THE BEACONS WAY

SECTION 4.

Addingham to Otley

"All under the leaves and the leaves of life,

I met with virgins seven,

And one of them was Mary mild,

Our Lord's sweet mother in heaven...."

TRADITIONAL EASTER CAROL

.........And so the curtain rises on Addingham , the start of SECTION 4 and the last watering hole before the end of our journey in Otley. 'Long Addingham' at first sight appears to be something of a nineteenth century upstart, its narrow, winding main street being quite hemmed in by an assortment of houses, shops and mills. It is faintly reminiscent of Cornholme near Todmorden, or Denholme near Bradford, along with all those other semi industrial linear villages which have the misfortune to have busy arterial roads running through them. Addingham's main street has long been an exhaust choked rat run, a constricted winding nightmare to motorist and pedestrian alike. Heavy lorries rumble round its thirteen successive bends and pedestrians tend to meditate upon the meaning of life before crossing the street! Lately however the A65 has bypassed the place and the traffic pressure has eased.

Mercifully though, Addinghams' apparent ugliness is merely skin deep. We have already seen the tranquillity of Addingham Moorside and will shortly encounter the charms of its 'Wharfeside' as we cross what must perhaps be the most romanticised river in Northern England. Addingham in fact stands between river and moor, belonging to neither, but a gateway to both. The Dales Way runs along the riverside, and on reaching Bolton Bridge (just upstream) enters the Yorkshire Dales National Park. As if to supplement this, paths fan out from Addingham in all directions.

Addingham does have a history, which began long before the age of mills and industrial upheaval. Within a few minutes of the main street we can enjoy the serenity of St. Peter's Church, which is believed to have been founded in the Dark Ages after one of St. Aidan's missions. The church is built on a mound, and some writers have suggested that this was the site of a 'druid temple', for according to one local source the outline of the ancient circle becomes quite distinct after a light sprinkling of snow. (As if to add to this mystical atmosphere a cutting from the famous Glastonbury Thorn was planted in the churchyard some years ago).

To corroborate Addingham's ancient origins there is also a fragment of an Anglo-Saxon cross, and it is also known that there was a settlement here around 876, when the Danes, who attacked York by sailing up the Ouse, forced the (then) Archbishop to flee and seek refuge here. This raises an interesting question:- why Addingham?? We can only speculate of course, but one possible explanation might be found in the location of Anglian 'national' boundaries. Prior to the incursions of the Viking Age Northern England was inhabited by two different ethnic groups:- Mercians and Northumbrians. Although both nominally 'english' the two groups were culturally different, and their royal houses, descended from Penda and Edwin respectively, had long been mortal enemies. The Mercians ruled over what is now the Midlands, but Mercian rule extended into Pennine West Yorkshire. A religious difference also existed at one point, for although the whole of Northern England was Christianized prior to the Viking Age, the earlier part of the Anglian period had seen the Northumbrians embracing the new faith while the Mercians remained staunchly pagan. With the fall of Edwin, the star of pagan Mercia rose high, and, uneasily allied with the Celts, they swept into Northumbria, even sacking York itself. This triumph was not complete, however, and it was not long before the Northumbrians reasserted themselves, and the two kingdoms existed uneasily side by side, right down to the arrival of the Danes.

The evidences of these two kingdoms (chronicles apart) are drawn from the distribution of place names, which infers that the original line of separation between the two kingdoms ran down the Aire Valley. South of the Aire, for example, the Northumbrian 'borough' as in 'Knaresborough' becomes the Midland Mercian 'bury' (for example Dewsbury or Stanbury). The place name element 'Worth', so common around Keighley, is Mercian in origin, and is not found in Northumbrian Wharfedale. Here then, was a 'national' boundary, an ethnic border beyond which the people would have felt loyalty more to the Kings of Mercia than to their Northumbrian enemies in York (Eoforwic). Times change, but even in times of peace bitter memories die hard. Perhaps this is why the Northumbrian Archbishop, seeking refuge from the Danes, chose to flee no further than Addingham, perhaps imagining that he might receive a cooler welcome 'over the hill', where men spoke with a Mercian dialect.

The last Viking terror to sweep across the North was instigated by William I., the 'Nor(th)man', for after the Conquest, and the fierce resistance to it by the peoples of the North, Addingham, along with the rest of the district was 'laid waste'. In the Domesday Book it is described as 'Terra Regis' ie- 'belonging to the king', who had taken posession of it along with the rest of Earl Edwins pre-conquest lands. In the general carve-up which ensued the Manor and Advowson of Addingham was eventually granted to Mauger De Vavasour by Robert De Romille towards the end of the reign of Henry III. It was to remain in the possession of the Vavasours from 1279 to 1714.

Like most communities in the area Addingham undoubtedly suffered on occasion from the depredations of the Scots who swept repeatedly down the Dales throughout the Middle Ages. Each summer they would come looting and burning, often forcing the Prior of Bolton and his Canons to seek refuge in Skipton Castle. After Bruce's triumph at Bannockburn there was no holding them, but when they eventually met their 'Waterloo' at Flodden Field in 1513, the Scots came no more, and the revenge of the Dalesmen was complete. Addingham, like many other villages in Craven sent its contingent of soldiers with Henry Clifford, The 'Shepherd Lord', to meet the Scots.

"From Penigent to Pendle Hill,

From Linton to long Addinghame,

And all that Craven Coasts could till

They with the lusty Clifford came......."

And years later, when the Scots were but a distant memory, there came a new invasion:-of mills and machines. The Industrial Revolution had arrived in Addingham.

The creation and development of the textile industry in Addingham was largely due to the Cunliffes, forebears of that famous Lister family who built the great Manningham Mills complex in Bradford, and played such an important role in the industrial and political development of that city. (Samuel Cunliffe Lister, the Ist Baron Masham, who knew Addingham well, is buried in his family's vault here). The Listers had at least three mills in Addingham, and had the village been easier of access it is quite probable that they would have built a massive industrial township here, which would surely have done little to enhance the charms of this part of Wharfedale! The earliest textile industries in Addingham were, of course, cottage based, and many of the houses crowding Addingham's main street were built with an extra storey to accommodate the handlooms, sometimes being dubbed 'Addingham's Skyscrapers'! This prosperous period of domestic weaving came to an abrupt end, however, with the advent of the machines, which brought unemployment, hardship and poverty to large numbers of workers, who found their traditional skills rendered obsolete virtually overnight! The change was not to be welcomed in Addingham.

In 1826, when the Listers sought to install the new power looms in Low Mill, close to the Wharfe, the spirit of Luddism reared its head and they were hotly opposed. The mill was attacked and the rioters had to be dispersed by the military. One of the rioters, who fell into a cesspool whilst trying to climb into the mill was fatally smothered. In the end of course, progress was unstoppable and the mills reigned supreme; but this supremacy too was fated to come to an abrupt end with the recession of the industry in the early 1960's, when the mills closed down, along with Addingham's now completely vanished railway link.

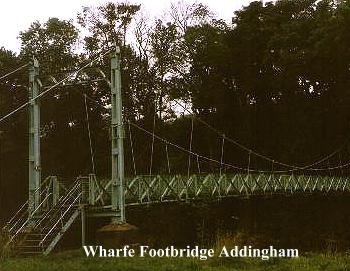

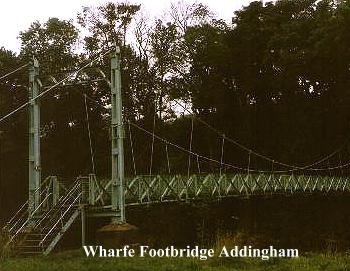

Leaving Addingham, we head for the little suspension bridge that crosses the Wharfe on the far side of the village, near the Dales Way. The existence of this little bridge was of vital importance in the planning stages of the Beacons Way, for at that time I was unsure as to whether or not there was a crossing of the Wharfe at Addingham. I had, in fact, to make a preliminary visit here, before starting on the Beacons Way, just to make sure that the bridge was there! I was greatly relieved to discover this secluded crossing, with its pleasant, tree-shaded path heading off in the direction of Beamsley Beacon. It gave the 'green light' to the whole idea.

The Wharfe is a famous and a beautiful river. Here at Addingham it looks so peaceful, its clear, trout filled waters sliding gently over its boulder strewn bed. Midges and flies hover over the water and anglers sit on the velvet green turf and shingle banks, lost in a world of their own. Compared to the brooding, sullen waters of the Aire, it seems a world apart, but yet it is perhaps wise to remember the old saying:-

"Wharfe is clear and in the Aire lithe,

Where the Aire drowns one, the Wharfe drowns five."

The Wharfe is, in fact, a notoriously treacherous river. The story of the Boy of Egremond who was pulled back by his hesitant hound while trying to jump the seething waters of the Strid needs no further elaboration here, save to say that this notorious bottleneck of the Wharfe is but a few miles upstream from this gentle spot. It is a river of changing moods. Fierce rapids and gentle pools often lie in dangerously close proximity, and the onset of a sudden rainstorm can quickly swell this innocent looking stream into a torrent of alarming proportions. Potholers visiting the upper reaches of the Dale watch the Wharfe carefully, for its level, combined with the local weather forecast is often used as a yardstick by which to measure their chances of subterranean survival! Being fed by so many underground streams, the Wharfes moods can change very quickly, as I once discovered when I picked the wrong night to camp by the river near Kettlewell Bridge! Yet the Wharfe is still beautiful. Even if it is a wolf in sheeps clothing, that wolf certainly knows how to dress!!

From the Wharfes' meadows our route meanders up the hillside toward Beamsley Beacon. Between leaving West Hall Lane and rejoining the metalled road at Beech House, we follow a most attractive bridle path which in summer is not only a dense jungle, but also a paradise for the amateur botanist. When I came gasping and sweating up this path on a hot summer's day I could not help but notice the simply phenomenal array of wild herbs, shrubs and flowers. Here is a list containing some of them:-

GREATER BELL FLOWER (Campanula latifoliae) Flowers July.

BETONY (Betonica officinalis) Flowers June- September

GOOSEGRASS or CLEAVERS (Galium apirine)

MEADOWSWEET or DROPWORT (Filipendula ulmaria) Smells like marzipan. Contains vanilla!

NIPPLEWORT (Lapsana comminis) flowers-July to September.

PINEAPPLE WEED (Matricaria matricarioides) Bitter, rank smell.

RATS TAIL PLANTAIN (Plantago major)

HERB ROBERT (Geranium robertianum)

TUFTED VETCH (Viccia cracca) distant relative of the garden pea!

FOXGLOVE (Digitalis purpurea) Poisonous. Used to treat heart disease.

RED CAMPION (Silene dioica)

NETTLE (Urtica dioica) stings!

ROSEBAY WILLOW HERB (Epilobium augustifolium) Purple pest!

HOLLY (Ilex aquilifolium) Female (as you should know!) has red berries.

HAWTHORN (Crataegus monogyna)

WILD OAT (Avena fatua)

Passing this way armed with a reference book, you would no doubt discover even more plants than I did. The meadowsweet, I recall, was particularly delightful, and even now as I write, months later, I can still smell the sweet marzipan aroma rising from a specimen pressed in the leaves of my notebook! Once smelt, the plant is never hard to identify thereafter.

