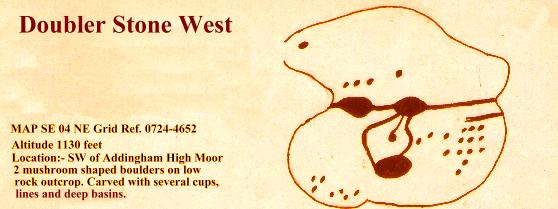

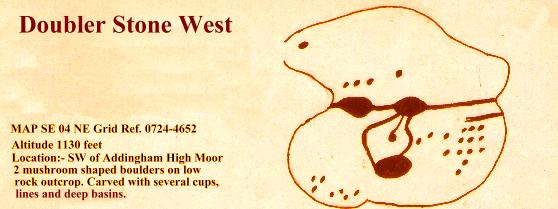

Yet perhaps WE can read some of these pages. Small, shadowy people of long ago certainly did, and, in places significant to them but not so obvious to us, they left their 'cup-and-ring' carvings, strange, mystical interfaces between earthly realities and the realms of the spirit world. The carvings here at Doubler Stones consist of two large incised cups on Doubler Stone East, and several cups, lines and deep basins on Doubler Stone West. None of the carvings are immediately obvious or apparent and must be searched for.

These carvings are by no means unique, and better examples exist elsewhere. Study a few detailed maps and you will see that they abound all over the area. The uplands between Aire and Washburn contain, in fact, the highest concentration of these carvings in the British Isles. Probe deeper, and they are found to be divided into four main groups or 'fields', the largest of these being Rombald's Moor itself, particularly along its northern edges. To the south, there is another group on Baildon Moor, and to the east a smaller group of carvings on Otley Chevin. Finally, an isolated (and significant) group is to be found on the moors above Washburndale, particularly in the vicinity of Snowden Moor. This 'field' is crossed by the BEACONS WAY and will be touched upon in SECTION 4.

Of course the most tantalising question of all is 'who carved these mysterious reliefs and why?' What on earth can they signify, these strange circles and depressions incised into remote boulders so long ago? Here is, of course, one of the great mysteries of prehistoric archaeology. Many, many, theories have been forwarded and many more will be. None of them are ever likely to provide a definitive answer.

Let us look at what we do know. It is generally agreed that the date of the carvings may be placed around what is loosely termed 'the Bronze Age' - although some examples have been dated as 'Iron Age'. It is also agreed that there seems to be a tenuous 'line of descent' from the strange spirals, zigzags and lozenges which are frequently found on the walls of Megalithic Passage Graves. Coming forward in time, the designs seem to be further echoed in the curious 'Troy Maze' designs - (a good example of which may found at Alkborough in South Humberside.) Normally the design is associated with turf mazes, but there are carved examples, like those in the Rocky Valley near Tintagel, Cornwall, which are identical in design to mazes depicted on Minoan coins from Knossos in Crete. Some people have commented that the cups and rings seem like staring eyes, and there may be some truth in this, as prehistoric 'Mother Goddess' representations have eyes which follow very similar artistic conventions. Perhaps most surprising of all is a similarity to certain aspects of Australian Aboriginal rock shelter art, some examples of which are known to have been executed in the last century!

From all this it is clear that the ideas behind the designs seem to transcend the boundaries of archaeological epoch, and, in a strange, mysterious way, seep through into modern consciousness. They come in different forms, and from different periods, yet always seem to incorporate the same, traditional shapes in the finished product. Indeed, have we not seen them already, on the ancient crosses which once proclaimed a new religion on Whalley's green sward? Can they not be seen in the vigorous and serpent-like designs so typical of the art of the Viking Age, an age when the followers of Christ were forced by circumstance to share an uneasy cohabitation with bleak, desolate gods which still beckoned men to the high places, to rocks, wells and standing stones? The Church might have held the promise of ultimate salvation, baptising people with water, yet high on the hills people might still hear the voices of the air and feel the cracks and tremors of the living earth! By a shepherd's fire, with smoke spiralling from flickering flames, men might still invoke serpents and hear the roar of the dragon.

In later times, when these gods were little more than a dark memory, holed stones were carried as a defence against witchcraft. 'Eyes of God' were carved on churches for much the same reasons. In the 'like begets like' tradition of ritual magic, the power of 'the stones' had at last been overcome...... by the power of stones!!

Prehistoric standing stones, though man-made, are definitely about art imitating nature. The stones were intended to blend into a landscape in a way that harmonized them with it, making them a part of it. Such megaliths tend to be in short supply in the High Pennines, the implication being that the population was too sparse, or that later developments obliterated what few there were, sometimes converting them into boundary stones or wayside crosses.

Be that as it may, it would seem that the main reason for the paucity of Pennine 'standing stones' is a geological one. If megaliths are about art imitating nature, why go to the troble of constructing them, if nature can provide such sites 'ready made'? The moors, with their twisted rock outcrops, belaboured by the elements, are natural 'megaliths' and perhaps this might go some way towards explaining the profusion of ancient carvings, for surely a natural boulder that was held 'sacred' would have to be identified in some way, to in effect tell passers by that 'this stone has power', or is 'holy'. Whether or not this was the raison d'etre for cup-and- ring carvings is not for me to say, but the use of similar patterns in the christian crosses of later times, suggests there may be at least a grain of truth to this theory.

Of course there are many other theories!! Some people have suggested that the carvings are 'maps' of local village settlements. Aerial photography should, of course, verify such a theory. In practice it does not. On the other hand, there are people quite convinced that the carvings represent the spaceships of ancient extraterrestrials who landed here in prehistoric times! Between these extremes we are presented with a wide range of potential religious symbols and pseudo-scientific theories. Sun signs, moon signs, astronomical charts, stylised human faces have all been associated with the carvings. That the rock art has a symbolic nature seems fairly certain. Two of the designs, the Swastika Stone on Addingham High Moor and the Tree of Life Stone on Snowden Carr can both be positively identified with known ancient symbolism.

