THE

FIELDEN TRAIL

SECTION 4.

Todmorden via Basin Stone,Withens Gate, Stoodley Pike, Mankinholes and Lumbutts

Now at last we come to the final (and wildest) section of the Fielden Trail. The going from

here on gets tougher, the route becoming a high level traverse along the edge of the

watershed from Gaddings to Stoodley Pike Monument, via Withens Gate. If the weather

is awful and you are badly equipped and/or tired then this is the time to think about that nice

cosy car parked down in Todmorden. Remember it's not too late (yet!). If however you

have walked all the way from Stansfield Hall and have set your heart on doing 'the

whole thing' well, let's get going then! If on the other hand you are starting Section 4

'fresh', here are the directions to get to it. from Fielden Square follow the Calderdale

Way past Shoebroad, then follow the track up to Lumbutts Road. Turn left to the

Shepherd's Rest. Go through the gate opposite and bear right to the walled lane heading up

the moor. This leads directly to Rake End, which is on the edge of the moor, along the

causey.

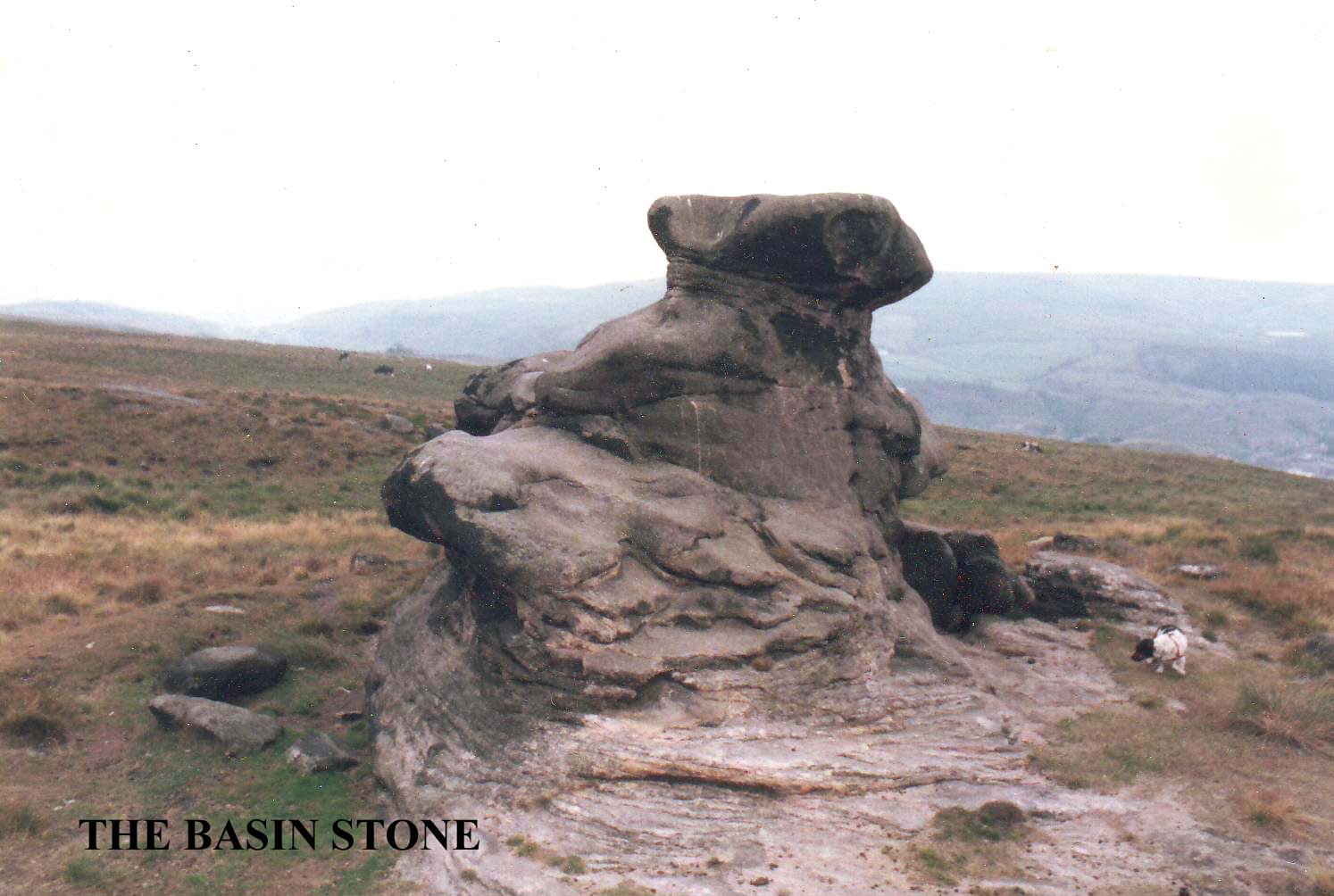

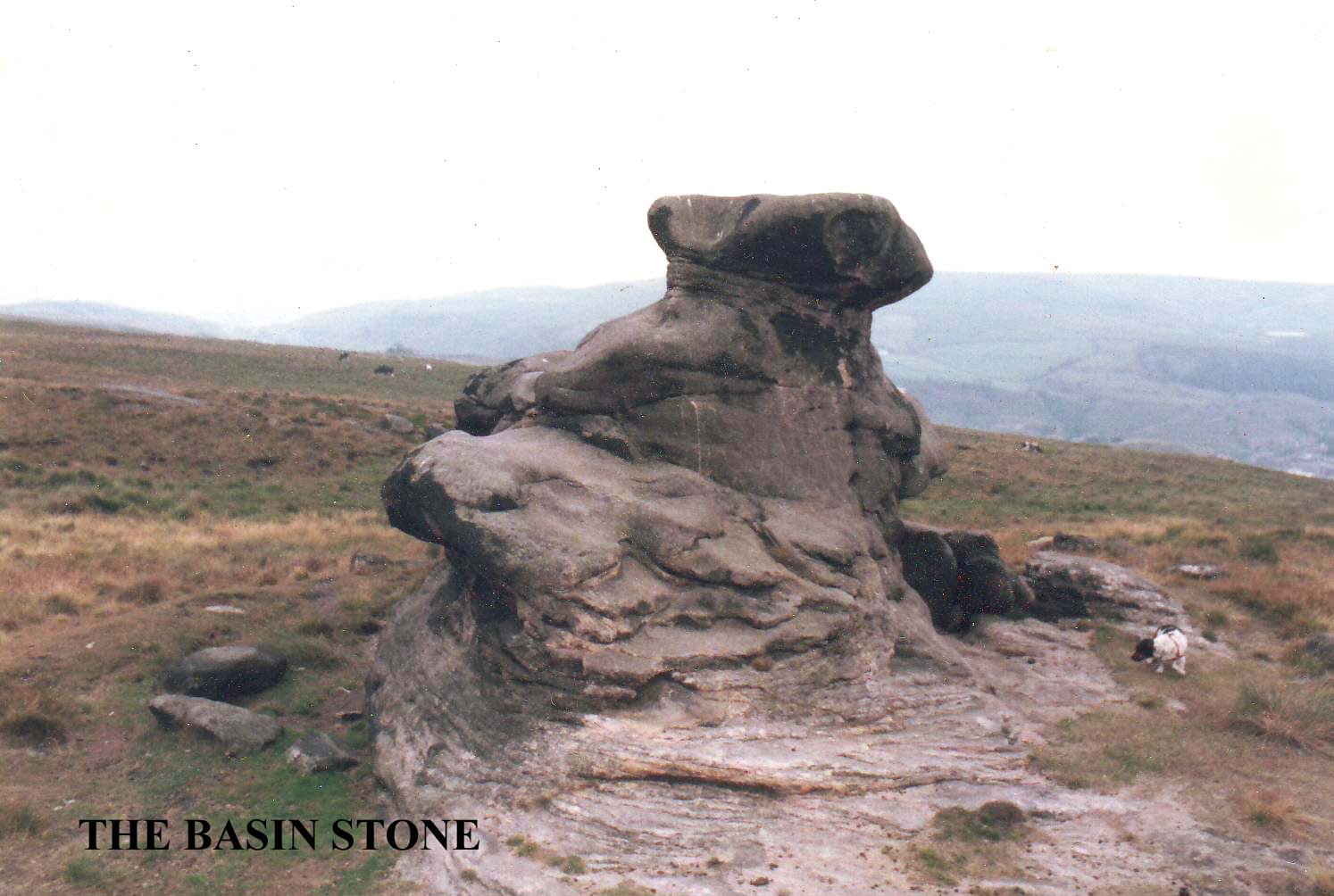

After leaving Salter Rake Gate follow the path up the moorside to the Basin Stone, which

is quite unmistakable.