Now at last, we come to our third and last beacon:- Beamsley Beacon or, as it is sometimes known, Howber Hill. The summit of the Beacon is 1300 feet high and is capped with Kinderscout Grit. It commands the surrounding countryside and offers some good views, particularly in the direction of Bolton Abbey, where the ruins of the Augustinian Priory (it was never an 'abbey') can be seen in the distance.

Like Pinhaw Beacon, Beamsley Beacon does not lie too far from the metalled road which runs past it down towards Bolton Bridge; and, (also like Pinhaw) it once had a guard hut on the Beacon which was built and manned in Napoleonic times to warn of French invasion. There the resemblance ends, however, for Beamsley Beacon has credentials rather more impressive than those of its humble neighbour. Capped by a rocky cairn and a concrete triangulation pillar, it is an impressive rampart of boulders and scree. It is, in fact, the best eminence we have encountered since leaving the summit of Pendle, and the burnt stones on the summit cairn testify to its recent use as a beacon site, probably asw part of the 1988 Armada celebrations.

Beamsley Beacon is a very ancient landmark. Its alternative name of Howber Hill testifies to its antiquity, being derived from the anglian 'how' (burial mound) and 'ber(g)' meaning 'hill' or 'fort'. Other explanations have also been hazarded:- it could, for example, be derived from the Anglo-Saxon 'heawan' meaning 'to view', although I personally favour the first explanation.

Whether or nor Beamsley Beacon was ever actually used as a fortress is uncertain, but there is little doubt that it was used as a prehistoric cairn burial site, for no Beaker community would leave such a fine viewpoint as this 'untenanted'.

When Howber Hill was first used as a beacon site is also unclear. I have not discovered any evidence of it being used to warn of the Armada, but the Bolton Abbey Registers of 1803 record that it was put in a 'state of repair' to warn of French invasion, which implies that the hill had been used as a beacon before this time. Four guards were employed to man it in 1803, and according to an old chart of that date it received its light from Pinhaw Beacon, which it duly relayed on to Otley Chevin. This was the last time that the beacon system was in serious use. No such national emergency was to loom again until the dark days of 1940, by which time the beacons had been long obsolete.

The Beacons were not always used for warnings however. We have already mentioned the great Victorian Jubilee celebrations which were held on Pendle Beacon, and it should come as no surprise to discover that Beamsley Beacon was also lit on the same night in June, 1897, when over a score of fires could be seen on the surrounding hills. No doubt a good time was had by all parties concerned.

From Beamsley Beacon our route runs to the north east, towards Round Hill, following a line of ancient boundary stones (marked 'LN'). Although there is no official right-of-way along this ridge, the path is, nevertheless, quite well defined and well frequented, and you are unlikely to be challenged by anyone. The boundary marks the division between the ancient parishes of Skipton and Ilkley, but could also mark a much earlier, possibly Celtic line of demarcation.

Soon, after crossing a marshy 'flat', the route ascends to the wall on the summit of Round Hill, where we bear to the right, now at last turning towards Otley. On Round Hill a rash of stones marks the probable site of yet another Bronze Age burial cairn, and beyond the wall, if the weather is clear, there are views right across the Vale of York to the White Horse of Kilburn in the Hambleton Hills.

Nearer at hand, the giant 'golfballs' of the NATO satellite communications centre on Menwith Hill dominate the scene. How lucky are the inhabitants of Washburndale! Not only do they have such a lovely landscape to live in, they can also rest assured that in the event of a nuclear war they will be the first to get atomized, as Menwith Hill is undoubtedly a 'number one target'. Washburndale would be the first casualty of World War III !

I have mixed views about Menwith Hill. I recall the story of the peace protester from Hebden Bridge who was arrested and imprisoned for trespass and criminal damage. Her crime? Pushing a daffodil through the perimeter fence! Yet I, along with hundreds of other walkers tackling the Lyke Wake Walk, have strolled past the perimeter fence of the Fylingdales Early Warning Station in the dead of night, without being challenged by anyone! It would seem that because nocturnal hikers are not voicing their politics, there is no need to make 'an example' of any of them. Wear a black coffin on your sleeve and you may pass unmolested, but if you're wearing a CND badge, then you'd better watch out!

Casting politics aside, it must be admitted that these 'golfballs' do exhert a strange influence over the landscape. Like them or loathe them, no one can argue that they are not man-made 'landmarks' of the finest order, on a par with Emley Moor Transmitter, or the Jodrell Bank radio telescope. If you didn't know better, you might think that aliens had arrived here from another galaxy, leaving their giant pods on the moors, dominating the landscape like the eggs of some gigantic spider! The whole thing looks like something out of the 'Quatermass Experiment', arousing feelings of awe and horror! No doubt the chieftains of old who slumber in those ancient cairns would be terrified could they see the awesome apparition of Menwith Hill, just as we are terrified (but for different reasons). To say that the 'golf balls' fit in with the landscape would be the lie of the century, but despite my feelings I must admit that they are strangely compelling. It is not impossible to imagine the industrial archaeologists, or 'technological antiquarians' of the next century speaking of these monstrosities in the same endearing terms which today's enthusiasts apply to derelict Cornish engine houses, disused railway viaducts and boarded up textile mills. It simply depends upon how you look at it. Beauty (or ugliness for that matter) is in the eye of the beholder! It wasn't too long ago that a certain person (who shall remain nameless!) was waxing lyrical about the sylvan charms of the Cononley Lead Mine! My generation would love to see the golfballs torn down, but who knows? Perhaps the next generation (if there is one) will fight with equal determination to see them preserved:- as an example of our technology and a monument to our folly! For if the human race does have a future, these sort of places don't!

Following the wall and boundary stones downhill towards Stainforth Gill Head, the path soon encounters some boggy ground, and crosses the line of the old Roman road from Ilkley to Aldborough (Isurium), although you wouldn't notice it without a map. (In fact you wouldn't notice it WITH a map!) Where the actual road crosses our path there is no visible trace of it, but further along the route, looking back from Lippersley Pike, its faint line can, if conditions are right, be seen descending the slopes of Blubberhouses Moor.

At Gawk Hill Ridge we encounter another old route:- this time the old packhorse way which led from Ilkley to Ripon via Gawk Hall Gate. The summit of the pass is marked by an old milestone with pointing hands which informs us that it is twelve miles to Ripon and three to Ilkley. It seems strange to think that this lonely path, passing over this wild and inhospitable watershed, was once a busy artery of communication alive with the shouts of packmen and their trains of jagger ponies. Like the railway line in Addingham, this busy 'main road' has now gone forever, to be left alone with its memories, and its ghosts!

After a potentially 'wet shod' crossing of Stainforth Gill, we ascend through the heather once more to the summit of Lippersley Pike, where a shooting butt stands atop the burial cairn of yet another Beaker chieftain. At 1,083 feet, Lippersley Pike is the highest point on Denton Moor, and is, although you wouldn't think so to look around you, surrounded by numerous sites of interest to the archaeologist. Many flints have been found here down the years, and it is believed that the moor was once occupied by the 'Broad Blade' people of the Neolithic period. Other burial cairns and a 'cup marked' rock are near at hand if you have time to seek them out.

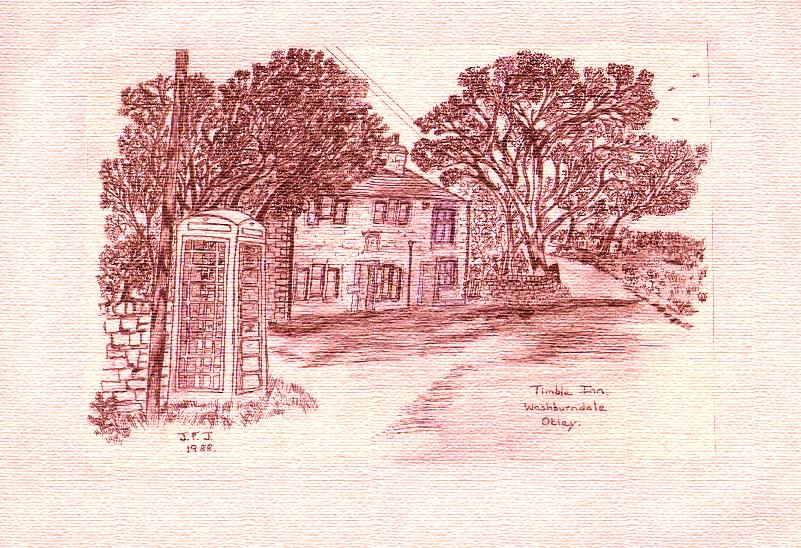

More likely than not though, you will not have 'the time'! It will no doubt be well into the day by now, and we still have some considerable distance to go before we reach the end of our journey. Beyond Lippersley Pike a ladder stile takes us over into a landscape of baby christmas trees, and a little further on, by the ruins of Timble Ings, a rather more mature coniferous forest suddenly blots out the surrounding landscape, and we are forced to play 'babes in the wood', following a track through tall, densely packed firs which shut out the light and turn the woodland floor into an arid, needle strewn waste as a result. Soon we leave the forest, and after crossing the Blubberhouses Road at Lane End, we simply take to the tarmac and follow the road down to the village of Timble, where refreshment may be secured at the Timble Inn. (Enjoy it if you can:- you will need it!)

The Timble Inn is quite old, and was for a long time held by the Lister Family, whose ancestors have lived hereabouts for close on six hundred years. The Village Institute opposite was built in the last century by a local man who had made his fortune in the Americas and wished to be remembered as a public benefactor.

The way out of Timble is confusing. From the top of the village, having doubled back behind the Inn, an indistinct path leads down the pastures to a little footbridge which crosses Timble Gill near a junction of streams. Here, in this secluded glen, where the tiny beck babbles over mossy boulders beneath a canopy of trees, we are once again about to make a 'discoverie of witches', for here, in the early seventeenth century a group of local women are reputed to have partaken of a witches feast!

The remarkable story of the Timble Witches begins in the years leading up to 1621, which marked the publication of a most amazing book entitled 'DAEMONOLOGIA- A Discourse on Witchcraft, as it was acted out in Family of Mr. Edward Fairfax, at Fuystone, in the County of York in the year 1621'. Its author, Edward Fairfax, was the 3rd son of Sir Thomas Fairfax, who had been knighted in 1576 by Queen Elizabeth. (He died in 1599).

The Fairfaxes were a distinguished family. Edwards two elder brothers, Thomas and Charles, were both soldiers. Charles fought in Flanders at the Battle of Neuport and the Siege of Ostend, finally being killed in action in 1604. The eldest brother, Thomas, inherited his father's Denton estates, and also distinguished himself in the continental wars, being knighted by the Earl of Essex before Rouen. Thomas also followed a diplomatic career, being sent to Scotland to negotiate with King James, there being offered a title (which he refused). Thomas' son, Ferdinando, and his grandson Sir Thomas (Black Tom) Fairfax, were both destined for fame and glory in the English Civil Wars, 'Black Tom' distinguishing himself in the early Yorkshire campaigns of the war, eventually becoming Commander-in-Chief of Parliament's 'New Model Army'. He was later to be instrumental in bringing about the Restoration of Charles II.