The Swastika Stone (which may be visited if you don't mind a two mile detour towards Ilkley) is especially of interest. Later in date than most of the other carvings, it is an unmistakeable 'fylfot' or 'sun wheel', the same symbol we encountered over the monks washing facilities in Whalley Abbey. This symbol was imported from the Middle East during the Iron Age, and is still commonly found today in the religious symbolism of the Indian Subcontinent. That is interesting enough, but of even greater significance is the style of the carving, as it is made up of incised cups and rings, which makes the symbol quite obviously the end product of an artistic evolution which has its origins in the older carvings. The Swastika Stone, like the later Celtic crosses, represents a new religious symbol executed in a 'traditional style'. It therefore seems logical that the older carvings too, are likely to be 'symbolic' in nature, being in turn descended from the older geometries of the Neolithic. The symbols change, but the style remains constant.

It is easy (too easy!) to dismiss cup-and-ring carvings as the awed scratchings of a bunch of primitive cavemen, yet such a hypothesis will not hold water! Truly primitive peoples, the nomadic hunter/gatherers of the Old Stone Age, have left us beautiful examples of representational cave art, which depicts their world with an amazing vitality. Surely it is rather naïve to assume that the well housed and well equipped hill farmers who lived much, much later in Bronze Age Yorkshire should be their cultural inferiors, incapable of sophisticated creative expression? The carvers of the cups lived in stable village communities which would certainly have had a hierarchical structure, no doubt including a 'shaman/witch/priestess' class. These people would have been the custodians of knowledge, both mundane and occult, and their rock art, far from being 'awed scratchings' represent a great step forward from the painted caves of Lascaux; a step from the depiction of the concrete world to the expression of the abstract. If the paintings of Lascaux and Altamira are comparable to 'old masters' then the cup-and-ring art represents its evolution into cubism, for the carvers of the rocks weren't interested in the 'real world' they looked to unseen (maybe even drugged!) realms, seeking to encapsulate symbolic meaning in abstract shapes. (Perhaps they saw the Doubler Stones as 'magic mushrooms!)

As I have already mentioned. There is a universality in the designs, which range from Australia to Arizona. The spiral, the lozenge, the cup and the eye-like concentric rings all seem to have a hidden meaning which stirs up the sediments of the unconscious mind and says:- why do you hesitate? You KNOW what I am! There is a sensation of depth in some of the carvings, the feeling of looking into a 'hypnotic vortex'. There is also a suggestion of fertility, the designs being evocative of leaves, droplets of water, the sun, the crescent moon, and sperms fertilising eggs. The images seem so familiar, yet are so stylised the defy accurate definition. Dowsers have associated the 'spiral force' with the mysterious 'earth currents' we mentioned earlier, and it is possible there was an element of geomancy associated with the carvings, that 'earth harmonising' which the Chinese refer to as Feng Shui.

The true purpose of the carvings will never, of course, be known. It could be that the designs represent a kind of 'proto-writing' a symbolic simplification of religious ideas, perhaps even allied to mathematical expression. The work of Professor Thom with prehistoric stone circles has already revealed the surprising mathematical aptitude of these vanished peoples. It seems fairly certain that they had a considerable store of astronomical knowledge and had not only discovered Pythagoras' Theorem in advance of Pythagoras, but had also discovered the value of Pi - an amazing acheivement!

The symbolic origins of writing are well known. Sea roving Vikings in the Dark Ages, camping out in ancient tombs would carve their runic inscriptions alongside the whirling spirals of their long vanished builders. Viking runes were real letters, a proto alphabet spelling out identifiable messages which may still be read today, (usually ' Kilwulf was here!') But yet each rune had its own, sacred, hidden meaning, the characters being both phonetic letters and abstract religious symbols at the same time. Were they perhaps, the end product of what began with the cups and rings? (Scandinavia too, has its cup-and-ring carvings).

In the light of these magical roots of our everyday writing, could it be that underlying the cups and rings is a deeper yet far simpler meaning? When we doodle - scribble absent mindedly, we let our unconscious minds do the work, aimlessly stringing shapes and patterns together without any obvious meaning. There are persons who claim that they can analyse a persons character from their doodles! I would love to see what they might make of the 'doodles' on Rombald's Moor! I say this, for if you examine most peoples automatic drawings you will discover concentric rings, spirals, lozenges and zig zags, all the contents in fact, of the Bronze Age sculptor's 'pattern book'! These designs have a basic universality, and seem to exist in the minds of humans irrespective of culture, country or level of civilisation. Perhaps the reason that we find the cups and the rings so strangely compelling is because we are a part of them and they part of us, the perfect unity between man and the natural world in which he lives.

Somehow, the carvings seem to be connected with the way we perceive the physical universe. We can 'see' these designs everywhere, in pool ripples, radio waves, microscopic organisms, minerals, atomic structures, stars and wheeling galactic spirals. The list is endless! Perhaps, in a way that is both intuitive and mathematical, the ancient stone carvers were able to symbolize the universality of form and mans physical and spiritual harmony with it. A genetic yardstick of the way we perceive things. As the carvings are a part of the stones, so are they a part of us. Their potency is simple yet quite profound. In harmony with the elements, the sun, the moon, the wind and the rain, these ancient people, wittingly or otherwise, managed to express something that had never been expressed before - the 'machine code' that defines the parameters of human perception!

Enough of theories! Let's pack the flasks and return to the business of walking THE BEACONS WAY. Ascending the moor by shooting butts we reach a stile in a wall, and not far beyond it, emerge onto Addingham Moor Edge, where a sudden and captivating view of Wharfedale opens up. Below us lies Addingham, at the end of Section Three, and opposite, across the valley, the massive bulk of Beamsley Beacon towers over Bolton Bridge, dominating the landscape. Now at last, you begin to feel that the end of our journey is finally in sight.