The Basin Stone.

A giant stone mushroom, the Basin Stone affords an excellent view over the Walsden Valley.

Nicklety and Inchfield, encountered earlier, may be seen across the valley. This bizarre rock

formation is the result of natural erosion, centuries of scouring by wind and rain. The Basin

Stone looks almost like a pulpit, and it is perhaps not surprising therefore to discover

that it has, on occasion, served exactly that purpose. Wesley is reputed to have preached

here, and although I have found no evidence to give truth to this story, I would not be in

the least bit surprised to discover that he had. Wesley certainly had a penchant for moorland

crags as his initials carved on rocks at Widdop testify.

Evangelism was not the only force to beckon crowds of people to these remote

moorland fastnesses. There were other, more secular causes to be fought for. The

year 1842 saw considerable industrial and political unrest. In the summer of that

year there was a general mill stoppage throughout southeastern Lancashire. Those

on strike were determined to stop others from working, and on Friday morning the

12th of August a mob of men and women marched from Rochdale to Bacup, armed

with hedge stakes and crowbars, and continued onwards towards Todmorden. Every

mill en route was visited, the fires raked out and the plugs drawn from the boilers.

Shopkeepers and innkeepers were forced, under threat of violence, to 'donate' bread

and ale. The agitators or 'plugdrawers' visited Waterside Mill, where Fielden's

operatives were actually receiving higher wages than the plugdrawers themselves

demanded. No opposition was offered, but special constables were sworn in

and Hussars from Burnley were quartered in Buckley's Mill at Ridgefoot. The

plugdrawers marched on Halifax, where, 600 strong, they joined a contingent

from Bradford the following Monday, and proceeded to attack the mills of the

Bradford district.

To add to the social unrest, indeed to foment it, there was the politics of

revolution, Chartism. "The People's Charter" sought to obtain many of the

rights which today we take for granted, often forgetting that they were hard

won. It demanded the following reforms:-

1. THE VOTE for every man over 21 years of age. (Votes for women weren't

thought of in those days!)

2. A SECRET BALLOT. (Elections in the early 19th century often involved

intimidation and violence.)

3. NO PROPERTY QUALIFICATION. (Opening Parliament to the common

man.)

4. PAYMENT OF MEMBERS. (As above.)

5. PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION. (The 1832 Bill had improved

things but fell far short of what needed to be done.)

6. ANNUAL PARLIAMENTS. (This has still not been achieved.)

These demands might sound reasonable to us today, but they did not seem so to

the ruling classes of the early 19th century. Such ideas were regarded as subversive,

and were treated accordingly. Chartism

and the Plug Riots were inextricably intertwined, and so were the political aims

and interests of those intent on quelling such "lawless and seditious" activities.

This is not to say, however, that Chartism was made up entirely of persons from

the lower classes. Chartism indeed enjoyed the support of many prominent men,

the Fieldens included.

It is quite possible that John Fielden would have attended the large Chartist

meeting which was held here at the Basin Stone in the August of 1842 (the same

month as the Plug Riots). 1842 saw a long hot summer of strikes, agitation,

violence and unrest. The great Chartist leader, Feargus O'Connor had been

touring the north west, visiting such towns as Bacup, Colne and Burnley, where

workers were on short time and strikes were breaking out. His fiery oratory stirred

up the feelings of the poor operatives of Lancashire (indeed he described himself as

the champion of the "unshorn chins, the blistered hands and fustian jackets"), and

it is hardly surprising that he was eventually arrested and charged at Lancaster in

1843 with inciting the people of Lancashire to riot.

An extract from one of O'Connor's speeches culled from the Halifax Guardian (8th

October 1836) will perhaps give you an idea of the kind of oratory to which the

ragged, motley crowd of locals, who assembled here at the Basin Stone to hear him

speak, must have been subjected:

"You think you pay nothing? Why, it is you who pay all! It is you who pay six to

eight million of taxes for keeping up the army, for what?? For keeping up the

taxes!!"

It seems incredible when one tries to imagine the crowd of over a thousand

people, which, in August 1842 gathered in this bleak spot to hear the speeches of

Chartist leaders. One of the speakers, Robert Brooke, a lame schoolmaster, urged

that men should cease working until the Charter was obtained, and that overseers

should be asked for relief and some other means be adopted to obtain it. For this

speech Brooke was arrested and tried at Lancaster with more than fifty other

Chartists charged with uttering seditious speeches. All, however, were acquitted.

Such repression as this did not, however, stop these political rallies. A meeting was

held, for example, at Pike Holes near Stoodley Pike, attended by nearly two

thousand persons to protest against the non-representation of working men in

Parliament, and the sum of l pound 13s 6d collected, to "help to freedom" Ernest

Jones, who in 1847 was to stand as M.P. for Halifax under the Chartist banner.

Meetings were frequently held by torchlight in these wild and remote places, and

the sight of a line of torches proceeding over dark and lonely moors must have

presented a strange, half pagan sight to those who witnessed it. One section of

the Chartists proposed the use of "Physical Force" ... one of the Chartists'

slogans proclaimed "sell thy garment and buy a sword" ... and it is said that men

secretly collected pikes and engaged in drill exercises on these remote Pennine uplands.

Unfortunately the 'Revolution' never came; but if Chartism itself declined,

Chartist ideas and principles certainly did not, and were to play a vital role in the

evolution of democracy in Britain in later years. John Fielden and his offspring "sold

garments" yet declined to "take up the sword", preferring to use the pen and the

spoken word in pursuit of their radical aims. The Fieldens were not, however,

totally averse to the use of political violence, as we will see further along the Fielden

Trail.

From the Basin Stone the path continues up the moor to Gaddings Reservoirs, a

popular local resort in summer and looking across the valley, up the gorge towards

Cornholme, Pendle Hill can be seen on the far horizon.

Gaddings.

There are two reservoirs here, Easterly and Westerly Gaddings. The latter is the

only one still containing any water, Easterly Gaddings having dried up and grown

over long ago. These were the final supply reservoirs to be built for the Rochdale

Canal, being the last of an immense complex of reservoirs and feeder channels

that stretched across the moors all the way from Blackstone Edge.

Water supply had always been a problem for the Rochdale Canal, as we have

already seen; and after the opening of the Manchester section of the canal the

problem became even more acute. In the years leading up to 1827 a complex

system of reservoirs and channels had been constructed. Altogether there were

eight reservoirs. The original reservoir for the canal had been the one at

Blackstone Edge, which under certain conditions washes over the moor road

leading down to Cragg Vale. Afterwards came White Holme, Warland

and Lighthazzles Reservoirs, Upper and Lower Chelburn Reservoirs,

Hollingworth Lake and finally the twin reservoirs here at Gaddings, begun in 1824.

In order to avoid the continuing "annoyance and torment" suffered by mill owners

in the Calder Valley, the canal owners agreed to build Easterly Gaddings for the sole

use of the mills, to be filled once a year from the feeders on Langfield Common.

Subsequently, the mill owners themselves (led by the Fieldens) reciprocated

by building Westerly Gaddings alongside. This was to provide additional capacity

and be a means of ensuring supply to the canal in dry periods. The supply from

Gaddings ran into Lumbutts Clough, and then to the Calder, passing through the

dams, goits and wheels of an assortment of mills en route, many of them (Lumbutts

for example) being part of the Fielden 'Empire' of outlying spinning mills. The

Fieldens, who led the mill owners' group, had a major interest in the maintaining of

water supplies in the Calder Valley, and Gaddings represents a compromise

drawn up between two previously warring interests.

From the 'beach' at Gaddings follow the drain towards the head of Black Clough.