Edward Fairfax also had two sisters, Ursula and Christiana, married respectively to Sir Henry Bellasis and John Aske of Aughton, (whose unfortunate ancestor was cruelly executed for leading the ill-fated 'Pilgrimage of Grace'.) A fine carved figure of Ursula Fairfax may be seen in the north aisle of York Minster, where she kneels in prayer alongside her husband upon an exquisitely carved memorial. It is ironic that the Bellasis's and the Fairfaxes were fated to take opposing sides during the Civil Wars.

These, then, were the powerful and influential relatives of Edward Fairfax, whom we might imagine to have been cast in very much the same sort of mould. Yet this was not the case. Edward Fairfax was a shy, retiring sort of man, "preferring the shady groves of Knaresborough Forest before all the diversions of camp or court." He preferred to seek renown through the medium of the pen rather than that of the sword, and along with Spenser, he was one of the founders of the modern school of English Poetry. Edward Fairfax was a scholar, and was the translator of Tasso's famous poem, 'Jerusalem Delivered', which he completed and published in 1600.

Apart from this however, very little is known about him. It seems likely that he was born at Denton, and perhaps educated in Leeds; but no information exists to back up either assumption. Wherever Fairfax received his education, it must have been a good one to produce such an excellent scholar, and undoubtedly the young Edward must have been of a studious 'bent.' It is generally believed that he came to live at Newhall in Washburndale, (a house long submerged beneath Swinsty Reservoir) some time around 1600. It seems that he was newly married, having taken as his wife a Miss Laycock of Copmanthorpe near York, and according to the parish records his daughter Elizabeth was baptised at Fewston in 1606. In 1607 he is reported as living in a house called 'Stocks' near to Leeds Parish Church, but by 1619 he had finally made Newhall his permanent abode, and was to reside there until his death in 1635.

It was during this final period of occupation, within a mere two years of permanently settling at Newhall, that Edward Fairfax began to experience those 'strange disorders' which began to afflict his family, disorders which, in a manner most uncharacteristic of an 'enlightened scholar', he was to blame on the womenfolk of several local families, whom he accused of being witches. He produced 'evidences' of spells and black magic, and related how these 'witches' had bewitched his daughters Helen and Elizabeth and caused the death of his baby daughter Ann. All these events he was to describe in great detail in his 'Daemonologia'.

The 'Daemonologia' is a strange work to say the least. Generally dismissed by modern writers as the superstitious and suspicious aberrations of a mind capable of producing better things, it is, nevertheless, a strangely compelling tale. Fairfax's basic sincertity cannot be doubted, for he quite obviously believed in what he wrote and in the light of that we can only conclude that he was either suffering from self delusion or else something very unusual actually did take place in the Washburn Valley in 1621.

The real truth of course, will never be known; but working on the basis that there is seldom smoke without fire I am inclined to think that perhaps there was some sort of 'local conspiracy' directed against Fairfax, and that perhaps certain 'traditional practices' had a role to play in that conspiracy. Having said that, however, it seems highly unlikely that Fairfax's 'witches' were actually guilty of the offences which he accused them of.

Let us look at the backdrop to the story, and imagine the scenario. We have a wild, remote valley, deep in the fastnesses of Knaresborough Forest, inhabited by closely knit local families who have lived here since time immemorial. Round about 1600 enter Edward Fairfax and his family. He is a gentleman, a scholar, something of a recluse, and a relative outsider. Fairfax does not like or get on with his neighbours, and they do not particularly like him. It is only a matter of time before there is conflict. Fairfax is a highly educated man, with powerful relatives. His neighbours are poor and ignorant. Their only way of dealing with him is to close ranks; but this only makes Fairfax even more distrustful of them. His daughters fall sick, and in the mind of a suspicious man like Fairfax this can mean only one thing:- it is the work of witches!

That Fairfax 'looked down his nose' at his neighbours seems fairly certain. "So little is the truth of the Christian Religion known in these wild places and among these rude people", he wrote, as he accused them of resorting to 'wise men' and 'wizards' to treat their animal's ailments. "These Wizards," he continued, "teach them to burn young calves alive and the like; whereof I know that experiments have been made by the best of my neighbours, and thereby they have found help, as they reported."

Despite Fairfax's obvious disdain, there is probably a grain of truth to this story. The village 'wiseman' or 'cunning man' had long been a feature of rural life, and was still known to be in existence in East Anglia as late as the mid nineteenth century. He was of course the modern descendent of the old 'shaman' or 'witch doctor', and was no doubt the custodian of occult knowledge and lore passed down orally by generations of his forebears. There is no reason to doubt that such pagan ideas were alive and well in early 17th century Yorkshire.

Six women were accused of witchcraft by Edward Fairfax. Most of them were women under whose care and companionship Fairfax's children had spent some time. The first of these women, Margaret Waite, was described as 'a widow' who had come to live in the area some years earlier, bringing with her "an evil report for witchcraft and theft". She was alleged to have taken a pennyworth of corn from Fairfax without paying for it! She was accused, along with her daughter, who had 'impudency and lewd behaviour' added to the list of her mortal sins! The third 'witch' was "Jennet Dibble, a very old widow, reputed a witch for many years; and constant report confirmeth that her mother, two aunts, two sisters, her husband and some of her children have all long been esteemed witches, for that it seemeth hereditary to her family." She was, undoubtedly (in Fairfax's eyes) the ringleader of the conspiracy. Next on the 'list' came Margaret Thorpe, another widow. She was seen to throw pictures of Fairfax's children into water, and to cut the children's names on loaves of bread, looking for 'signs' as she threw them into a pool! The fifth 'witch' was Elizabeth Fletcher (formerly Foster) who supposedly had such a "powerful hand over the wealthiest neighbours about her, that none of them refused to do anything she required." She had been watching when Elizabeth Fairfax fell off a hay mow, and was blamed by Fairfax as a result. Last of all was a woman by the name of Elizabeth Dickenson, who, according to Fairfax, was accused of bewitching the daughter of his neighbour, Maud Jeffray. (Was she perhaps related to that 'Dickonson Wife' who chased after young Robinson, when, some years later he was to relate the sensational story which led to the Second Pendle Witch Trial of 1633?)

The charges levelled against the women by Edward Fairfax ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous. The usual 'imps' and 'familiars' appear in the account:- Jennet Dibble's 'familiar', for example, was a "great black cat called 'Gibbe' which hath attended her now above 40 years" ( an amazingly old moggy if true!) Margaret Thorpe's 'familiar' was a bird, "yellow in colour, about the bigness of a crow - the name of it is 'Tewhit'". (which is of course, the common local name for Vanellus christatus:- the Lapwing.) Fairfax accused the women of using 'images' to bewitch his daughters;- "The women told the wench these were the pictures by which they bewitched folks; the picture of my daughter Helen was appareled like her in the usual attire, with a white hat and locks of hair hanging at her ears, and that of her sister was attired in the child's holiday apparel; the rest were naked. Helen said to the woman, 'these pictures of ours have cherry cheeks, but whose picture is that which looketh so pale?' The woman answered, 'this is Maud Jeffray's'". Whether or not these 'pictures' were actually the wax or clay 'devil dolls' used to work black magic is unclear. Fairfax obviously thought so for he writes:- "The pictures she showed, (which indeed were images); but I alter not the words which the children and the witches used." As a result of such dark practices (at least in Fairfax's mind), his children kept going into trances and fits and behaving in irrational ways, at one point being temporarily struck blind. Most sensational of all was Fairfax's allegation that the witches had abducted his daughters, and had carried the three children to a Midsummer's Eve bonfire on the moor top, so forcing them to take part in a pagan Beltane Feast. When, sometime later, his little daughter Ann died, this was the last straw for Fairfax, and, against the better judgment of the vicar of Fewston, Henry Graves, he had the 'suspects' arrested and bundled off to York Castle to await trial on charges of witchcraft.

Fairfax's rashness reaped its just reward. His 'evidence' though rich enough in 'hearsay', did not, as Graves had warned him, contain enough hard evidence to convict the women. The accused witches were twice brought before the court, and, to the credit of the York Justices and the dismay of Fairfax, were adjudged innocent and immediately acquitted!

On their return home, the Timble women, no doubt elated by this rare triumph of seventeenth century common sense, promptly organized a celebration to toast their good fortune. Along with their families and friends they descended in force upon Timble Gill where a most amazing 'witches feast' was held! According to Fairfax, whose account, it must be admitted, was 'third hand':- "their meat was roasted about midnight. At the upper end of the table sat their master viz., the devil"(and)" at the lower end Dibb's wife, who provided for the feast, and was the cook." This was on Thursday 10th April 1621. According to Fairfax, the feast continued through the night, right through to the dawn of Good Friday.

Having failed in his efforts to get rid of his troublesome neighbours and to relieve the afflictions of his children, Fairfax decided to set down his version of events, which resulted in the publication of his 'Daemonologia', and there, really, is an end to the story.

Of Fairfax's subsequent dealings with his neighbours we know nothing. Humiliated by these 'rude' people, it is surprising that he did not simply sell up and move elsewhere, but move he did not, for he remained at Newhall until his death in 1635.

So what are we to make of this curious and fantastic story? Most modern writers, Sir Walter Scott among them, incline to the view that the whole affair was purely a product of Fairfax's fevered imagination. Other writers of a more mystical bent, like Guy Ragland Phillips, take the story more seriously and suggest that the Timble Witches were actually custodians of a traditional occult lore which was meaningful to the whole local community. Phillips even goes so far as to suggest that Fairfax's children were carried off to the May Eve celebration along an 'earth current'- a 'ley'. For my part, I prefer to steer a middle path. Much of what Fairfax says in his book is sheer nonsense, the fantasies of a distrustful, suspicious and potentially paranoid mind. Yet having said that, there must have been SOMETHING to the story. That Fairfax's children suffered illness, for example, cannot be doubted. The 'trances' and 'enchantments' were perhaps all too real. It seems likely that they may have suffered from epilepsy. This occurs in two forms:- the'grand mal' which is epilepsy's most well known (predominantly adult) manifestation, causes violent fits and frothing at the mouth. The 'petit mal' form, however, is less well known and is usually found among children. Its manifestations are far less dramatic, so it attracts less attention. Its chief symptoms are 'daydreams' and 'trances' which come and go at certain times. This daydreaming is usually accompanied by a vacant expression, and is actually a mild form of epileptic fit. Such a malaise as this, especially if accompanied by occasional attacks of 'grand mal' epilepsy, could quite easily have convinced a man like Fairfax that his children were bewitched! (Helen Fairfax, interestingly enough, is described as being 'slow of speech' finding it 'rather hard to learn things fit'. She was 21 years old at the time.)

As for the accused women, the implications are even odder. The children were frequently under their care, and, for all the evidences of 'witchcraft' which Fairfax pumped out of his girls, there is no indication that the children either distrusted or feared these women at all! On the contrary, it appears that the 'witches' cared for and possibly even liked Fairfax's children. Certainly when they were tried at York their 'good character' prevailed and they were released from custody.