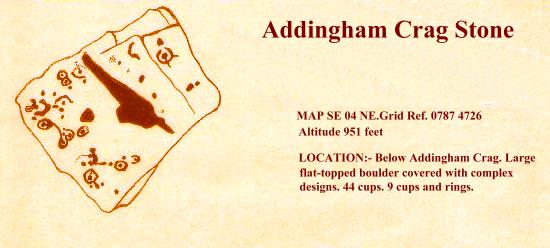

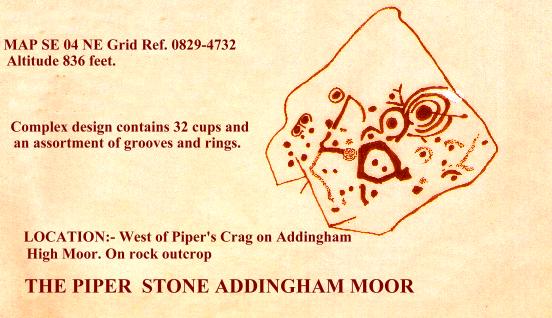

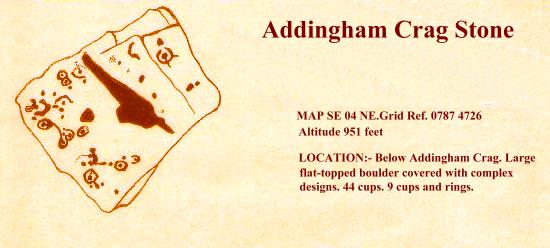

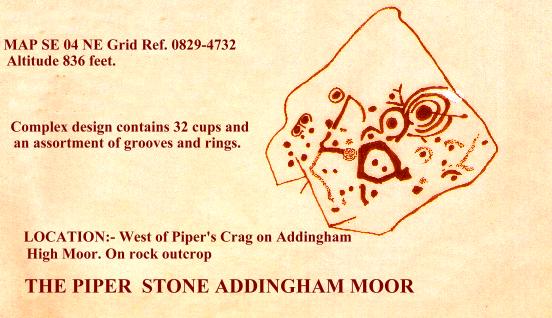

Addingham Moor Edge is home to a number of rock carvings, the most sophisticated of these being the Piper Stone and the Addingham Crag Stone (see illustrations). These stones are off-route and must be sought out. A right turn along the 'edge' leads to Heber's Ghyll and Ilkley via the Swastika Stone.

The main route however bears left, and brings you very quickly to Windgate Nick, a time honoured 'pass' through the edge which has been a landmark for many centuries, and could in fact, be man made, being possibly part of a prehistoric tackway. Whatever the case, its use as an old drover's road is in no doubt. The 'Gate' part of the name is not, as you might think, derived from 'barrier' but rather comes from the Norse 'gata' meaning 'road' or 'way'. It is, in fact, a name commonly associated with old packhorse and drove routes, and in old northern towns with streets. In days gone by, the drovers would drive their animals over the hills to be sold at the traditional fairs and markets of Northern England. Drovers from the famous Malham and Bordley Fairs would first come down to Skipton, and then, to avoid paying tolls on the newly opened turnpikes in the valleys, they would take to this ancient upland route, travelling from Cringles Top to Doubler Stones via Windgate Nick. From the Doubler Stones the old drove road led past Black Pots Farm, which was once an inn known as the 'Gaping Goose'. From here it led over the moor and the beck, eventually joining the Morton Road at Holden Gate. Now the drovers would proceed onwards to Bingley, the following day striking out for Bradford and the famous Wibsey Fair, where there was always a ready market for horses, cattle and geese. (The geese by the way, would have their feet tarred to enable them to undertake their 'long distance waddles' - sort of avian welly boots!)

Retracing our steps along the edge to the small cairn which lies in a hollow at a crossroads of paths, the main route passes through a gap in the rocky bastion and descends a steep boulder field in the direction of Addingham Moorside. As you climb over the stile in the wall, look behind you to the right. Below the crags in the boulder field just beyond the first descending wall, you will see a carved millstone, a lone relic of an industry which once flourished here on the moor edge. The millstone quarries were certainly in use in the second half of the seventeenth century, and it is quite likely that stone was quarried here at a much earlier date. The quarries lay within the boundaries of the Manor of Addingham, which in the 17th century was part of the estates of the influential and powerful Vavasour Family of Haslewood. The hard, granular gritstone of the moor edge was ideal for the manufacture of millstones to grind corn, and there was a universal demand for them, especially in areas where suitable stone was not locally available.

The Addingham quarries were apparently worked by a succession of leaseholders, the first to be mentioned being one John Wainman of Addingham, who worked the quarry from 1683 to 1711. The quarries were leased to him by a group of local landowners, who in turn seem to have acquired their rights from the Lord of the Manor. The rents obtained by these 'freeholders' were devoted to the relief of Addingham's poor. It is quite obvious that considerable amounts of material were hewn from these crags down the centuries and transporting the millstones downhill from the quarries must have presented serious logistical problems! The 'going' downhill to Addingham is quite steep, and the place is deceptively distant, as we are about to discover.

From Addingham Moorside the Beacons Way meanders down through pastures frequented by babbling becks and scurrying bunnies, eventually reaching tarmac at Small Banks, where there is a phone box. Passing through the stiles, the route crosses more fields, a disused (and barely noticeable) railway line, and finally emerges into Addingham's busy main road opposite the Fleece Inn. It will seem like an eternity since you left Addingham Moor Edge, but at least now you can relax a bit, for we have reached 'civilisation' once more. We have also reached the end of SECTION 3.!

BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE

Copyright Jim Jarratt. 2006

""By the hill and the dale and the standing stones,

By the buried urn with the calcined bones,

By the route the birds take on the wing,

By the horned cross, the cup, the ring....

The Pathfinder 1975

Leaving Cononley we cross the River Aire by a relatively modern bridge inscribed with the words:- 'K Holst and Co. 1928'. Now, at last, we are indisputably in Yorkshire and the crossing of the Aire is a significant milestone in the progress of our journey.

It would not be too wise to celebrate however, until you have got to the far side of the busy A629 road and are safely esconced upon the towpath of the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. The road here is a veritable racetrack and crossing it in safety involves clutching protective talismans and uttering incantations for a safe passage!

Safe at last on the canal, a quite different world is now entered, of gently lapping waters, willowherb and rank, sweating butterbur. Swarms of insects skim the gentle waters and some of them bite! There is a lush, deep solitude, broken only by the chugging passage of the occasional boat, or an encounter with the odd angler. Enjoying this tranquillity we proceed all the way round to Kildwick, passing a couple of swing bridges en route. (Note the milestone on the left:- 'Leeds 25 and a half miles, Liverpool 102 miles.')