Across the moor ahead can be seen the embankment of the Warland Reservoir and

drain, carrying the Pennine Way. If you happen to be here "in season" you will

see it alive with distant walkers, and here, on this defunct and overgrown

channel, snaking around the head of Black Clough, you will feel isolated and apart

from them.

Before reaching the head of Black Clough, near a point where the embankment of

the Gaddings drain has collapsed, turn left, following

a faint path down to the stream. From the stream ascend to the cairn on

Jeremy Hill, (a small knoll with a rash of stones nearby). From here pass over open

moor to the summit outcrop on Coldwell Hill, recrossing the by now totally

overgrown Gaddings Drain en route. Ahead can be seen Withens Clough

Reservoir and the wooded hillsides above Cragg Vale. On the right, the Pennine Way

approaches from the Warland Drain, a badly eroded path following a line of stakes over

the moor. (This is now paved, 2009.) On joining the Pennine Way, bear left, to Withens Gate. Just follow

the trail of bottles, coke cans and empty crisp packets!

At Withens Gate the Pennine Way continues onwards to Stoodley Pike

Monument. My route, however, recommends a short detour from the main route in

order to see the 'Te Deum Stone'. At Withens

gate, turn right along the causey, following the Calderdale Way towards Cragg

Vale. Soon the route reaches a large gate in an intake wall. Climb over the stile

here to find the 'Te Deum' stone on the of her side of the wall.

Although the 'Te Deum' stone has no particular association with the Fieldens it is

well worth the short diversion involved in order to see it. One face of this squat,

ancient stone is inscribed with the letters T.D. and a cross, whilst on the adjacent face is

the inscription 'TE DEUM LAUDAMUS'... "We praise thee 0 Lord!". Here,

at this , consecrated stone, weary travellers gave thanks and prayed for a safe

journey. Also, as with the traditional 'Lych Gate', coffins were rested here on their

way to burial in Heptonstall Churchyard, and no doubt prayers offered for the soul of

the deceased. In those days Heptonstall was the only church in the area, and here,

as in other parts of the Dales, it was by no means unusual for people to carry their

dead over them moors for burial. Many so-called 'Corpse Roads' owe their origins to

this necessary and time honoured practice.

From the 'Te Deum Stone' climb back over the stile, and bear right over moorland

towards quarry delfs. Beyond the quarried area the Pennine Way is rejoined.

From here it is simple (but stony) stroll Aong the well defined path which leads

to Stoodley Pike Monument (which is one of those places that never seems to get any

nearer!).