But why the Beltane revels and the 'witches feast'? Did Fairfax make it up, or did these events truly take place? It seems unlikely that he concocted the story , for despite his obvious misinterpretation of the facts, Fairfax is basically sincere. It seems likely that in this remote part of the Forest of Knaresborough the local people were still observing ancient customs and traditions which were probably extinct in more 'civilised' areas. In 1621 we are in the midst of the 'puritan revolution'. By the time of the Commonwealth country sports and mayday revels were to be banned altogether, condemned by sober puritans as 'popish mummeries'. In a sense, Fairfax himself is symbolic of the 'new attitude' towards these old rural ways. To him 'wisemen' and 'may revels' were the work of the Devil. Unlike the local vicar, Fairfax had obviously not learned that 'when in Rome....' You do as the Romans do!

Finally there is a curious postscript to our story. The wife of Fairfax's neighbour, who resided at Swinsty Hall, was "in strange case, and often moved to destroy herself or her child or some of the family." Her husband was, (in Fairfax's words) a "great favourer of these women questioned, especially of Elizabeth Foster,(Fletcher) usually called Bess Foster, who is very familiar in his house, yet he hath little cause to do so, for besides the troubles of this wife, he had a former wife bewitched to death by the witches of Lancashire, as in the book made of those witches and their actions and executions you may read." The name of this neighbour of Fairfax's was Henry Robinson. Robinson was a money lender and was the richest man in the neighbourhood at that time, having acquired Swinsty Hall in 1590 as a result of foreclosing on a mortgage held by one FrancisWood. Robinson came from Old Laund in Pendle Forest, and had not only been actively involved in the1612 witch trials, but was also a relative of that notorious father-and-son duo, the Robinsons of Wheatley Lane, who were fated to play such a crucial role in instigating the second Pendle Witch scare of 1633. It is strange that the name Robinson keeps appearing in the early seventeenth century in connection with witchcraft accusations. It almost seems as if they had some kind of vested interest in the business!

There is another story associated with Timble Gill beside that of the witches. According to local tradition a man by the name of Wardman was murdered in the Gill, struck dead with the butt of a gun. His ghost reputedly haunted the spot thereafter, terrifying travellers who had the misfortune to be in the glen after dark. Such a menace did this 'flay bogle' become that a catholic priest was called in to exorcise it. (No- I don't mean take it for a walk!) Thereafter, it was not seen again, but having said that I still think we ought to push on before it gets dusk! I'm not rushing you...but...what? Me? Of course I'm not afraid of ghosts!!!!

So, leaving witches, ghosts and boggarts behind us, (hopefully!) we continue on our way, following a series of paths and tracks which soon meet tarmac on Snowden Carr Road. Our route turns right, heading up the hill past Crag House, but a quick glance at the map will tell you that it would be far easier to cheat and knock nearly a quarter of a mile off the route by simply proceeding straight along Snowden Carr Road. If the day is late and you are tired, please feel free to do so; but if you do take the short cut, you will miss out on seeing what must surely be one of the high points of the whole walk:- TheTree of Life Stone on Snowden Moor. (Yes, there is method in my madness!)

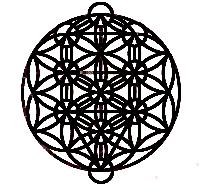

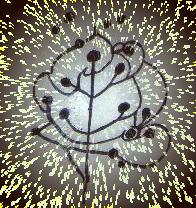

Near the junction of Snowden Carr Road with the Blubberhouses Road at Psalter Gate, ('Salter's Way'- another old packhorse route), a path leads up onto Snowden Moor through heather, passing shooting butts and stone stoops. At the top of the slope, a left turn leads along the crags, passing a succession of rowan trees, and we follow an indistinct path which leads around the moor edge, doubling back high above the road. Soon, beyond a broken fence, near a lightning blasted rowan tree, we come across a boulder carved with an unmistakable pattern of cups and rings. This is the 'Tree of Life' Stone.

Here is where the Timble Witches probably lit their Midsummer's Eve bonfire, for, according to Eric Cowling, the spot has been long known to local people, and has been frequently used by them for 'Mayday religious services'.

The 'Tree of Life' is a mystical and highly complex symbol. Trees figure universally in the language of myth, religion and magic, and, down the centuries, they have taken on a deep occult significance. The oak, as is well known, has long been venerated, being sacred to Zeus, Thor, Yahweh and Celtic Druids alike. The yew tree, so common in churchyards, wasn't grown simply to ensure mediaeval archers a continuing supply of longbows, but was also a symbol of death. The Viking 'World Tree', Yggdrasil, was an ash, and it was upon such a tree that Odin hanged himself for 'nine full nights,'a 'sacrifice to himself alone' in order that he might grasp the wisdom of the runes.

Tree veneration did not end with the arrival of Christianity either. The deep occult significance of Jesus on the cross was not lost on peoples whose ancestors had once worshipped Thor and Woden. The 'Tree of Calvary' is easily recognizable in the art style of the Anglian preaching crosses, which also contain those 'lozenge and spiral' elements which we have associated with megalithic and bronze age carvings. The idea that Jesus was crucified upon a tree rather than on a cross has persisted in northern Europe until comparatively recent times. The old Easter carol, 'The Leaves of Life' bids us:-

"Go down go down into yonder town,

And sit in the gallery,

And there you'll see sweet Jesus Christ

Nailed to a big yew tree............"

The same idea exists in other mediaeval carols, and it is significant (in an age when the liturgy was in Latin), that these songs expressed the simple (and superstitious) faith of the common people, rather than that of the educated classes. (After all, the 'peasants' knew all about the significance of trees!)

The real 'Tree of Life', however, guardian against witches, lightning and the powers of darkness, is none of those I have mentioned. It is the rowan, or mountain ash which claims this singular honour. Its bright, orange/red berries make a lovely sight in the autumn, and also make a pleasant (if slightly bitter) wine. According to folklore, evil cannot abide it, and black magic is overcome by its power. There are not many trees on Snowden Moor. We passed two of them as we walked along the crags - they were both rowans! No doubt the ancestors of these trees have flourished here since time immemorial. Perhaps they already grew here when unknown hands essayed to symbolise their power in cups and rings etched upon enduring stone. What better place.....among the 'Leaves of Life'!

With the passage of the centuries numerous trees must have come and gone, yet this strange carving, the daddy of them all, has endured, and still remains, a vivid and enigmatic vision in the heather.

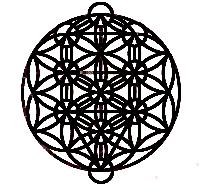

What are we to make of it? What does it mean? Fortunately the question is not as hard to answer as you might think, and that answer also helps to give us some further insight into the meaning of all those other 'cup and ring' carvings which so tantalizingly defy explanation.