KILDWICK is a delightful village, and our approach to it, along the towpath, is superb to say the least. Do, please, resist the temptation to follow the canal all the way round to Silsden without interruption, for to stop off here and take a look around the village is not only desirable but a MUST!

Leaving the canal at Bridge number 186, you will be surprised to discover that with the churchyard to the south and the lych gate and cemetery to the north of the canal, this bridge is very much the churches' own private access, the canal, in a sense, running right through the churchyard! From the bridge, ascend the steps, and passing the Old School turn left to the Church. Pass around the front of the tower, noting its fine sundial and then go down the front path to the bottom gate, where steps lead down past the village stocks to the A629, and the heart of the village.

How that heart has changed! Kildwick now, after years of heavy traffic thundering over its ancient bridge, has been left high and dry by a complete section of the Aire Valley Trunk Road. When I passed this way it was within a couple of days of the new road being opened and I was stunned to find the place so peaceful! It was like a ghost town, with the roar of the traffic gone forever! As a result, for better or for worse, Kildwick has now lost its old identity and simply stares sullenly at the river, as if saying 'what now?!' Left alone with its memories or facing some unknown future, Kildwick is still deciding which way to turn. Whichever way that might be, let us hope that in the long run the change will be something more meaningful than just a speculative increase in the price of local property.

I will start my perambulation at Kildwick Bridge and gradually work back to the canal. Spanning the Aire, and now mercifully spared the grime of the commercial (and latterly works) traffic which has pounded over it for so long, Kildwick Bridge is without a doubt the oldest bridge in the Aire Valley. Although widened in 1780, the older part of the bridge is still fundamentally that which was built by the Canons of Bolton Priory in the 14th century. An entry in their account book, dating from 1305, reads:- 'In the building of the bridge of Kildwyk £21.12s 9d.' This work is characterised by the mediaeval ribbed understructure and fine masons marks, which I recall first seeing as child on a visit with the old Bradford Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group.

Retracing our steps to the village, let us take a well earned drink at the White Lion and discuss some of Kildwick's early history. In Saxon times this place was known as 'Childeuuic', and, according to Domesday was the property of an english owner by the name of Archil. After the conquest, the lands passed to the powerful De Romille Family, and the church, village and manor were given by Cecilia De Romille to the Priory of Embsay (afterwards Bolton). Two Halifax men, Robert Wilkins and Thomas Drake obtained Kildwick at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the manor eventually passing to the Currer Family in the reign of Elizabeth, with which family Kildwick has been associated ever since. The Bronte sisters knew of the Currers of Kildwick, and Charlotte, who visited Kildwick as a governess, seems to have been so impressed with the name that she incorporated it into her pen name of 'Currer Bell'.

Anyway, before you get TOO carried away with the best bitter, let us cross the road and take a look at Kildwick Church. As I mentioned earlier, there are stocks at the side of the entrance gate. These were reputedly last used as late as 1860 and according to the parish records the old law of 1531, which was enacted for the public whipping of vagrants in the streets, was enforced here up to the Stuart period - no doubt as a deterrent to hikers! (Like I said, go easy on the bitter!)

St. Andrew's Church, Kildwick, the 'Lang Kirk o' Craven', is 176 feet long by 48 and a half feet wide. The present church was rebuilt in the reign of Henry VIII, but contains much that is older. Its font is 15th century, and once was crowned by a carved oak canopy given by the Canons of Bolton, which was unhappily destroyed in the 19th century. Perhaps the oldest relics now preserved in the church are the fragments of six pre-norman crosses which were found built into the chancel wall during a restoration in 1901. These crosses originally stood on the south side of the church, and were used for building materials when the church was lengthened in the 15th century. They are believed to date from around 950 AD, or even earlier. Other relics of interest here include the Robert De Stiveton Monument of 1307, a 12th century memorial to a crusader, a letter to the people of Kildwick from Florence Nightingale and the famous 'Kildwick Cope', made from a bridal skirt belonging to the Imperial House of China. It was smuggled out of Peking in 1947 and presented to the church in 1959.

Kildwick Church also has, (you would expect so in a book like this) a connection with the Pendle witches. Dr. John Webster, the learned divine of Clitheroe, was in the early 17th century but a young curate here at Kildwick when he witnessed a 'witch discoverie' after evensong, when a great many local people were present.

The 'witchfinders', who had come to 'cleanse' the superstitious Kildwick congregation, were, in fact, the notorious Robinsons, among them the odious father-and-son team of the second Pendle witch trial, who had set themselves up in business as seekers out of witchcraft. After prayers, two of the Robinson family led in the 'boy that discovered witches'. Thereupon 'two unlikely men, his father and uncle, set him on a stool to look about him amid some disturbance.' (Which was soon followed with silent apprehension.)

Later, Webster tried to get to talk to the boy in private, but the Robinsons 'plucked the boy away.' Two 'able' justices they claimed, had believed unquestioningly in his testimony. It is not reported what happened as a result of this 'discoverie', but it is known that the Robinsons were 'doing the rounds' of churches and pointing out suspects, who, unable to prove their innocence or buy off their accusers were often faced with trial and punishment. 40 years later, Dr. Webster was to expose these practices in his 'Display of Witchcraft'.

Leaving Kildwick Church we enter the churchyard, and before retracing our steps to the school we should bear left from the tower in order to see the 'organ' monument in the lower churchyard. This novel gravestone, carved in the shape of an organ, marks the last resting place of John Laycock, who died on September 13th 1869 at the age of 81. The inscription below this novel sculpture informs us that 'the above is from the design of the first organ built by the said John Laycock.'

Retracing our steps to the church, a left turn leads out of the churchyard to the schoolhouse, and eventually back to the canal. An inscription there informs us that 'The School House was erected principally at the expense of the Revd. John Pering M.A., Vicar, aided by a grant from the National Society A.D. 1839.' There is a story that in 1840 a boy by the name of Feargus o' Connor Holmes attended the school, and the schoolmaster, (no doubt a tory opponent of chartism) refused to pronounce his christian name and simply referred to him as 'F'. (No doubt today he would have been dubbed 'Fergie'!)