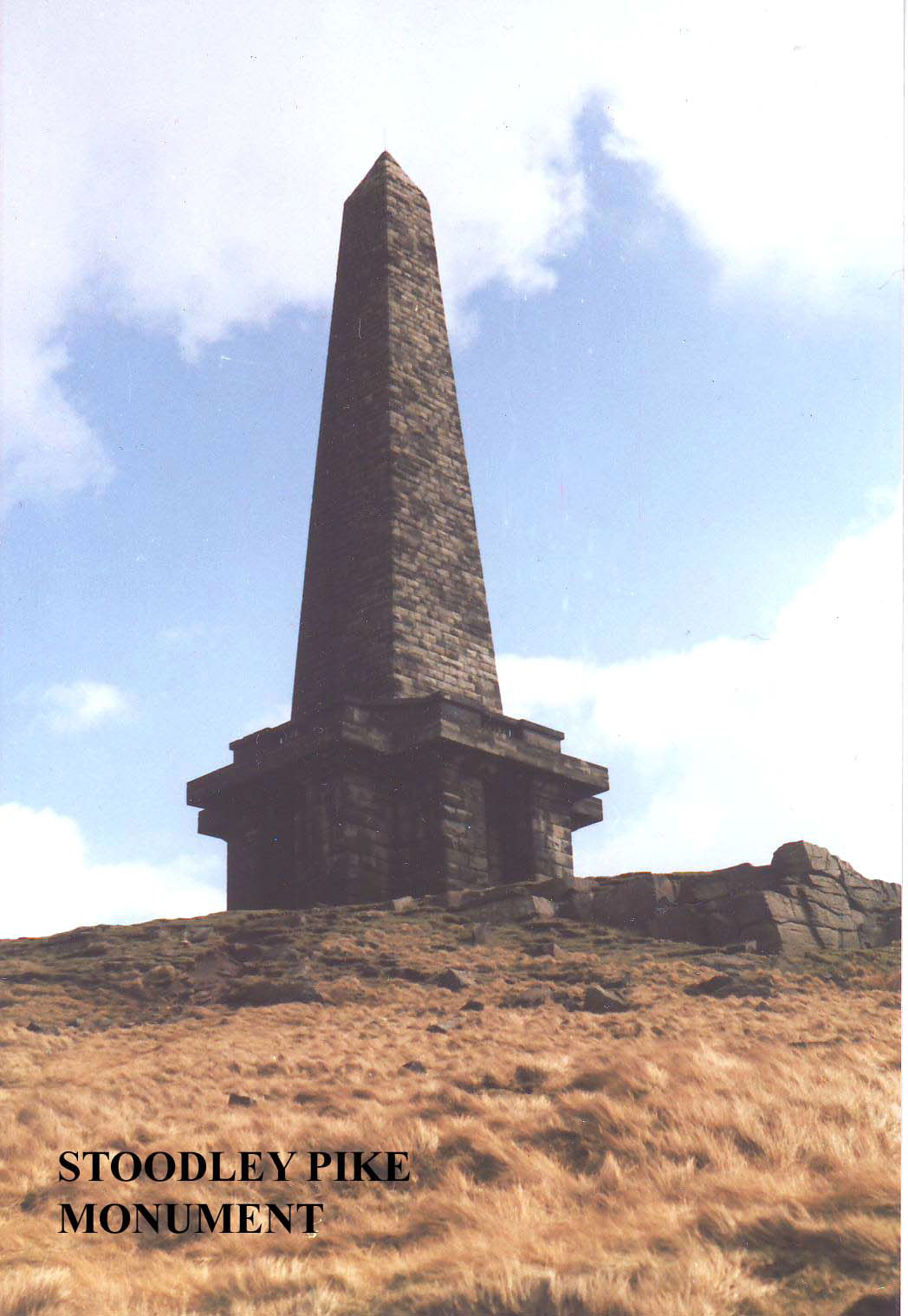

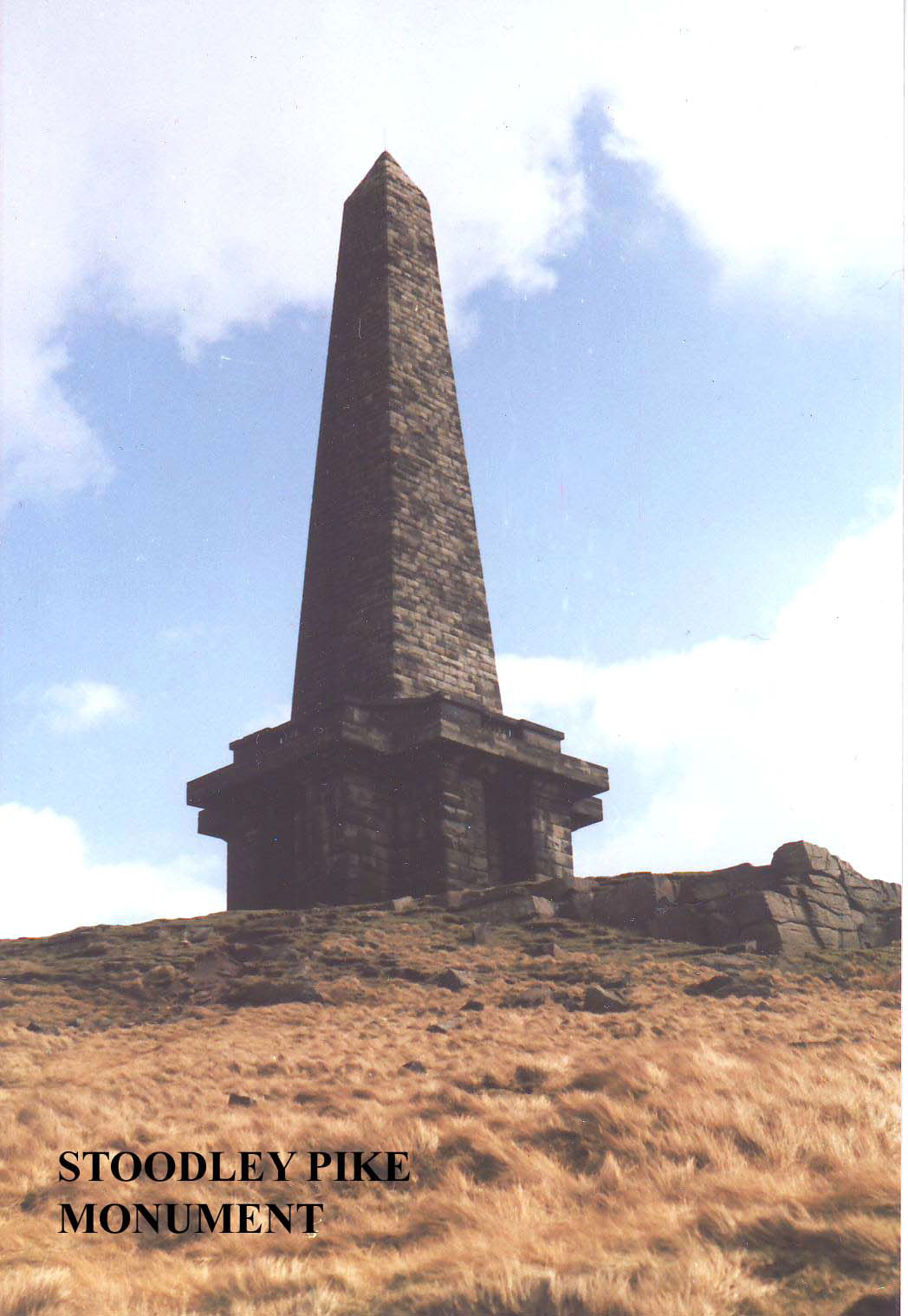

Stoodley Pike Monument.

Stoodley Pike Monument, standing at 1310 feet above sea level is the highest point

reached by the Fielden Trail. It is also the coldest, bleakest and wildest point! The Pike

appears to be welcoming, yet when you get there you soon find that it offers little in the

way of shelter from the elements. After groping your way through pitch darkness up

the staircase to reach the viewing platform, you find that it's actually colder in the Pike than it

was at ground level, where you at least had stone buttresses to break the wind. On a wet, cold

and windy day, with grey clouds billowing over the moors, Stoodley Pike can be a miserable

place indeed.

Stoodley Pike has been in existence much longer than the rather lugubrious egyptian

monument that crowns it. In 1274 Stoodley was mentioned in the Wakefield Manor Court

Rolls, and it seems fairly certain that originally a large cairn stood on the Pike,

probably covering an ancient burial, for tradition asserts that a skeleton was found on the

spot when the first Monument was constructed in 1814.

The first Stoodley Pike Monument was constructed by public subscription to

commemorate the surrender of Paris to the Allies in March 1814. Among the names

associated with its construction we find Greenwoods, Halsteads, Lacys, Inghams and, of

course, Fieldens. The foundation stone was laid with Masonic honours and a feast and

celebration held. The completed Monument was 37 yds. 2 ft. 4 in. high. For the first 5

yards it was square, above which height the structure was circular, tapering to the top.

Inside, a staircase of around 150 precarious steps led to the top where there was a small room

with a fireplace. While work was continuing on the monument, Napoleon escaped from Elba

and finally met his 'Waterloo', and it was in that year, 1815, that the monument was finally

completed.

Its career was ill starred. Within a few years it had suffered vandalism, and the

entrance had been walled up. Nemesis arrived on February 8th 1854 when, during the

afternoon, after a rumbling which startled the entire neighbourhood, it was discovered that

the Monument had collapsed. By an unhappy coincidence this happened on the same

afternoon that the Russian Ambassador left London before the declaration of war with

Russia. As a result of this, Stoodley Pike Monument has since been saddled with the myth

that its collapse heralds the approach of war.

On March 10th 1854 a meeting was held at the Golden Lion in Todmorden with John Fielden

in the chair. Object, to rebuild the Monument. John's brother, Samuel Fielden, was

also among the speakers at the meeting. It was estimated that the rebuilding would cost

between 300 and 400 pounds. On March 30th another meeting was held and it was decided, on

the motion of Samuel Fielden, that the Monument should take its present obelisk form. The

Fieldens, Sam, John and Joshua, contributed to the project along with other local worthies,

and 300 pounds was raised. On June 1st they held another meeting, at which designs were

submitted for the new Monument, resulting in the acceptance of the design of local architect

Mr. James Green of Portsmouth, Todmorden. A Committee of Works was appointed:

Chairman. John Fielden of Dobroyd.

Treasurer. Samuel Fielden of Centre Vale.

J. Ingham, Joshua Fielden of Stansfield Hall, John Eastwood,

Edward Lord, John Veevers, Wm. Greenwood of Stones, J. Green (architect), John Lacy and

Mr. Knowles of Lumb (secretary).

By now 600 pounds had been raised, helped by subscriptions from Thomas Fielden of

Crumpsall, Manchester, and Mrs. James Fielden of Dobroyd. In the end the total

bill came to over 812 pounds with 212 pounds outstanding. This debt was generously liquidated by

(guess who!) Mr. Samuel Fielden of Centre Vale.

Thus it was that in 1856, the year of the Peace (Crimean War) the Monument was

reconstructed in its present form. Within a few years the fabric was in need of repair, and

when this work was carried out in 1889, again assisted by funding from John and Samuel

Fielden, improvements were made; among them more adequate lighting for the staircase

and a lightning conductor. Once again, costs exceeded estimates, and once again Fieldens

cleared the debt. The emblems and inscriptions over the entrance to the monument were

carved by Mr. Luke Fielden, and it is believed that John Fielden himself composed the

inscription. The lettering is not too easy to read these days, so I will save you the trouble:-

"STOODLEY PIKE

A PEACE MONUMENT

Erected by Public Subscription.

Commenced in 1814 to commemorate the Surrender of Paris to the Allies and finished

after the Battle of Waterloo when peace was established in 1815. By a strange co

incidence the Pike fell on the day the Russian Ambassador left London before the

declaration of war with Russia in 1854 and it was rebuilt when peace was proclaimed in

1856. Repaired and lightning conductor fixed 1889."

What of the Pike today? If you can find a pleasant enough day to visit this bleak spot,

the views are excellent, ranging from Holme Moss and Emley Moor to the south and

Boulsworth Hill and the Haworth moors to the north. Less far afield we can see right

into the heart of Todmorden and up the gorge towards Cornholme and Hartley

Royd. Immediately below, the main Burnley Road can be seen through a gap in the hills,

passing through the vicinity of Eastwood. It is incredible to think that it was somewhere down

there, near Callis Bridge, that James Shepherd rescued the little boy, Samuel S. Fielden, from

the raging river, after he had been swept there all the way from the centre of Todmorden.

No wonder the poor boy did not survive his ordeal!

Stoodley Pike Monument belongs to Todmorden, despite being perhaps nearer to

Hebden Bridge. The Pike is not visible from Hebden Bridge, whereas it dominates

Todmorden from a distance and can be seen from every part of the town. It is not for nothing

that the Monument is displayed in Todmorden's Coat-of-Arms. Yet it is not unique. The

strange compulsion that led 19th century Yorkshiremen and Lancashire folk to build

bizarre 'follies' on their hilltops is something of a mystery. A tradition was established

that in an odd, and more functional, kind of way has persisted into the 20th century with

the masts and towers of Holme Moss and Emley Moor, not to mention the host of smaller TV

booster transmitters to be found on hillsides all over the area. Yet the old 'follies'...

Wainhouse Tower, The Pecket Memorial, Rivington Pike, the Earl Crag Monuments

near Keighley, Wainman's Pinnacle and Lund's Tower, the Jubilee Tower on

Almondbury at Huddersfield .... all bear mute testimony to this strange urge.

Perhaps it is similar to the one which prompts lesser mortals to add stones to cairns on

the Pennine Way. Who knows?

It is time to move on. If you are feeling really energetic you can follow the

Pennine Way to Kirk Yetholm. If you are following the Fielden Trail, however,

you will ignore such temptations and head back towards Todmorden.