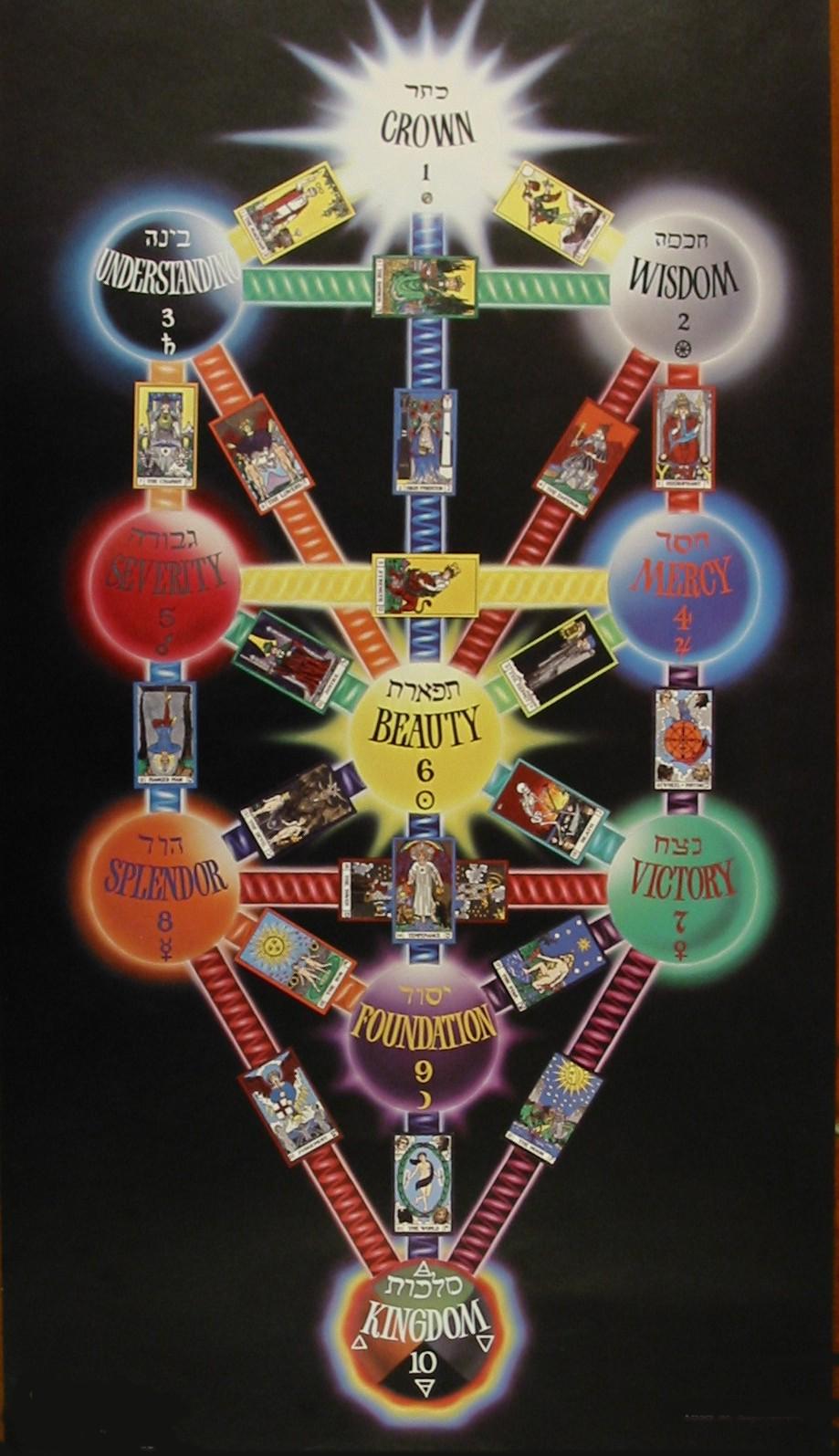

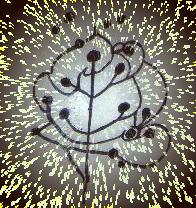

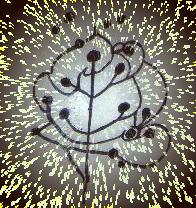

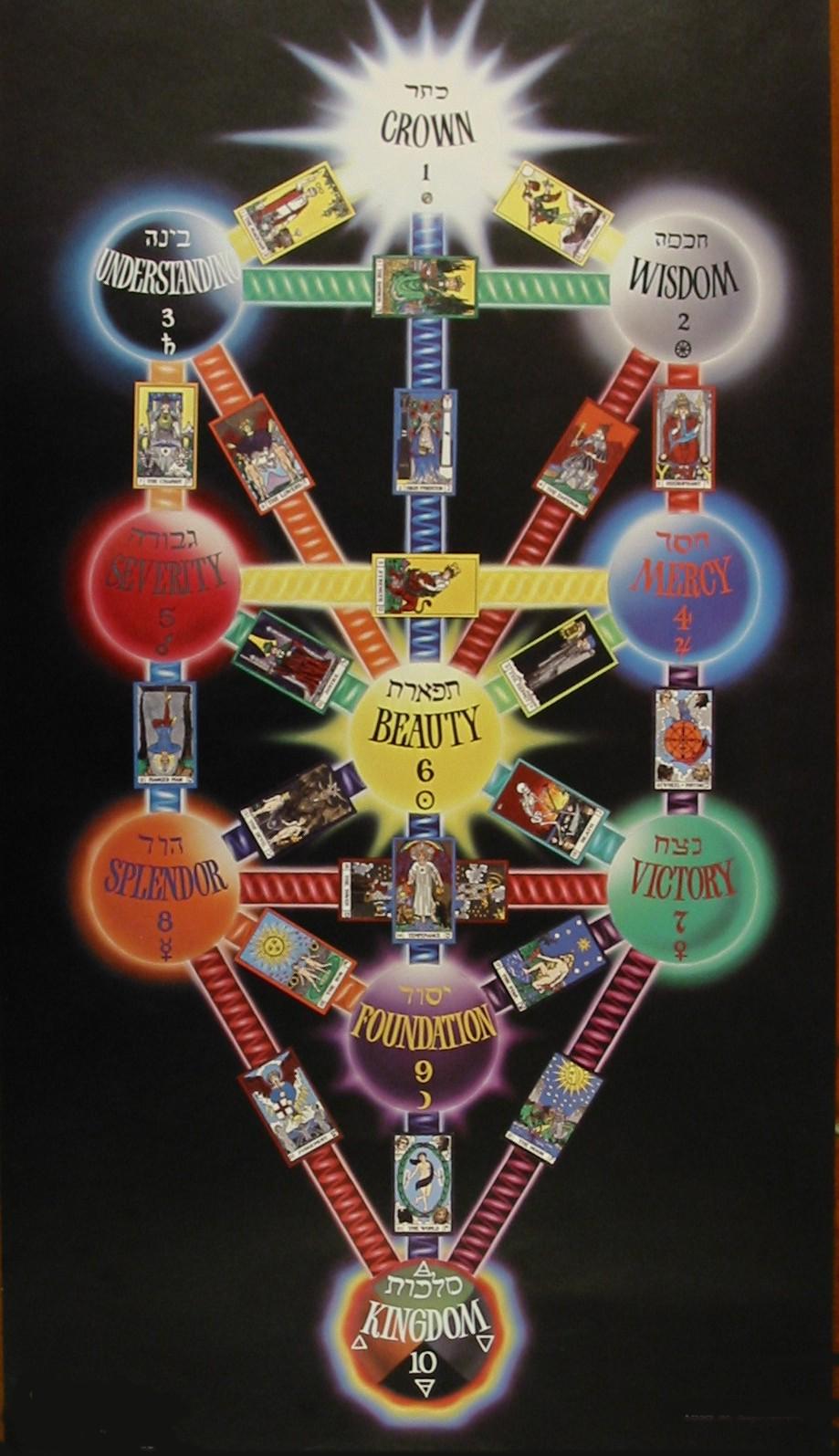

For an adequate interpretation of this knotty puzzle we must come slightly forward in time from prehistory and consider the occult teachings of the Cabbalists, who made their influence felt in 12th century Spain. The Cabbala is a Jewish mystical system which according to legend had its origins in the secrets which were transmitted to Moses on Mount Sinai. Cabbalism is closely tied up with the Hebrew alphabet, and (as with the runes) each letter is given a mystical significance. Cabbalism is a 'hidden teaching' behind orthodox Judaism, and central to this teaching is the idea of how the 'unknowable' Godhead manifests itself within the fabric of human perception. This concept is symbolically expressed as ten different stages, known as SEPHIROTH. These are laid out in a geometrically significant pattern linked together by twenty two channels or 'paths'. Completed, the design represents an 'Anatomy of the Deity', whose 'garment' is the Universe. This 'Anatomy' may be equated with the 'Burning Bush' from which the Lord spoke to Moses. It is known as 'The Tree of Life'.

The Ten Sephiroth (see diagram) are set out in three vertical columns. The left hand column is feminine and the right hand one masculine, while the central column pulls together and holds in balance the first two. The first three Sephiroth are known as the SUPERNALS and symbolize a kind of 'Nirvana' state where wisdom and understanding dwell in enlightened harmony. Far beneath them hang the SEVEN SPHERES, those manifestations of divinity which may be readily perceived by the human mind. Read in reverse, the 'tree' becomes a source of 'Spiritual Exercises', a series of 'paths' which may be followed, the ultimate long term achievement being a state of 'oneness' with God.

The 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet correspond to the 22 'paths' of the Tree of Life, and 19th century occultists have equated these paths withy the 22 trumps of the Tarot pack, the symbolism of the cards being supposedly derived from that of the Hebrew alphabet. Certainly the images in the Tarot cards do suggest some kind of 'pilgrim's progress', a journey along esoteric paths.

"Elementary my dear Watson!" One is tempted to say, but there are, unfortunately, a number of snags. When we compare the cabbalistic Tree of Life with our prehistoric rock carving certain anomalies emerge. The two designs are not identical for one thing. Although obviously similar in overall meaning, they differ in the detail; and it is not too hard to understand why, for culturally and historically, the two symbols are worlds apart!

Whoever carved the Tree of Life Stone was certainly not a Jewish Rabbi! More likely he (or she) was a pagan 'proto celtic' shaman, a forerunner of the Druids. So where did the peoples who inhabited prehistoric Britain get the symbol from? It seems unlikely that they knew the ins and outs of Mosaic Law! Of course, it could be argued that the Jews got the symbol from the Celts, it depends on your scholastic point-of-view! There is however, a single, admittedly very tenuous, link between the Celtic and Semitic worlds, and the catalyst of this connection appears to be the Iberian Peninsula. The Megalithic culture that built Stonehenge was reputed to have come from Northern Spain, and many centuries later, the 'Beaker' Folk (who were proto-Celts) possibly came from that direction also. By what we call the 'Iron Age', Britain had become a loose confederation of warring tribes, and what is now Northern England was a part of Celtic Brigantia. These peoples not only inhabited Britain, but could be found all over Europe, both outside and within the boundaries of the Roman Empire, particularly in Gaul and Iberia (Spain). The origins of the Celtic tribes are obscure, but are, nevertheless, hinted at in the myths and legends of the Irish; for while the Roman Occupation of Britain effectively destroyed the power of the Druids, along with their store of Celtic history, tradition and legend, the old stories of the Irish bards remained unmolested, and, after centuries of oral transmission were eventually written down.

These legends speak of the many races who colonized Ireland back in the mists of prehistory. The motherland of these peoples was usually Iberia, although Greece and Egypt also claim the honour. (One ancient Irish race, the Dravidians, reputedly came from India!) Of these ancient migratory groups, two of them, the 'Tuatha De Danann' and the 'Milesians' are particularly interesting.

The 'Tuatha De Dannan' (ie the children of Danae, or Danu, the Moon Goddess) lived at first in the "northern isles of Greece". They knew "lore and magic and Druidism and wizardry ande cunning". For a while the Tuatha "went between the Athenians and the Philistines" in a diplomatic capacity; but, being descended from another Irish race, the Nemedians, who had returned to Greece, the Tuatha dreamed of reclaiming the land of their forefathers, which they eventually did. In a great fleet of "speckled ships" they returned to Ireland, where they landed on the first of May, the first day of summer. There they overcame an earlier ancient people, the Fir Bolg.

For a while the Tuatha ruled Ireland unmolested, but eventually they in turn were invaded by yet another Celtic tribe, the Milesians. One legend attributes the removal of Ireland's snakes to them, many centuries before St Patrick was accredited with the act! According to the story the Milesians dwelt in Egypt, and it was there that one of them was cured of a snakebite by no less a person than Moses! Moses promised the Milesians that his people would come to a "fertile land never to be defiled by snakes". One of these 'Egyptian Celts' was to marry Scota, the Pharoah's daughter, who was to give her name to Ireland. (The old name for Ireland was 'Scota Magna', modern Scotland being then 'Caledonia'. Scota was later to give its name to 'Scotland' in the same way that 'Angeln' in Denmark was to give its name to 'England'.) In the end the Milesians went out of Egypt into Spain, from where they eventually migrated to Ireland, where there were no snakes!!

Fantastic? Improbable? Maybe so:- but if there is any truth at all to these legends then we have a direct connection between Celtic Britain and the Semitic cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean. Furthermore, the link becomes even less tenuous with the arrival of the early Christian Era. It is well known that Christian Hermits were living in the West of Ireland within a century of the crucifixion, and it is equally well known that the early Celtic Church owed its allegiance not to Rome but to Alexandria and the Egyptian Coptic Church, its lines of communications passing down the Atlantic seaboard, via Iberia to the Eastern Mediterranean. The Coptic Church was (and still is) much closer to the Judaic Nazarene/Essene roots of Christianity than the Western Roman model. The development of cabbalistic teaching in 12th century Spain may only be co-incidental to the plot, possibly being in part stimulated by Moorish/Islamic culture, which unlike mediaeval 'Christendom', had done much towards preserving the knowledge of the 'Ancient World'. Be that as it may, the deeper we delve into this complex subject, the less surprising it seems to find an ancient Hebrew symbol carved in 'cups and rings' on a Yorkshire Moor!

The shape of the Tree of Life Stone, though stylized in a Celtic rather than a Jewish way, is, nevertheless, more reminiscent of the 'burning bush' than its more highly 'evolved' cabbalistic counterpart. Yet again the cups and rings express 'form' in a unique and highly naturalistic manner. The Beltane fires, the struggle between summer and winter, life and death, good and evil, all are expressed in a mysterious way upon Snowden Moor; and central to the whole idea is the 'Tree of Life':- the sacred rowan, the Burning Bush; the 'divine matrix' which keeps these cosmic polarities in a state of equilibrium and harmony.

Of course behind the whole concept of the 'Tree of Life' is the idea of God, who is seen as the creator of everything, physical and spiritual. The Celts, you will argue, were pagans who worshipped numerous, often quite savage, deities. They were not monotheistic, like the Jews. This is true of course, yet I do feel that we, as 'civilised' people do tend to underestimate the sophistication of pagan beliefs. What the Druids believed was not dissimilar to what Hindus believe today, and some schools of thought maintain that both belief systems have a common origin. Certainly there was a 'Pythagorean Transmigrational' element to pagan Celtic beliefs about life after death, a belief which we have already encountered on our journey.