Regaining the canal, Kildwick soon falls behind as we strike determinedly onwards towards Silsden. There is a succession of swing bridges along this section of the canal, and being a 'veteran' of the 1988 Transpennine Canoe Marathon, each one is ingrained eternally upon my memory! Squeezing beneath one in kayak is not a pleasant experience:- while they may look to be a standard size and height above the water when viewed from the bank, the view from the waterline is decidedly different, and you are never quite certain as to whether or not you can pass beneath one until you are actually under the bridge, by which time your troubles have begun! At best you pop out of the other side covered in rust flakes and desperately trying to regain your balance! When I travelled through here in the summer of 1988 I was paddling in the wake of a Silsden pleasure boat which I fancied might open the bridges for me. I should have known better! The crew of the boat were drunk and it took them 30 minutes to get through the first bridge! The 'official bridge opener' kept falling in the cut! In disgust I paddled past them, resorting to the 'rusty squeeze' once more!

So far I have resisted saying anything much about the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. We first encountered it briefly on the other side of the Pennines near Barnoldswick, on its way to Liverpool and the Irish Sea. Here on the Airedale side, we have passed the summit pound and the waters here are bound for Leeds and ultimately the Humber. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal is a truly spectacular piece of engineering and has an interesting, if chequered, history. It is the longest single canal in Britain. 127 miles long, it climbs 487 feet through 92 locks between Office Lock in Leeds (where it is connected to the Aire and Calder Navigation for Goole and the Humber) and Stanley Dock in Liverpool. Branch arms of the canal once connected it with Bradford and Lancaster, and it is still connected to Manchester (via the Leigh Arm) and to Tarleton and the Ribble (via the Rufford Arm).

Although two thirds of the canal lie in Lancashire, it was fundamentally a Yorkshire idea, its headquarters being originally in Bradford. Its deviser and first Engineer, John Longbottom, was a Halifax man and Joseph Priestley, that 'Chief Engineer', whose 'able, zealous and assiduous attention to the interests of that great and important undertaking' ensured him an ornate memorial in Bradford Cathedral, where he slumbers beneath a carved relief depicting a canal boat emerging from the Foulridge Tunnel!

The first promoter of the canal was in fact a Bradford wool merchant named John Hustler. Well aware of the difficulties involved with transpennine transport (the only way across being by packhorse, an expensive mode of haulage), he was immediately sold on Longbottom's highly feasible idea of an east-west waterway which would take advantage of the low watershed between the Aire and the Ribble (the Aire Gap). Money was raised, and an Act of Parliament for the canal obtained in 1770. Construction work began immediately at both ends. Four years later, Liverpool was finally connected to Wigan, and after seven years work Skipton could be reached by boats from Leeds. At this point the bottom temporarily fell out of the venture and work became so sporadic that it was not until 1816, forty six years after the cutting of the first sod, that the canal was finally completed, amidst great celebrations. The Leeds and Liverpool was one of the most prosperous canals in the country, and showed profits right through into the railway Age. Even today, though no longer used for commercial carrying, it is one of the oldest and most successful recreational waterways in the country, its amenity value being recognised and exploited long before its transpennine rivals the Rochdale and the Huddersfield Narrow Canals, which have been restored only recently after years of what seemed irreversible neglect. The Leeds and Liverpool Canal is alive and kicking!

Soon the canal winds round to the right and houses and buildings begin to crowd in. A sign by the towpath welcomes us to Silsden, and invites us to 'stay awhile and enjoy the hospitality of Cobbydale'. It is a temptation hard to resist, for although lacking the rural charms of Kildwick, Silsden is endowed with other, more worldly assets like shops, pubs, chipshops, confectioners etc.

There certainly would have been no such 'mod.cons.' in Anglo-Saxon times when this place was known as 'Sighles Valley' or 'Dene'. In those days Silsden was held in 'feoff' to the Saxon Edwin Earl of Northumbria by five thanes, and after the Conquest it was, like Kildwick, given to the powerful De Romille Family, the five thanes remaining there as feudal tenants. Silsden also was part of the lands divided up by Cecilia De Romille around 1122, parts of it being given to the Canons of Bolton Priory. In later years, Silsden was to come under the sway of the mighty Cliffords of Skipton, the Skipton estates being granted to them by Edward II in 1310.

In 1513, the yeomen of Silsden, along with villages from most of the other settlements in the area accompanied old Henry Clifford, 'The Shepherd Lord', to Flodden Field where they helped to win a victory which ended for good the long endured depredations of the Scots in Northern England. The memory of these yeomen was enshrined on the 'Flodden Roll', which today is a treasure trove for genealogists. The mighty Cliffords though, did little towards the development of Silsden as a thriving community, for their continued ownership ensured that Silsden was never more than a small agricultural community, its farming supplemented by the odd bit of tanning and wool spinning. It was not, therefore, until the seventeenth century, when the impoverished Cliffords sold off much of their lands, that Silsden, newly 'liberated' began to establish a vigorous identity of its own.

The eighteenth century saw the establishment of two industries which were to characterise Silsden in later years:- linen weaving and nail making, thin ends of the 'wedge' of industrial revolution which was to eventually supplant cottage based industries and replace them with mills, machines and organised labour. Silsden alleges that it made the sailcloth for HMS Victory, but, as many other english communities claim this honour, it is wise not to be too confident of the assertion. It is true, though, that Silsden not only produced linen in vast quantities, but also grew the flax locally.

Silsden's nail making industry was established by a man from the Midlands by the name of William West, who came here in the eighteenth century. The industry flourished, the steel rods used being transported from Sheffield, no mean feat in those days! Because of this, Silsden was often referred to as being ' 't neck end o' Sheffield'. At the height of the industry's prosperity (around 1850), some 250 forges existed in and around the village, some employing workers and others being simply 'one man bands'. Local farmers set up nail making forges in sheds to supplement their meagre incomes.

Nail making was tedious and hard, and wages were poor, a journeyman nailmaker receiving 7d halfpenny per 1000 nails. The steel rods were forge heated, shaped with a hammer and placed on a fixed cutter, where sharp blows severed them into nails. Nailmaking by hand quickly declined of course with the development of nailmaking machinery, which made the forges obsolete. Not much distress was caused in Silsden by this however, as the decline in nailmaking happily co-incided with the arrival of an expanding textile industry, which offered more attractive employment in the new spinning mills and weaving sheds.