From the entrance to the Monument walk straight forwards towards the edge of

the scarp, bearing slightly left. Soon a path can be seen descending the steep face

of the hillside towards a cluster of hospital buildings on the 'shelf' below. This is

the Fielden Hospital, which was built at Leebottom in 1892 by John Ashton

Fielden, who was carrying out the wishes of his father, the late Mr. Samuel

Fielden of Centre Vale. Samuel had long displayed an interest in the welfare of

children and the building of a children's hospital had always been his dearest wish.

Near the end of the Fielden Trail at Centre Vale Park is the Fielden School of

Art. This was originally built and maintained as an elementary school at

Samuel's own private expense. His wife, Sarah Jane, was particularly notable in

this respect. She was the daughter of Joseph Brookes Yates of Liverpool, (Samuel

married her at Childwall Church near to that town in 1859), and no doubt she would

have been quite familiar with the conditions endured by the slum children of that

sleazy, bustling port. All this may be speculation, but even if she was not

influenced by such realities, her interest in the welfare of Todmorden's

children is in no doubt. In August 1874 the first School Board in the Todmorden

district was elected and Mrs. Fielden was its most distinguished and active member.

She devoted many years to the study of the education of younger children, at first

in unpretentious buildings in Cobden St., then later in her own school at Centre

Vale, where she engaged in education work along lines which she herself had

searched out and practically tested. (Centre Vale School continued until 1896).

But back to the Fielden Trail. The path from Stoodley Pike passes steeply down

to the left through Red Scar and after meandering down the moor eventually

reaches London Road near Higher Greave. Bear left, following this track to

Mankinholes.

Further down the hillside below London Road is yet another hospital,

Stansfield View. This was originally the Union Workhouse, although it wasn't

constructed until the 1870s (the original Poor Law Amendment Act having been

passed in 1834). The reason for the

delay was the fierce and often violent opposition to this despised institution, an

opposition in which the Fieldens were particularly vociferous and active. Events

in Mankinholes in 1838 were to have a particular impact on the area and delay the

implementation of the new Poor Law for many years.