We have also observed that the Celts were quite familiar with that most Hinduistic of symbols, the swastika, or sun wheel. We have already seen that each 'sphere' on the Tree of Life represents a spiritual force at work in God's universe. Now if we were to give each sphere a name, a nature, and enshrine each one as an independent 'sub-deity' in its own right, we have effectively turned the Tree of Life into a pantheon of pagan gods!

'Binah', for example, which is both a feminine and a negative principle, would, in pagan Celtic terms, be associated with Danu, the Moon Goddess. The others you will have to work out for yourself!

The Druids, (like Shylock) had eyes, hands and senses the same as anyone else.They, like most polytheists today, could perceive the idea of a 'Creator God' who made everything, including those lesser deities which they worshipped in their daily lives, deities which presided over the sunshine, the moonlight, air, earth, fire, the wind and the rain. The pagan argument was simply that the 'God of Gods' was so remote and mysterious as to be unreachable, so instead they worshipped (and humanized) his more understandable manifestations. Of course the Jews, when they adopted monotheism, simply went 'upmarket'! Their great achievement was to eliminate the unnecessary and the superfluous, just as the Buddhists were to do in Asia in an even more radical way. As for the forces of good and evil, they could be laid at the door of those 'angels and ministers of grace', God's servants carrying out his divine and mysterious plan. The monotheistic premise was brilliantly simple:- why deal with the minion when you can talk directly to the boss!?

Thus it is clear that the idea of the Tree of Life makes sense in the context of both types of religion. Perhaps here, on this remote Yorkshire moor we are looking at the first truly universal religious symbol, a 'missing link' between the beliefs of ancient religions and those of Judeo/Christianity. On this tree, depicted in geometrical, hierarchical form, are all those mysterious unconscious instincts which both afflict and irradiate the human spirit, a symbol of the one God and the Many, of one person and of all humankind. A truly universal symbol.

The plaintive cry of a lapwing circling overhead disturbs our reverie, and we are brought back to the mundane with a bump! Who knows? Perhaps the bird is Margaret Thorpes 'familiar' searching for the Beltane Feast! It is now late in the day, and Otley beckons.

Other 'cup-and-ring' carvings exist on Snowden Moor among the mounds of an extensive Bronze Age cemetery. (One of these stones is a 'deaths head'). There is also evidence of stone circles used for ritualistic purposes and near the Askwith Road is a standing stone known as the 'Old Man of Snowden'. (The word is derived from the Celtic 'maen' meaning 'stone'). Whatever the reasons, Snowden Moor was undoubtedly a place of deep religious significance in prehistoric times, and in view of this it is perhaps surprising to discover that the area is not covered in the County Council's otherwise comprehensive gazetteer of carved rocks. So, though bounded by roads, the bare expanse of Snowden Moor still remains aloof and apart, carefully guarding its secrets, the wind its watchtower and the moorland birds its sentinels. It is time to move on.

Descending the path back down to Snowden Carr Road, we take in what is to be our last 'high level' view of the Washburn Valley. Prominent in the near distance is the highly distinctive BT radio communications tower at Hunterstones. This mast, standing atop a tree covered hillside, is a prominent landmark which may be seen for miles around. Below it, to the left, we can see the great concrete dam of the Thruscross Reservoir. The dam was constructed in 1966 and can hold some 1725 million gallons of drinking water. From it water is piped through the Eccup Reservoir to supply the city of Leeds. (The other Washburn reservoirs by the way, are Thruscross, Fewston and Lindley Wood).

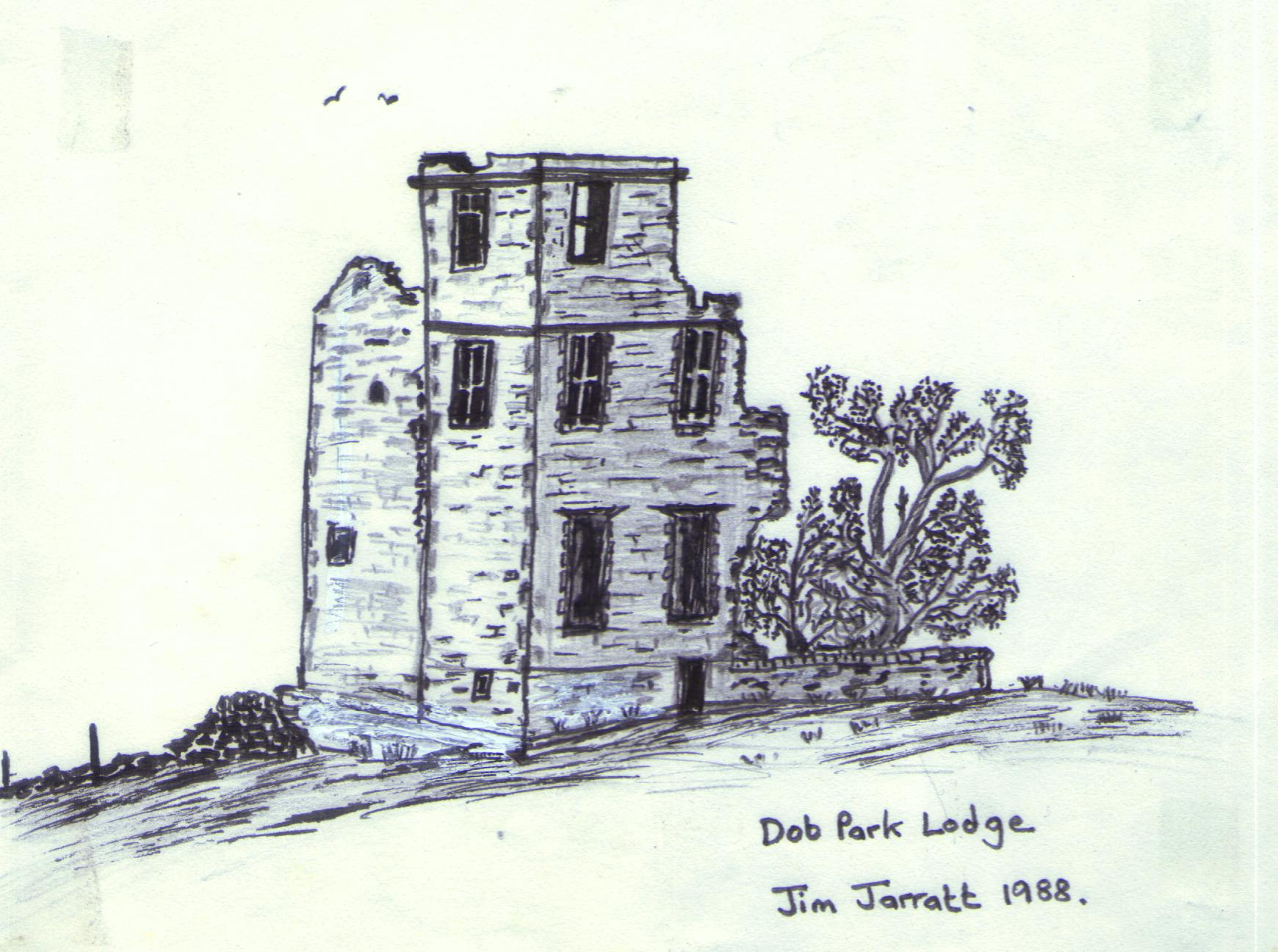

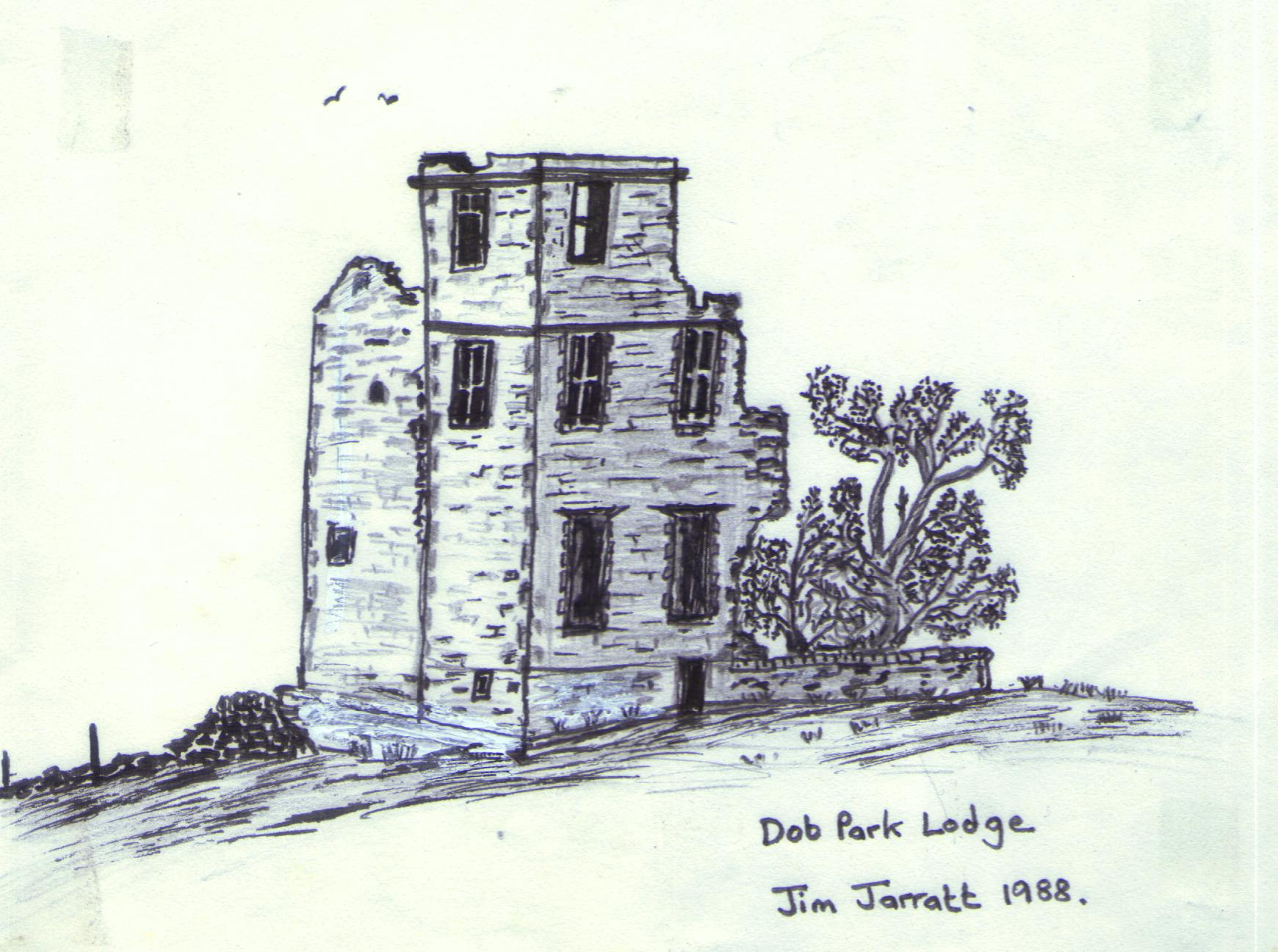

On reaching the Snowden Carr Road we bear right along it, eventually following a track which bears left down to Midge Hall Farm. From there a route leads along the top edge of the woodlands to Dob Park House, passing the ruins of Dob Park Lodge en route.