Only one nailmaker, William Driver, continued working effectively after the decline. He had brought in the new machines, and as a result of this was able to stay in business until 1930. At one point he had 40 employees, but with the closing down of his business Silsden's 'traditional industry' came to an end (although Silsden continued to make clog irons as late as 1950).

Silsden is a thriving town. In the heart of its bustle the beck tumbles over the little weir and children play on its banks. Having secured your refreshment you will now be heading back to the canal, and certainly not pausing to explore St. James' Church, which was originally constructed in 1712 out of a barn purchased for ten shillings from the Earl of Thanet. Neither are you likely to seek out Silsden 'Old Hall' which was built in 1682 on the site of an old Civil War arms depot. These and other curiosities await your exploration, but shortage of time will almost certainly deter any such efforts. Unfortunately we have deadlines to meet, so why not come back here another day? One thing for certain, Silsden isn't going to go away!

So once more on the towpath we continue on our way, braving the wrath of the occasional swan, until arrival at Brunthwaite Bridge. Crossing it, we leave the canal and follow the tarmac road up towards the golf club. A right turn, and the road eventually ascends the hillside towards trees, an excellent view of Airedale opening up behind us, with the two monuments on Earl Crag particularly prominent. (See the 'Watersheds Walk/Ivory Towers').

At the first bend, by a seat, the route takes to open country and continues up the right hand side of the gill, soon becoming a charming woodland path through deep bracken. After passing a little dell into which burst a charming cascade the route descends to a waterfall, above which the stream is crossed by a footbridge and a cobbled ford. (Large pipe adjacent). From here on an indistinct path ascends to Gill Grange, which, like many properties in the area, once belonged to the Canons of Bolton Priory.

Beyond Gill Grange and a succession of tracks, the route winds round to Doubler Stones Farm and open moorland is reached at last. The strange, wind-worn rocks of the Doubler Stones are quite unmistakeable, and a left turn from the track, just before it winds round towards Black Pots, leads to them without complication, following the line of a low outcrop of rocks.

This is a good place for a refreshment stop. In wild conditions you can find shelter in the rocks. Here at Doubler Stones we are at the heart of a truly ancient landscape as the wild expanse of Rombald's Moor stretches away towards Rivock Edge. The moor is changing. Heather has given away to crowberry and crowberry to bracken. Like all such changes in the natural environment it is man made, being the end product of numerous successive moor fires. Another new feature in the landscape is the extensive afforestation which has been carried out around Rivock Edge. It was a source of surprise to me, having not travelled this way in many years, and my feelings about it were mixed to say the least. The loss of the heather has been a matter of some concern for many years, yet burying the landscape under a mass of closely packed conifers hardly seems to be a solution! Pine forests are both exclusive and intimidating, being a better deterrent to ramblers than razor wire and landmines! Once more it seems that when it comes to a choice between conservation and profitability, money (as usual) comes first.

According to legend, Rombald's Moor is named after a mighty giant who lived here long ago, and who has since gone downhill to nearby Keighley, where he now throws boulders at hapless passers by in the shopping mall! A more likely explanation suggests that the name is derived from the mighty Norman De Romille Family, who, as we have already seen, once owned virtually all the land in the area. What the name of the moor was in ancient times is anybody's guess, but one thing is certain:- it was frequented by peoples who lived long, long before the Norman Conquest. Indeed, when the Roman engineers built their road over the moors to the fort at Olicana (Ilkley), they would have seen landmarks which were old when the Roman Empire was young, for Rombald's Moor, being sited as it is, so close to the all-important Aire Gap, has long been a centre of prehistoric communication, trade and settlement. It is in fact, liberally sprinkled with minor antiquities:- cairns, enclosures and hut sites. There are also a number of stone circles, the most well known of these being the 'Twelve Apostles', which is still frequented by modern witch covens. The moors, with their contorted boulders, chalybeate springs, burial cairns and lonely, windswept ways were undoubtedly sacred in the minds of ancient peoples, who, being much more finely attuned to the rhythms of nature than modern man, were steeped in 'earth magic' and the worship of 'elemental gods'. This stark attunement is perhaps distantly echoed by the well known local song 'On Ilkla Moor Baht 'At', which, although comic, contains a universal religious idea :- the regenerative power of the earth - the fertility of the land.

The DOUBLER STONES consist of two 'mushroom' shaped rocks with layers of hard grit perched on pillars of softer, eroded sandstone.. Their name is derived from the old celtic 'dwbler' meaning 'dish'. No prehistoric man could visit such a dramatic site as this and be so unmoved as to shrug it off as mere 'wind erosion'. These enigmatic stones, gaunt, grotesque gargoyles of rock hugging this windswept moorland outcrop stand sphinx-like, stone tablets with pages lying open before dark scudding clouds - that cannot read!

Yet perhaps WE can read some of these pages. Small, shadowy people of long ago certainly did, and, in places significant to them but not so obvious to us, they left their 'cup-and-ring' carvings, strange, mystical interfaces between earthly realities and the realms of the spirit world. The carvings here at Doubler Stones consist of two large incised cups on Doubler Stone East, and several cups, lines and deep basins on Doubler Stone West. None of the carvings are immediately obvious or apparent and must be searched for.

These carvings are by no means unique, and better examples exist elsewhere. Study a few detailed maps and you will see that they abound all over the area. The uplands between Aire and Washburn contain, in fact, the highest concentration of these carvings in the British Isles. Probe deeper, and they are found to be divided into four main groups or 'fields', the largest of these being Rombald's Moor itself, particularly along its northern edges. To the south, there is another group on Baildon Moor, and to the east a smaller group of carvings on Otley Chevin. Finally, an isolated (and significant) group is to be found on the moors above Washburndale, particularly in the vicinity of Snowden Moor. This 'field' is crossed by the BEACONS WAY and will be touched upon in SECTION 4.

Of course the most tantalising question of all is 'who carved these mysterious reliefs and why?' What on earth can they signify, these strange circles and depressions incised into remote boulders so long ago? Here is, of course, one of the great mysteries of prehistoric archaeology. Many, many, theories have been forwarded and many more will be. None of them are ever likely to provide a definitive answer.