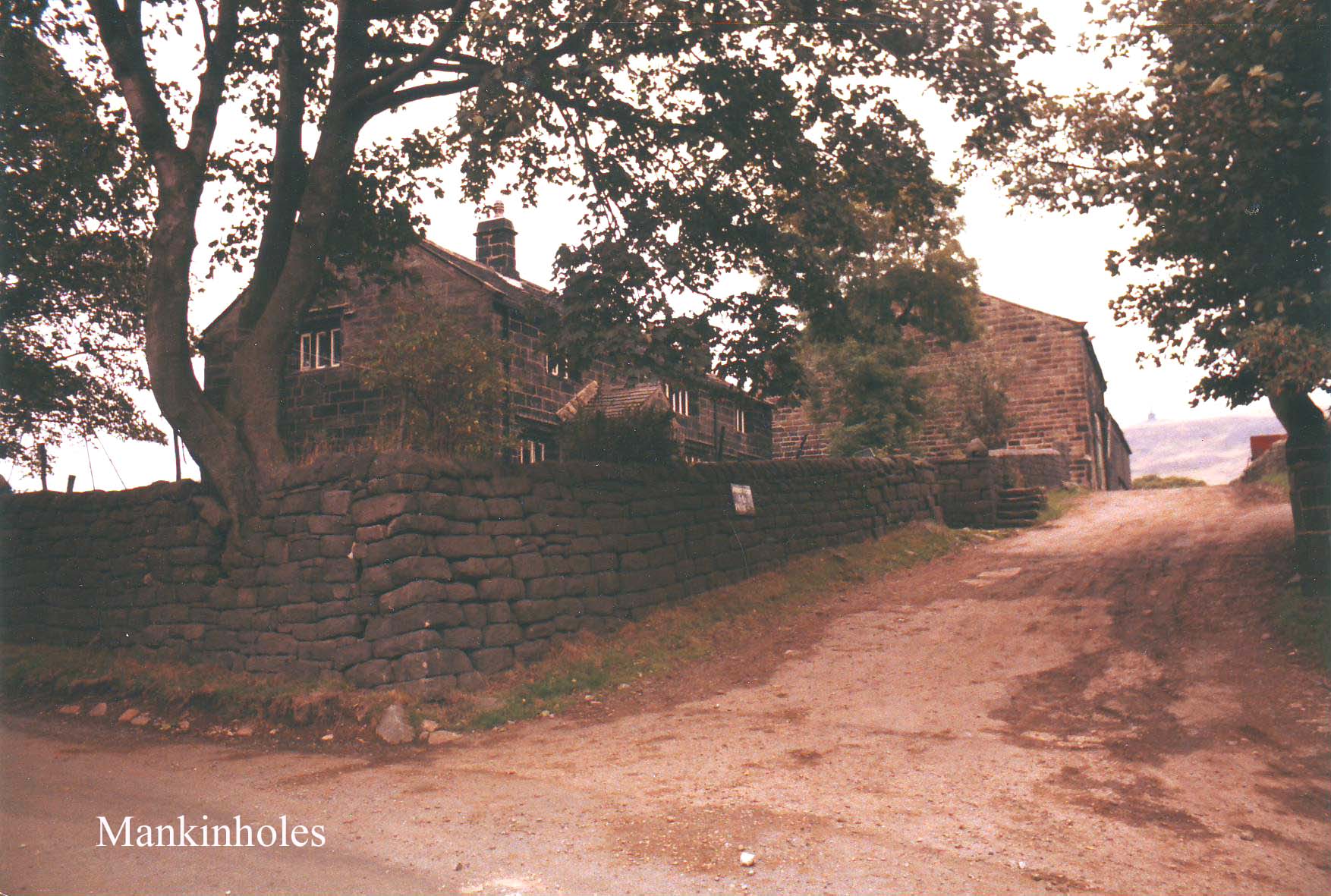

Descending slightly, the walled lane emerges on the metalled road leading to

Lumbutts at the southern end of Mankinholes village. Beyond Lumbutts this

road connects with the Salter Rake Gate we passed over earlier on the Fielden

Trail. At the end of London Road turn right into Mankinholes village. On the

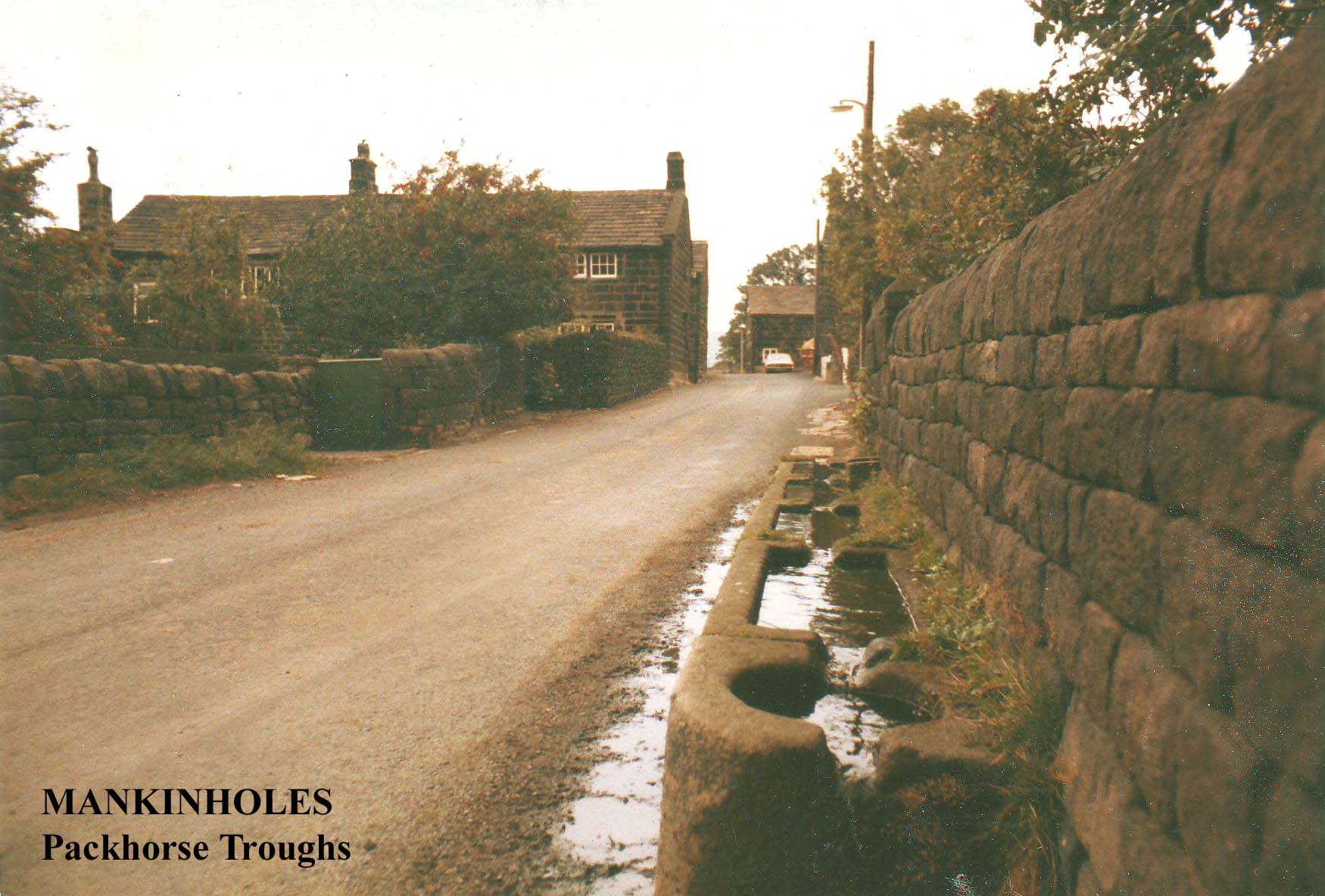

right is a beautifully designed stone trough which was constructed as a watering

place for the packhorse trains, which at one time were the almost universal

traffic of the area. It is hard to imagine that in the centuries prior to the Industrial

Revolution this sleepy little community lay astride what was then a busy trade route.

. . . IS DELIGHTFUL! Apart from the tarmac lane which brings the odd

speeding motorist through its meandering, tree shaded heart, Mankinholes is

venerable and peaceful, a community that time seems to have passed by. It is

tempting to call the place "pre industrial", but more accurate to call it "pre

Industrial Revolution", for although mills, canals, towns and railways have left

Mankinholes alone on the hillside with its memories, it was nevertheless, in the

days of its prosperity, almost entirely given over to the domestic textile industry.

Even with the Industrial Revolution, textiles did not die out up here, as the

traditional domestic woollen industry was simply replaced by Fielden's cotton

spinning mill at nearby Lumbutts, just a little further along the hillside. Up here on

the 'shelf of land just below Stoodley Pike we are given the rare opportunity of

seeing two small and different industrial communities side by side, the one

domestic and the other factory based, representing two different epochs in the

history of the area.

In Mankinholes we see the earlier epoch. A woollen industry characterised

by the spinning wheel and the handloom, the jingling packhorses and their

colourful drivers, the "broggers". When Defoe passed through this area in the

18th century, he remarked upon the 'pieces' of cloth which could be seen on every

hillside, stretched upon their tenter frames (the origin of the expression 'on tenter

hooks'). Weavers would often carry pieces to market on their backs as we have

seen. Besides the weavers there were the croppers with their enormous shears for

cutting the nap on the cloth; there were dyers, fullers with their stocks and

waterwheels, their tiny mills serving an industry centred on the hillfarmer's

hearth and home, yet pointing towards the new industrial age that was to come, for

in the end the 'hearth and home' would come to serve the mill and the flow of

progress would create new communities and environments, leaving the time

honoured industries of communities like Mankinholes high and dry.

So Mankinholes remains aloof and detached from the bustle below, nursing its

memories, a community put out to pasture. Mankinholes, like other places we

have encountered along the route, was a stronghold of early Quakerism, the first

recorded meetings in the area being held here at the house of Joshua Laycock, to

which a burial ground was attached on December 3rd 1667. Half a little croft called

'Tenter Croft' was rented as a burial ground at a yearly rent of 'one twopence of

silver' for a term of 900 years. This plot of ground still forms part of one of the

farms at the northern end of the village, and on one of the outbuildings is a

gravestone with the inscription "J.S. 1685". Within a short time of the passing of

the Toleration Act in 1689, Quaker Meeting Houses were registered in

Haworth, Mankinholes, Bottomley and Todmorden. Eventually, as the

development of the area began to centre on the valley below, the Quakers moved

nearer to Todmorden, to Shoebroad and ultimately to Cockpit Hill behind Fielden

Square in Todmorden.

With the end of the Quaker persecutions, Mankinholes returned to its tranquil life.

In the wake of the Quakers came the Methodists, who built a chapel here in 1815, and

in the same year a school was opened with Mr. William Bayes of Lumbutts as

headmaster. As the cotton spinning industry developed at nearby Lumbutts, the

traditional domestic industries of Mankinholes declined, and this little

community might simply have passed into oblivion and obscurity had it not been for

the sudden and extremely violent scenes which took place here on the afternoon of

Friday November 16th 1838, events which were to have a profound effect on the

neighbourhood for some years to come.

These troubles were caused by the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which

abolished the old system of parish relief for the poor which dated back to the

time of Elizabeth I, and brought in a new regime, administered by three

commissioners who rapidly became known as the 'Three Bashaws (Pashas) of

Somerset House'. These commissioners were empowered to group parishes into Unions

where workhouses (which came to be called Unions) would be established.

As a result of this, the able-bodied might receive no relief except within the workhouse,

where conditions were deliberately made harsh. In the workhouse men and women were

kept apart to prevent childbearing, and to enter it meant leaving one's home and loved

ones to suffer perpetual imprisonment simply for having the misfortune to be poor or

unemployed.

In the south the new act was quickly implemented, but in the north it was resolutely and

often violently opposed. "The New Bastilles" as the workhouses were called, were set on

fire or pulled down; and in many northern towns it was many years before the act could

be enforced. To understand the reason for this violent opposition we must look more

closely at the objects and aims of the act, and at the social and economic differences between

the northern and southern regions.

The aim of the Poor Law Amendment Act was primarily to reduce vagrancy by making it

impossible for the poor to get an easy living by "scrounging" off the parish. In certain areas

this situation was indeed the case, with many people preferring to live on relief rather

than seek honest employment. It was reasoned that the introduction of this new system

would make living "on the Parish" so harsh, restrictive and unpleasant that a man would

take on any kind of work rather than submit himself to the horrors of the workhouse.

The implementation of the law proved that there had indeed been some point to the

argument. The numbers of people seeking relief dropped drastically in the south, but

unfortunately the government of the day completely misjudged the effects of the new Poor

Law upon the industrial north, where a completely different situation was to be found.

In the north things were different. Work was centred on the new factories and the factories

were having difficult times. Traditional industries like handloom weaving were in

decline, and in factories with the new machines fewer hands were needed to do the

work of many. Wages were poor and unemployment was widespread. Naturally

enough, the arrival of the workhouse upon the scene proved to be the last straw. In the south it

may have persuaded the 'idle poor' to seek work, but in the north there was often no work of

any kind to be had, especially in areas where the whole community was often entirely

dependent on a single industry, or even a single employer. People were forced to enter

the workhouse through no fault of their own and be separated from their loved ones with

no prospects save harsh labour and perpetual imprisonment. Furthermore, the

workhouse initiated a downward spiral, for if work was available, the poor, rather than submit

to the rigours of the workhouse and the workhouse test and lose their homes, would accept

lower wages and longer hours and thus aggravate still further the great struggle with poverty

in which so many of the weavers and workers were at that time engaged.

Lower wages and longer hours would, of course, benefit the mill masters, giving them

an endless supply of cheap labour, but thankfully there were those more enlightened souls

who were aware of the injustice of the new Poor Law, and who were ready to organise

local opposition to the hated workhouse.