Dob Park Lodge, (originally called 'Dog Park Castle'), is, like Barden Tower near Bolton Abbey, or Norton Tower near Rylstone, the remains of a mediaeval 'Hunting Tower', a place where dogs were kenneled and feasts held in the days when the surrounding lands were the 'parks' or hunting reserves of great families like the Cliffords, or, in the case of Dob Park the Fawkes, Gascoignes and Fairfaxes. There is a curious legend of buried treasure associated with Dob Park Lodge. The story goes that a local farmer passing by the lodge one evening, discovered the entrance to an underground passage. Plucking up his courage, he went inside and on reaching the end of the tunnel suddenly found himself in a brightly lit chamber, in the centre of which was a chest surmounted by a chalice and a two handed sword. Approaching the chest, the farmer discovered to his horror that the chest was guarded by a Barguest (Anglo-Saxon 'bar geist'-'guardian spirit), a great black hound with flaming eyes as big as saucers. The hound (very clever pooch this!) spoke to him, inviting the farmer to either taste the cup, pull the sword from the scabbard or open the chest. The farmer tasted the cup and it scalded his mouth! As he ran around gasping for water, he saw the sword withdraw itself from the scabbard and the chest begin to open....at which point the lights went out! When the farmer, no doubt after an eternity of blind panic, finally got back out into the cool night air, he discovered to his horror that his hair had gone white! He fled from that accursed place and the treasure (like that beneath Alderley Edge and Richmond Castle) still awaits discovery.

Beyond Dob Park House, (which the path goes around) we bear to the right, and soon the distinctive skyline of Otley Chevin appears before us, Otley itself being hidden out of sight in the valley below. Otley Chevin is 935 feet above sea level, and its name comes from the celtic 'Kefn' meaning 'a ridge'. The Chevin was enclosed in 1779, and most of its rocks have since been obscured by afforestation. Some quarrying has taken place down the years, Otley stone being used in the foundations of the Houses of Parliament. Along with Snowden Carr, Baildon and Rombald's Moors, the Chevin is yet another 'field' of Bronze Age rock carvings.

On reaching the main road by the TV booster mast, just beyond Higher Carr, a well signed path leads over fields to Haddock Stones Farm. It is very tempting here to forget Haddock Stones and to continue along the main road to Otley - after all, it's only two miles to Otley Bridge and it's downhill all the way! The Beacons Way, which heads for Farnley Church adds another couple of miles on to the distance, so if you are tired and the light is failing you will find this chance of a shortcut down into Otley very hard to resist! (You will resist it though.......wont you?)

Farnley Church is a Victorian reconstruction of a Norman Church. (Some of the original Norman masonry is incorporated into its fabric). It is furnished mainly by Thompson the 'mouse man' of Kilburn, and some of its glass came from nearby Farnley Hall which was painted around 1800 by JMW Turner (who also painted Bolton Abbey). Its striking west window was executed by Trevor Long.

Nearby Farnley Hall also has strong associations with Turner, who stayed there as a guest of Squire Fawkes, while making drawings for Dr. Whitaker's 'History of Craven'. According to one local story, Turner used Otley Chevin as a model for the 'Alps' in a painting depicting Hannibal and his elephants! Farnley Hall also has associations with the Fairfaxes. There is a stone garden table there where Cromwell, 'Black Tom' Fairfax and his uncle Charles are reputed to have planned the Battle of Marston Moor. The hall is not, alas, open to the public.

So at last, passing by the long weir and the pretty park with its lido and bowling greens, we finally approach Otley Bridge and the end of our journey. The Wharfe is grander hereabouts than it was in Addingham, but it is no less charming. Rowing boats ply its clear waters, and the atmosphere is one of pleasant relaxation. Section 4 of the Beacons Way ends at the bridge and the bulk of Otley lies beyond it. From here you could, if you so desired, follow the Ebor Way to the Towers of York Minster.

On reaching Otley your prime aim will be to secure food, drink, accommodation or a bus home! You are unlikely, after the rigours of the Beacons Way, to feel like exploring Otley, but please do so if you get the chance!

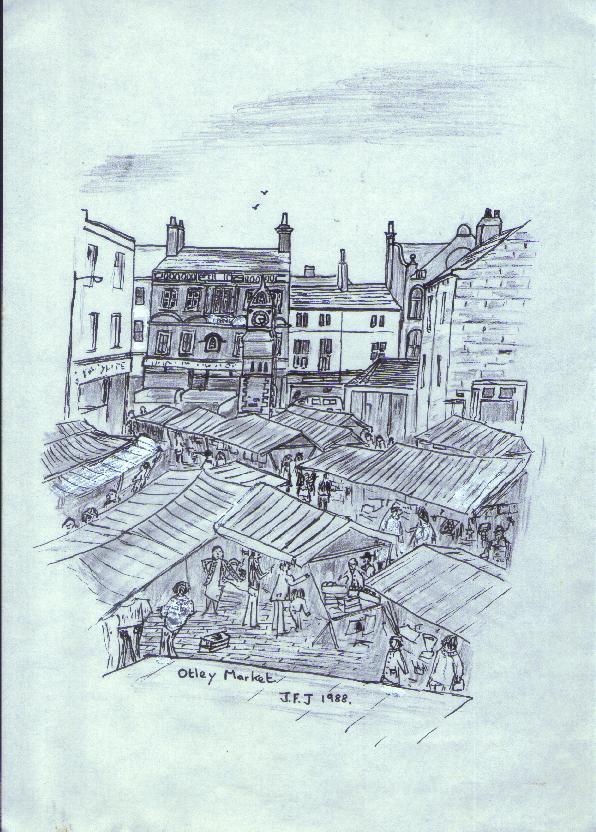

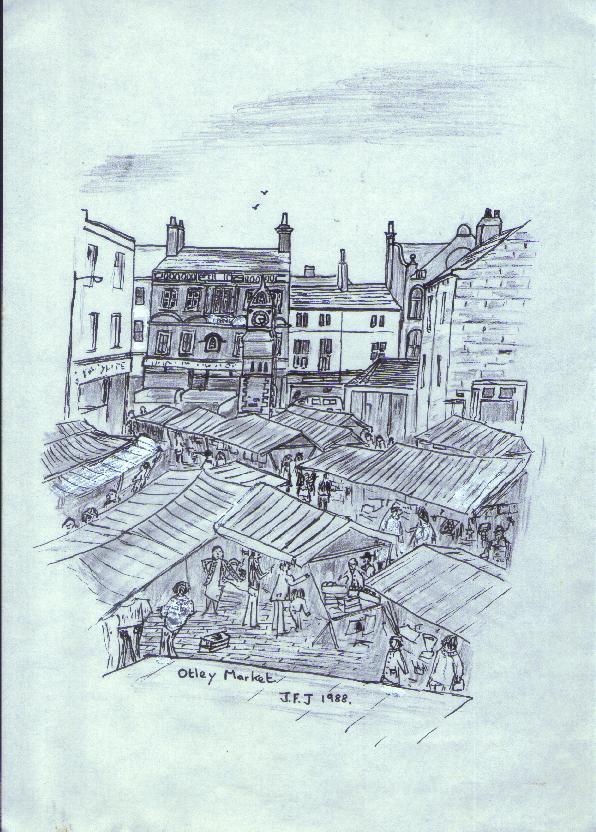

Otley is a charming town. Very much a part of West Yorkshire, it has, nevertheless, the 'feel' of a dales market town. It is, despite the industry which girdles it, very much a'country' sort of place. Its cattle market is well known, and its annual agricultural show is famous. Otley received its market charter from Henry II in 1222 and today, despite the busy traffic which rumbles all around it, Otley Market still has a mediaeval character, as its tumbledown stalls line the sides of the main street and cluster around the Buttercross and the Jubilee Clocktower.

Otley's church, All Saints, has memories of distant Whalley. The first church here was established by King Edwin of Northumbria and Paulinus around A.D. 627, and contains fragments of numerous Anglo-Saxon crosses. Parts of the church exhibit Norman masonry and its tower is 14th century. All Saints has lots of monuments, and it should come as no surprise to discover in the south transept the grave of Sir Thomas Fairfax, (Edward Fairfax's elder brother and 'Black Tom's' grandfather), along with that of his lady, Helen Aske. Together they slumber in the company of a host of Fawkes' and Vavasours. Outside in the churchyard we discover a scale model of the entrance to the Bramhope Railway Tunnel, a monument to the navies who were killed during its construction in 1845-49. Here at All Saints was also baptized Otley's most famous son, the cabinet maker Thomas Chippendale (baptized 5th June 1718). A modern statue of Otley's 'great man' stands outside the old Prince Henry's Grammar School, founded in 1611, which he once attended. (The present Prince Henry's has since moved to rather more substantial premises on the other side of the river.)

So now at last, standing above the ribbed arches of Otley's fine old mediaeval bridge, we watch the deep waters of the Wharfe swirl gently beneath our feet. We have reached the end of our journey. Here at Otley, the start of our adventure in distant Whalley could well be on another planet! In our travels we have walked from the Ribble to the Wharfe, from Lancashire into Yorkshire, and the limit of our view has ranged from Blackpool Tower to the Kilburn White Horse. Now at last our journey is complete and we can look back, hopefully with some degree of self satisfaction. On the Beacons Way we have travelled through time and space. Of witchcraft, earth magic and religion we have had a surfeit, but hopefully we have gained some insight and understanding as a result. We came, we saw, but we did not conquer, for so many of the places we have seen invite further exploration and await our return. Together we have shared a journey which must, like all journeys inevitably reach its destination and come to an end. Other paths await, and it is time for us to go our separate ways to seek out new beginnings and new adventures, for:-

"Our revels now are ended. These, our actors,

As I foretold you were all spirits, and are

Melted into thin air, into thin air......................."

JIM JARRATT. 1988.

BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE

Copyright Jim Jarratt. 2006

"All under the leaves and the leaves of life,

I met with virgins seven,

And one of them was Mary mild,

Our Lord's sweet mother in heaven...."

TRADITIONAL EASTER CAROL

"From Penigent to Pendle Hill,

.........And so the curtain rises on Addingham , the start of SECTION 4 and the last watering hole before the end of our journey in Otley. 'Long Addingham' at first sight appears to be something of a nineteenth century upstart, its narrow, winding main street being quite hemmed in by an assortment of houses, shops and mills. It is faintly reminiscent of Cornholme near Todmorden, or Denholme near Bradford, along with all those other semi industrial linear villages which have the misfortune to have busy arterial roads running through them. Addingham's main street has long been an exhaust choked rat run, a constricted winding nightmare to motorist and pedestrian alike. Heavy lorries rumble round its thirteen successive bends and pedestrians tend to meditate upon the meaning of life before crossing the street! Lately however the A65 has bypassed the place and the traffic pressure has eased.