Let us look at what we do know. It is generally agreed that the date of the carvings may be placed around what is loosely termed 'the Bronze Age' - although some examples have been dated as 'Iron Age'. It is also agreed that there seems to be a tenuous 'line of descent' from the strange spirals, zigzags and lozenges which are frequently found on the walls of Megalithic Passage Graves. Coming forward in time, the designs seem to be further echoed in the curious 'Troy Maze' designs - (a good example of which may found at Alkborough in South Humberside.) Normally the design is associated with turf mazes, but there are carved examples, like those in the Rocky Valley near Tintagel, Cornwall, which are identical in design to mazes depicted on Minoan coins from Knossos in Crete. Some people have commented that the cups and rings seem like staring eyes, and there may be some truth in this, as prehistoric 'Mother Goddess' representations have eyes which follow very similar artistic conventions. Perhaps most surprising of all is a similarity to certain aspects of Australian Aboriginal rock shelter art, some examples of which are known to have been executed in the last century!

From all this it is clear that the ideas behind the designs seem to transcend the boundaries of archaeological epoch, and, in a strange, mysterious way, seep through into modern consciousness. They come in different forms, and from different periods, yet always seem to incorporate the same, traditional shapes in the finished product. Indeed, have we not seen them already, on the ancient crosses which once proclaimed a new religion on Whalley's green sward? Can they not be seen in the vigorous and serpent-like designs so typical of the art of the Viking Age, an age when the followers of Christ were forced by circumstance to share an uneasy cohabitation with bleak, desolate gods which still beckoned men to the high places, to rocks, wells and standing stones? The Church might have held the promise of ultimate salvation, baptising people with water, yet high on the hills people might still hear the voices of the air and feel the cracks and tremors of the living earth! By a shepherd's fire, with smoke spiralling from flickering flames, men might still invoke serpents and hear the roar of the dragon.

In later times, when these gods were little more than a dark memory, holed stones were carried as a defence against witchcraft. 'Eyes of God' were carved on churches for much the same reasons. In the 'like begets like' tradition of ritual magic, the power of 'the stones' had at last been overcome...... by the power of stones!!

Prehistoric standing stones, though man-made, are definitely about art imitating nature. The stones were intended to blend into a landscape in a way that harmonized them with it, making them a part of it. Such megaliths tend to be in short supply in the High Pennines, the implication being that the population was too sparse, or that later developments obliterated what few there were, sometimes converting them into boundary stones or wayside crosses.

Be that as it may, it would seem that the main reason for the paucity of Pennine 'standing stones' is a geological one. If megaliths are about art imitating nature, why go to the troble of constructing them, if nature can provide such sites 'ready made'? The moors, with their twisted rock outcrops, belaboured by the elements, are natural 'megaliths' and perhaps this might go some way towards explaining the profusion of ancient carvings, for surely a natural boulder that was held 'sacred' would have to be identified in some way, to in effect tell passers by that 'this stone has power', or is 'holy'. Whether or not this was the raison d'etre for cup-and- ring carvings is not for me to say, but the use of similar patterns in the christian crosses of later times, suggests there may be at least a grain of truth to this theory.

Of course there are many other theories!! Some people have suggested that the carvings are 'maps' of local village settlements. Aerial photography should, of course, verify such a theory. In practice it does not. On the other hand, there are people quite convinced that the carvings represent the spaceships of ancient extraterrestrials who landed here in prehistoric times! Between these extremes we are presented with a wide range of potential religious symbols and pseudo-scientific theories. Sun signs, moon signs, astronomical charts, stylised human faces have all been associated with the carvings. That the rock art has a symbolic nature seems fairly certain. Two of the designs, the Swastika Stone on Addingham High Moor and the Tree of Life Stone on Snowden Carr can both be positively identified with known ancient symbolism.

The Swastika Stone (which may be visited if you don't mind a two mile detour towards Ilkley) is especially of interest. Later in date than most of the other carvings, it is an unmistakeable 'fylfot' or 'sun wheel', the same symbol we encountered over the monks washing facilities in Whalley Abbey. This symbol was imported from the Middle East during the Iron Age, and is still commonly found today in the religious symbolism of the Indian Subcontinent. That is interesting enough, but of even greater significance is the style of the carving, as it is made up of incised cups and rings, which makes the symbol quite obviously the end product of an artistic evolution which has its origins in the older carvings. The Swastika Stone, like the later Celtic crosses, represents a new religious symbol executed in a 'traditional style'. It therefore seems logical that the older carvings too, are likely to be 'symbolic' in nature, being in turn descended from the older geometries of the Neolithic. The symbols change, but the style remains constant.

It is easy (too easy!) to dismiss cup-and-ring carvings as the awed scratchings of a bunch of primitive cavemen, yet such a hypothesis will not hold water! Truly primitive peoples, the nomadic hunter/gatherers of the Old Stone Age, have left us beautiful examples of representational cave art, which depicts their world with an amazing vitality. Surely it is rather naïve to assume that the well housed and well equipped hill farmers who lived much, much later in Bronze Age Yorkshire should be their cultural inferiors, incapable of sophisticated creative expression? The carvers of the cups lived in stable village communities which would certainly have had a hierarchical structure, no doubt including a 'shaman/witch/priestess' class. These people would have been the custodians of knowledge, both mundane and occult, and their rock art, far from being 'awed scratchings' represent a great step forward from the painted caves of Lascaux; a step from the depiction of the concrete world to the expression of the abstract. If the paintings of Lascaux and Altamira are comparable to 'old masters' then the cup-and-ring art represents its evolution into cubism, for the carvers of the rocks weren't interested in the 'real world' they looked to unseen (maybe even drugged!) realms, seeking to encapsulate symbolic meaning in abstract shapes. (Perhaps they saw the Doubler Stones as 'magic mushrooms!)

As I have already mentioned. There is a universality in the designs, which range from Australia to Arizona. The spiral, the lozenge, the cup and the eye-like concentric rings all seem to have a hidden meaning which stirs up the sediments of the unconscious mind and says:- why do you hesitate? You KNOW what I am! There is a sensation of depth in some of the carvings, the feeling of looking into a 'hypnotic vortex'. There is also a suggestion of fertility, the designs being evocative of leaves, droplets of water, the sun, the crescent moon, and sperms fertilising eggs. The images seem so familiar, yet are so stylised the defy accurate definition. Dowsers have associated the 'spiral force' with the mysterious 'earth currents' we mentioned earlier, and it is possible there was an element of geomancy associated with the carvings, that 'earth harmonising' which the Chinese refer to as Feng Shui.