In Yorkshire there were two hotbeds of Poor Law opposition, Huddersfield, led by Richard

Oastler, and the workers of Todmorden, led by 'Honest John' Fielden. On May 13th 1837

'Honest John' was speaker at a huge West Riding anti Poor Law rally held on Hartshead Moor

near Liversedge, and on 19th February 1838 he became vice chairman of Earl Stanhope's

Anti Poor Law Association. The struggle against the workhouse in Todmorden was

bitter. Elections of 18 Guardians for the seven townships in the Union were ordered

in January 1837, but Todmorden, Walsden and Langfield refused to proceed, and when

the Guardians did meet on 6th July 1838, their opponents forced them to adjourn. As

regards John Fielden's involvement in these events, his opposition was vigorous: "A most

extraordinary course of conduct was pursued by Messrs. Fielden & Co.," who dismissed

all their workers to overload the system and force the Guardians to resign. Unfortunately they

"wholly failed in this remarkable endeavour to intimidate the Guardians" and re opened

their works within days, on the 16th. John then warned the Guardians with an ominous

placard:

"To oppose force we are not yet prepared, but if the people of this and surrounding districts

are to be driven to the alternative of either doing so, or surrendering their local government

into the hands of an unconstitutional board of lawmakers, the time may not be far distant

when the experiment may be tried, and I would warn those who provoke the people to such a

combat of the danger they are incurring."

The warning was duly noted and the Guardians were at first cautious, not attempting to

implement the Act fully for some time. But attempts to levy rates through the Todmorden and

Langfield Overseers led to tangled legal actions, and when two Constables were sent from

Halifax to Mankinholes to seize the household goods of Mr. William Ingham, the Overseer,

for his refusal on behalf of the township of Langfield to pay the new Poor Law levy, they

could not have been aware of the seething cauldron of violent resentment that they

were about to overturn.

What happened next is best expressed in the words of the time, from a pamphlet account

published in 1838:-

"The Overseer of Todmorden, Mr. Ingham, has recently had a fine imposed upon him for

neglecting to pay the demands made upon him under the new [Poor] Law. In consequence

a distress warrant was taken out against him on 8th December Thursday. Feather, the Under

Deputy and King, Sergeant of the Watch, proceeded to Langfield to mark the goods and

give the usual notice that if the fine was not paid the goods would be taken and sold ... On

Friday 16th May they went, taking with them a horse and a cart ... Immediately upon the

Officers being seen, a woman, who was standing with several others upon a piece of rising

ground at a short distance called out. "Ring the 'larum bell", she repeated, and forthwith a bell

commenced ringing ... with tremendous violence. In almost an instant the bell of Mr.

Fielden's factory situated at Lumbutts about two fields length from Ingham's house was

set a ringing and was followed by several others. These bells were rung from 10 to 15

minutes incessantly.

The game was now commenced, factories emptied of men armed with clubs, etc.,

hastening to the scene of action. Soon there was a mob of two thousand people gathered!"

The mob threatened to raze his house if Ingham would not deliver up the Constables,

who, after having been mauled by the mob, were now hiding in Ingham's house.

Eventually, however, an agreement was reached whereby the Officers agreed to take an

oath that they would not return here again on such an errand. The mob was now slightly

pacified, but not content with this they demanded that the Constables should apologise

on their knees. Neither Officer was willing to submit to this kind of degradation, so when

Ingham finally opened the door "both Officers were seized in an instant and the mob

commenced stripping them of their clothes. Feather, now seeing the position they were in,

begged for mercy. The mob shouted: 'we will spare your lives! Mr. Fielden told us to spare

your lives!'

Left now to the mercies of the mob the Officers were "most severely kicked, thrown upon

the ground, dragged by their heels upon the ground and suffered the most murderous

treatment. Their hats were taken off, filled with mud, and then with great violence forced

over their faces. Thus blinded and choked they continued to make their way towards

Stoodley Bridge." Half a dozen of the mob protected them for a time, but, being attacked

by the remainder, they left them to their fate.

Upon arriving at the last turn in Stoodley Plantation the mob threatened to throw

them into the canal: "One man who was holding King's left arm said 'Now if you will

make a split [run] I will give you a chance!' [They were about forty yards away from the

canal]. He [King] did so but was immediately pursued by the man who had hold of his right

arm. This fellow, who King says was one of Mr. Fielden's mechanics, proved to be a

treacherous rogue who tried to pitch him into the cut . . ." The Officers eventually

found refuge at a Mr. Oliver's, and managed to get some clothes and catch

the 'Perseverance' Mail Coach back to Halifax (their cart having been smashed and burned

and the horse turned loose by the mob).

That might have been an end to it, but on the following Wednesday, (21st November), a

rumour spread to the effect that the Constables were returning once more, this time

with a body of soldiers. The balloon went up and the mob gathered; but the

rumour turned out to be a damp squib. Not to be thwarted however:

"The infuriated mob determined to manifest their indignation at the new Poor Law

and its advocates in the following summary manner...From Mankinholes they

proceeded to Mutterhole, the residence of Mr. Royston Oliver, one of the Poor

Law Guardians, and broke the whole of his windows and doors; after which they

proceeded to Wood Mill, breaking the windows of Mr. Samuel Oliver's house, and

the windows of the inn where the Guardians hold their meetings."

From here the mob went "then to Stones Wood, the residence of Messrs.

Ormerod Bros., destroying windows, doors and furniture, and on their return called

on Mr. Helliwell of Friths Mill." The mob then went to Wattey Place (Wm.

Greenwood), Jeremiah Oliver (the surgeon) and the house of Miss Holt, the

draper, whose windows were smashed. Also suffering damage were the houses

of Mr. Henry Atkinson (shoemaker) and Mr. Stansfield, Solicitor and Clerk to the

Board of Guardians.

On reaching Todmorden Hall, which was at this time the residence of James

Taylor Esq, the Magistrate, they destroyed windows, doors, furniture, family

paintings and carriages, and carried off spirits, wines and the contents of the cellar.

Next they went to the house of Mr. James Suthers, who lived up Blind Lane and

who was the Collecting Overseer under the new Poor Law for the Todmorden

District. Here again, windows were smashed and the house plundered, and the mob

would have made a bonfire of the furniture but for the appeal of a lady nearby who

feared for the houses catching fire; so instead they threw it into the nearby

watercourse. The mob ended its rampage at the residence of Mr. Greenwood

at Hare Hill, where, after breaking windows and doors they set the house on

fire, which was quickly extinguished by a fire engine sent from Fielden's Mill at

Waterside before much damage was done. All the people whose houses were

attacked were either Union officials or "other persons supposed to be friendly to

the Law"; Miss Holt for example, whose windows disappeared under the

vengeance of the mob, was sister in law to Joshua Fielden, but had shown

herself by chatter over her shop counter to be in favour of the new Poor Law.

Retribution was swift. Soldiers were brought in and large numbers of Fielden's

workers were arrested by police and troops. Of 40 men tried however, only one

was actually imprisoned. The Fieldens and their workers had won ... it was not

until 1877 that Todmorden finally agreed to build a workhouse.

After these events Mankinholes reverted back to its former tranquility

(although it must have seen a little activity four years later with the Chartist and

Anti Corn Law disturbances). Mr. Ingham's house still remains, standing in a

cluster of trees in Mankinholes with its gable to the road. It seems hard to

imagine the scenes that took place here on that fateful Friday afternoon in

1838. Such violence seems somehow incongruous in this gentle place.

But back to the present. From Mankinholes the Fielden Trail follows the

route of the Calderdale Way into Todmorden, via Lumbutts. Just beyond the

northern end of the village the Wesleyan Methodist Sunday School appears on

the right. This was built by public subscription in 1833. The adjoining ground

was the site of Mankinholes Methodist Church, and a sign by the gate informs

us that it was "built in 1814, enlarged in 1870, rebuilt in 1911 and closed in 1979."

Opposite the chapel gate a paved track leads between walls to the Dog and

Partridge or Top Brink Inn at Lumbutts, one of the oldest hostelries in the

district. Sheep fairs were once held here, and business deals clinched over a

pint of ale. The Langfield Moor Gateholders met here and the pub was a

traditional haunt of the 'Broggers' (the packhorse men).

Before reaching the front of the Top Brink, a cobbled ginnel leads down to the

Lumbutts Road near the water tower. Turn right here: soon a stream passes

beneath the road and an imposing mill house appears on the left in front of the

water tower. This house, and the tower, is all that remains of Fielden's Spinning

Mill. Around this mill in the 19th century mushroomed the cotton

manufacturing community of Lumbutts.