Mercifully though, Addinghams' apparent ugliness is merely skin deep. We have already seen the tranquillity of Addingham Moorside and will shortly encounter the charms of its 'Wharfeside' as we cross what must perhaps be the most romanticised river in Northern England. Addingham in fact stands between river and moor, belonging to neither, but a gateway to both. The Dales Way runs along the riverside, and on reaching Bolton Bridge (just upstream) enters the Yorkshire Dales National Park. As if to supplement this, paths fan out from Addingham in all directions.

Addingham does have a history, which began long before the age of mills and industrial upheaval. Within a few minutes of the main street we can enjoy the serenity of St. Peter's Church, which is believed to have been founded in the Dark Ages after one of St. Aidan's missions. The church is built on a mound, and some writers have suggested that this was the site of a 'druid temple', for according to one local source the outline of the ancient circle becomes quite distinct after a light sprinkling of snow. (As if to add to this mystical atmosphere a cutting from the famous Glastonbury Thorn was planted in the churchyard some years ago).

To corroborate Addingham's ancient origins there is also a fragment of an Anglo-Saxon cross, and it is also known that there was a settlement here around 876, when the Danes, who attacked York by sailing up the Ouse, forced the (then) Archbishop to flee and seek refuge here. This raises an interesting question:- why Addingham?? We can only speculate of course, but one possible explanation might be found in the location of Anglian 'national' boundaries. Prior to the incursions of the Viking Age Northern England was inhabited by two different ethnic groups:- Mercians and Northumbrians. Although both nominally 'english' the two groups were culturally different, and their royal houses, descended from Penda and Edwin respectively, had long been mortal enemies. The Mercians ruled over what is now the Midlands, but Mercian rule extended into Pennine West Yorkshire. A religious difference also existed at one point, for although the whole of Northern England was Christianized prior to the Viking Age, the earlier part of the Anglian period had seen the Northumbrians embracing the new faith while the Mercians remained staunchly pagan. With the fall of Edwin, the star of pagan Mercia rose high, and, uneasily allied with the Celts, they swept into Northumbria, even sacking York itself. This triumph was not complete, however, and it was not long before the Northumbrians reasserted themselves, and the two kingdoms existed uneasily side by side, right down to the arrival of the Danes.

The evidences of these two kingdoms (chronicles apart) are drawn from the distribution of place names, which infers that the original line of separation between the two kingdoms ran down the Aire Valley. South of the Aire, for example, the Northumbrian 'borough' as in 'Knaresborough' becomes the Midland Mercian 'bury' (for example Dewsbury or Stanbury). The place name element 'Worth', so common around Keighley, is Mercian in origin, and is not found in Northumbrian Wharfedale. Here then, was a 'national' boundary, an ethnic border beyond which the people would have felt loyalty more to the Kings of Mercia than to their Northumbrian enemies in York (Eoforwic). Times change, but even in times of peace bitter memories die hard. Perhaps this is why the Northumbrian Archbishop, seeking refuge from the Danes, chose to flee no further than Addingham, perhaps imagining that he might receive a cooler welcome 'over the hill', where men spoke with a Mercian dialect.

The last Viking terror to sweep across the North was instigated by William I., the 'Nor(th)man', for after the Conquest, and the fierce resistance to it by the peoples of the North, Addingham, along with the rest of the district was 'laid waste'. In the Domesday Book it is described as 'Terra Regis' ie- 'belonging to the king', who had taken posession of it along with the rest of Earl Edwins pre-conquest lands. In the general carve-up which ensued the Manor and Advowson of Addingham was eventually granted to Mauger De Vavasour by Robert De Romille towards the end of the reign of Henry III. It was to remain in the possession of the Vavasours from 1279 to 1714.

Like most communities in the area Addingham undoubtedly suffered on occasion from the depredations of the Scots who swept repeatedly down the Dales throughout the Middle Ages. Each summer they would come looting and burning, often forcing the Prior of Bolton and his Canons to seek refuge in Skipton Castle. After Bruce's triumph at Bannockburn there was no holding them, but when they eventually met their 'Waterloo' at Flodden Field in 1513, the Scots came no more, and the revenge of the Dalesmen was complete. Addingham, like many other villages in Craven sent its contingent of soldiers with Henry Clifford, The 'Shepherd Lord', to meet the Scots.

From Linton to long Addinghame,

And all that Craven Coasts could till

They with the lusty Clifford came......."

And years later, when the Scots were but a distant memory, there came a new invasion:-of mills and machines. The Industrial Revolution had arrived in Addingham.

The creation and development of the textile industry in Addingham was largely due to the Cunliffes, forebears of that famous Lister family who built the great Manningham Mills complex in Bradford, and played such an important role in the industrial and political development of that city. (Samuel Cunliffe Lister, the Ist Baron Masham, who knew Addingham well, is buried in his family's vault here). The Listers had at least three mills in Addingham, and had the village been easier of access it is quite probable that they would have built a massive industrial township here, which would surely have done little to enhance the charms of this part of Wharfedale! The earliest textile industries in Addingham were, of course, cottage based, and many of the houses crowding Addingham's main street were built with an extra storey to accommodate the handlooms, sometimes being dubbed 'Addingham's Skyscrapers'! This prosperous period of domestic weaving came to an abrupt end, however, with the advent of the machines, which brought unemployment, hardship and poverty to large numbers of workers, who found their traditional skills rendered obsolete virtually overnight! The change was not to be welcomed in Addingham.

In 1826, when the Listers sought to install the new power looms in Low Mill, close to the Wharfe, the spirit of Luddism reared its head and they were hotly opposed. The mill was attacked and the rioters had to be dispersed by the military. One of the rioters, who fell into a cesspool whilst trying to climb into the mill was fatally smothered. In the end of course, progress was unstoppable and the mills reigned supreme; but this supremacy too was fated to come to an abrupt end with the recession of the industry in the early 1960's, when the mills closed down, along with Addingham's now completely vanished railway link.

Leaving Addingham, we head for the little suspension bridge that crosses the Wharfe on the far side of the village, near the Dales Way. The existence of this little bridge was of vital importance in the planning stages of the Beacons Way, for at that time I was unsure as to whether or not there was a crossing of the Wharfe at Addingham. I had, in fact, to make a preliminary visit here, before starting on the Beacons Way, just to make sure that the bridge was there! I was greatly relieved to discover this secluded crossing, with its pleasant, tree-shaded path heading off in the direction of Beamsley Beacon. It gave the 'green light' to the whole idea.

The Wharfe is a famous and a beautiful river. Here at Addingham it looks so peaceful, its clear, trout filled waters sliding gently over its boulder strewn bed. Midges and flies hover over the water and anglers sit on the velvet green turf and shingle banks, lost in a world of their own. Compared to the brooding, sullen waters of the Aire, it seems a world apart, but yet it is perhaps wise to remember the old saying:-

"Wharfe is clear and in the Aire lithe,

Where the Aire drowns one, the Wharfe drowns five."

The Wharfe is, in fact, a notoriously treacherous river. The story of the Boy of Egremond who was pulled back by his hesitant hound while trying to jump the seething waters of the Strid needs no further elaboration here, save to say that this notorious bottleneck of the Wharfe is but a few miles upstream from this gentle spot. It is a river of changing moods. Fierce rapids and gentle pools often lie in dangerously close proximity, and the onset of a sudden rainstorm can quickly swell this innocent looking stream into a torrent of alarming proportions. Potholers visiting the upper reaches of the Dale watch the Wharfe carefully, for its level, combined with the local weather forecast is often used as a yardstick by which to measure their chances of subterranean survival! Being fed by so many underground streams, the Wharfes moods can change very quickly, as I once discovered when I picked the wrong night to camp by the river near Kettlewell Bridge! Yet the Wharfe is still beautiful. Even if it is a wolf in sheeps clothing, that wolf certainly knows how to dress!!

From the Wharfes' meadows our route meanders up the hillside toward Beamsley Beacon. Between leaving West Hall Lane and rejoining the metalled road at Beech House, we follow a most attractive bridle path which in summer is not only a dense jungle, but also a paradise for the amateur botanist. When I came gasping and sweating up this path on a hot summer's day I could not help but notice the simply phenomenal array of wild herbs, shrubs and flowers. Here is a list containing some of them:-

GREATER BELL FLOWER (Campanula latifoliae) Flowers July.

BETONY (Betonica officinalis) Flowers June- September

GOOSEGRASS or CLEAVERS (Galium apirine)

MEADOWSWEET or DROPWORT (Filipendula ulmaria) Smells like marzipan. Contains vanilla!

NIPPLEWORT (Lapsana comminis) flowers-July to September.

PINEAPPLE WEED (Matricaria matricarioides) Bitter, rank smell.

RATS TAIL PLANTAIN (Plantago major)

HERB ROBERT (Geranium robertianum)

TUFTED VETCH (Viccia cracca) distant relative of the garden pea!

FOXGLOVE (Digitalis purpurea) Poisonous. Used to treat heart disease.

RED CAMPION (Silene dioica)

NETTLE (Urtica dioica) stings!

ROSEBAY WILLOW HERB (Epilobium augustifolium) Purple pest!

HOLLY (Ilex aquilifolium) Female (as you should know!) has red berries.

HAWTHORN (Crataegus monogyna)

WILD OAT (Avena fatua)

Passing this way armed with a reference book, you would no doubt discover even more plants than I did. The meadowsweet, I recall, was particularly delightful, and even now as I write, months later, I can still smell the sweet marzipan aroma rising from a specimen pressed in the leaves of my notebook! Once smelt, the plant is never hard to identify thereafter.

Now at last, we come to our third and last beacon:- Beamsley Beacon or, as it is sometimes known, Howber Hill. The summit of the Beacon is 1300 feet high and is capped with Kinderscout Grit. It commands the surrounding countryside and offers some good views, particularly in the direction of Bolton Abbey, where the ruins of the Augustinian Priory (it was never an 'abbey') can be seen in the distance.

Like Pinhaw Beacon, Beamsley Beacon does not lie too far from the metalled road which runs past it down towards Bolton Bridge; and, (also like Pinhaw) it once had a guard hut on the Beacon which was built and manned in Napoleonic times to warn of French invasion. There the resemblance ends, however, for Beamsley Beacon has credentials rather more impressive than those of its humble neighbour. Capped by a rocky cairn and a concrete triangulation pillar, it is an impressive rampart of boulders and scree. It is, in fact, the best eminence we have encountered since leaving the summit of Pendle, and the burnt stones on the summit cairn testify to its recent use as a beacon site, probably asw part of the 1988 Armada celebrations.

Beamsley Beacon is a very ancient landmark. Its alternative name of Howber Hill testifies to its antiquity, being derived from the anglian 'how' (burial mound) and 'ber(g)' meaning 'hill' or 'fort'. Other explanations have also been hazarded:- it could, for example, be derived from the Anglo-Saxon 'heawan' meaning 'to view', although I personally favour the first explanation.

Whether or nor Beamsley Beacon was ever actually used as a fortress is uncertain, but there is little doubt that it was used as a prehistoric cairn burial site, for no Beaker community would leave such a fine viewpoint as this 'untenanted'.