The true purpose of the carvings will never, of course, be known. It could be that the designs represent a kind of 'proto-writing' a symbolic simplification of religious ideas, perhaps even allied to mathematical expression. The work of Professor Thom with prehistoric stone circles has already revealed the surprising mathematical aptitude of these vanished peoples. It seems fairly certain that they had a considerable store of astronomical knowledge and had not only discovered Pythagoras' Theorem in advance of Pythagoras, but had also discovered the value of Pi - an amazing acheivement!

The symbolic origins of writing are well known. Sea roving Vikings in the Dark Ages, camping out in ancient tombs would carve their runic inscriptions alongside the whirling spirals of their long vanished builders. Viking runes were real letters, a proto alphabet spelling out identifiable messages which may still be read today, (usually ' Kilwulf was here!') But yet each rune had its own, sacred, hidden meaning, the characters being both phonetic letters and abstract religious symbols at the same time. Were they perhaps, the end product of what began with the cups and rings? (Scandinavia too, has its cup-and-ring carvings).

In the light of these magical roots of our everyday writing, could it be that underlying the cups and rings is a deeper yet far simpler meaning? When we doodle - scribble absent mindedly, we let our unconscious minds do the work, aimlessly stringing shapes and patterns together without any obvious meaning. There are persons who claim that they can analyse a persons character from their doodles! I would love to see what they might make of the 'doodles' on Rombald's Moor! I say this, for if you examine most peoples automatic drawings you will discover concentric rings, spirals, lozenges and zig zags, all the contents in fact, of the Bronze Age sculptor's 'pattern book'! These designs have a basic universality, and seem to exist in the minds of humans irrespective of culture, country or level of civilisation. Perhaps the reason that we find the cups and the rings so strangely compelling is because we are a part of them and they part of us, the perfect unity between man and the natural world in which he lives.

Somehow, the carvings seem to be connected with the way we perceive the physical universe. We can 'see' these designs everywhere, in pool ripples, radio waves, microscopic organisms, minerals, atomic structures, stars and wheeling galactic spirals. The list is endless! Perhaps, in a way that is both intuitive and mathematical, the ancient stone carvers were able to symbolize the universality of form and mans physical and spiritual harmony with it. A genetic yardstick of the way we perceive things. As the carvings are a part of the stones, so are they a part of us. Their potency is simple yet quite profound. In harmony with the elements, the sun, the moon, the wind and the rain, these ancient people, wittingly or otherwise, managed to express something that had never been expressed before - the 'machine code' that defines the parameters of human perception!

Enough of theories! Let's pack the flasks and return to the business of walking THE BEACONS WAY. Ascending the moor by shooting butts we reach a stile in a wall, and not far beyond it, emerge onto Addingham Moor Edge, where a sudden and captivating view of Wharfedale opens up. Below us lies Addingham, at the end of Section Three, and opposite, across the valley, the massive bulk of Beamsley Beacon towers over Bolton Bridge, dominating the landscape. Now at last, you begin to feel that the end of our journey is finally in sight.

Addingham Moor Edge is home to a number of rock carvings, the most sophisticated of these being the Piper Stone and the Addingham Crag Stone (see illustrations). These stones are off-route and must be sought out. A right turn along the 'edge' leads to Heber's Ghyll and Ilkley via the Swastika Stone.

The main route however bears left, and brings you very quickly to Windgate Nick, a time honoured 'pass' through the edge which has been a landmark for many centuries, and could in fact, be man made, being possibly part of a prehistoric tackway. Whatever the case, its use as an old drover's road is in no doubt. The 'Gate' part of the name is not, as you might think, derived from 'barrier' but rather comes from the Norse 'gata' meaning 'road' or 'way'. It is, in fact, a name commonly associated with old packhorse and drove routes, and in old northern towns with streets. In days gone by, the drovers would drive their animals over the hills to be sold at the traditional fairs and markets of Northern England. Drovers from the famous Malham and Bordley Fairs would first come down to Skipton, and then, to avoid paying tolls on the newly opened turnpikes in the valleys, they would take to this ancient upland route, travelling from Cringles Top to Doubler Stones via Windgate Nick. From the Doubler Stones the old drove road led past Black Pots Farm, which was once an inn known as the 'Gaping Goose'. From here it led over the moor and the beck, eventually joining the Morton Road at Holden Gate. Now the drovers would proceed onwards to Bingley, the following day striking out for Bradford and the famous Wibsey Fair, where there was always a ready market for horses, cattle and geese. (The geese by the way, would have their feet tarred to enable them to undertake their 'long distance waddles' - sort of avian welly boots!)

Retracing our steps along the edge to the small cairn which lies in a hollow at a crossroads of paths, the main route passes through a gap in the rocky bastion and descends a steep boulder field in the direction of Addingham Moorside. As you climb over the stile in the wall, look behind you to the right. Below the crags in the boulder field just beyond the first descending wall, you will see a carved millstone, a lone relic of an industry which once flourished here on the moor edge. The millstone quarries were certainly in use in the second half of the seventeenth century, and it is quite likely that stone was quarried here at a much earlier date. The quarries lay within the boundaries of the Manor of Addingham, which in the 17th century was part of the estates of the influential and powerful Vavasour Family of Haslewood. The hard, granular gritstone of the moor edge was ideal for the manufacture of millstones to grind corn, and there was a universal demand for them, especially in areas where suitable stone was not locally available.

The Addingham quarries were apparently worked by a succession of leaseholders, the first to be mentioned being one John Wainman of Addingham, who worked the quarry from 1683 to 1711. The quarries were leased to him by a group of local landowners, who in turn seem to have acquired their rights from the Lord of the Manor. The rents obtained by these 'freeholders' were devoted to the relief of Addingham's poor. It is quite obvious that considerable amounts of material were hewn from these crags down the centuries and transporting the millstones downhill from the quarries must have presented serious logistical problems! The 'going' downhill to Addingham is quite steep, and the place is deceptively distant, as we are about to discover.