Lumbutts.

Sited on the fast flowing stream flowing down Black Clough from Langfield

Common, Lumbutts was the ideal site for the development of a small

manufacturing community of the Industrial Revolution. Whereas Mankinholes

owed its livelihood to farming and to the domestic based textiles of an earlier

age, Lumbutts, in contrast, was almost entirely created by, and centred around, its

cotton mill; which was one of the many remote outposts of the Fielden's

cotton manufacturing 'empire'. Nearly all of its 200 or so inhabitants were

employed by Fieldens in the 19th century.

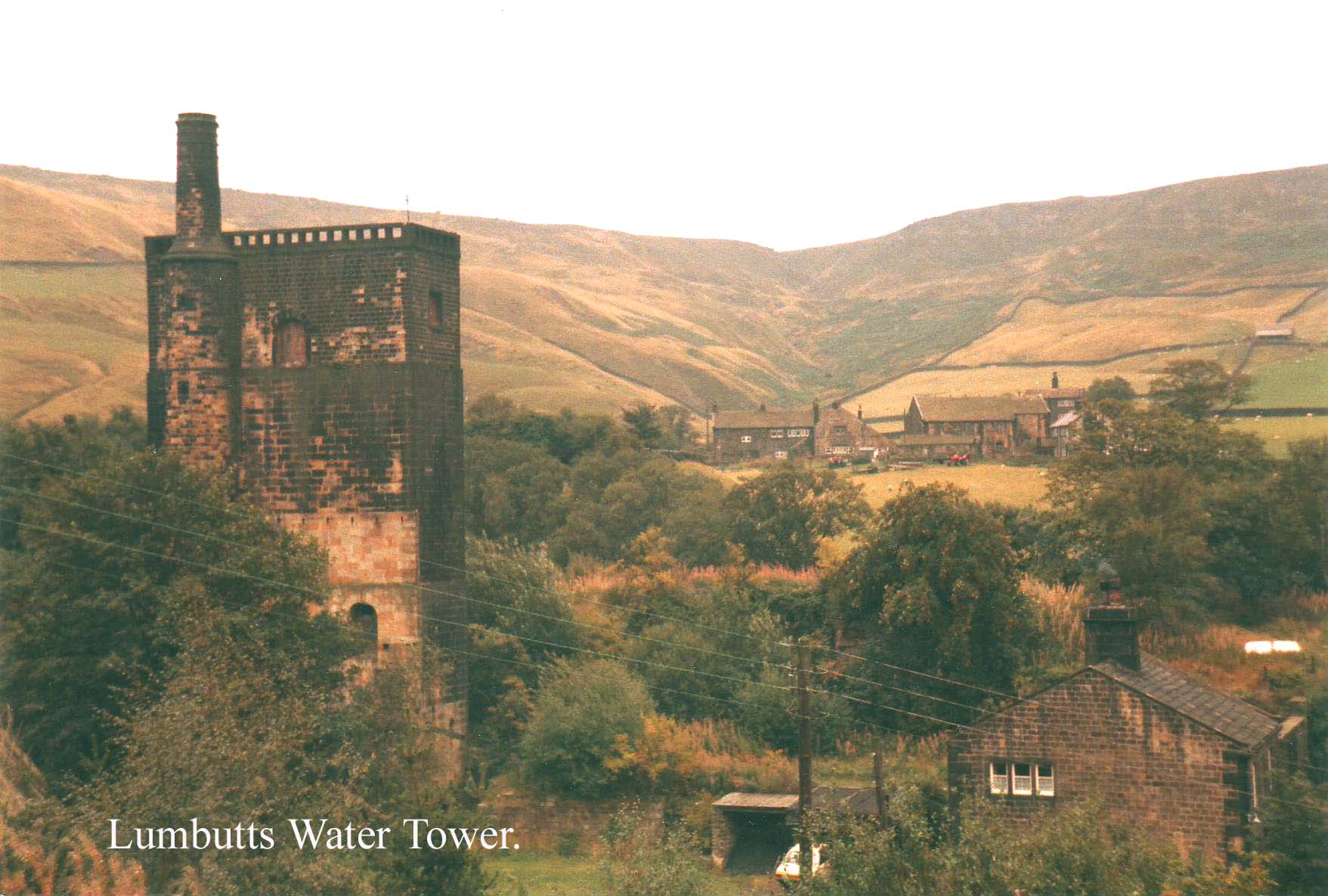

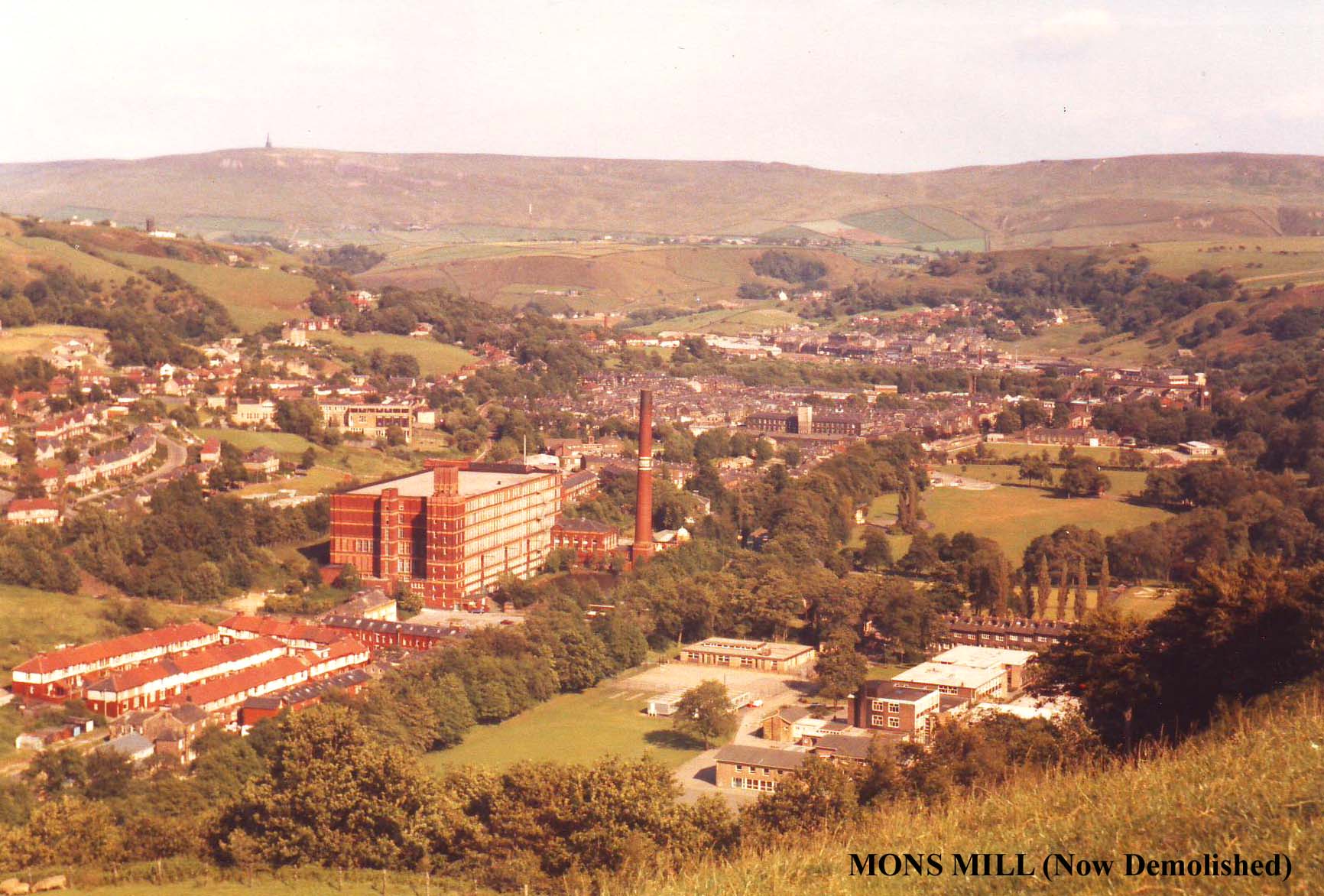

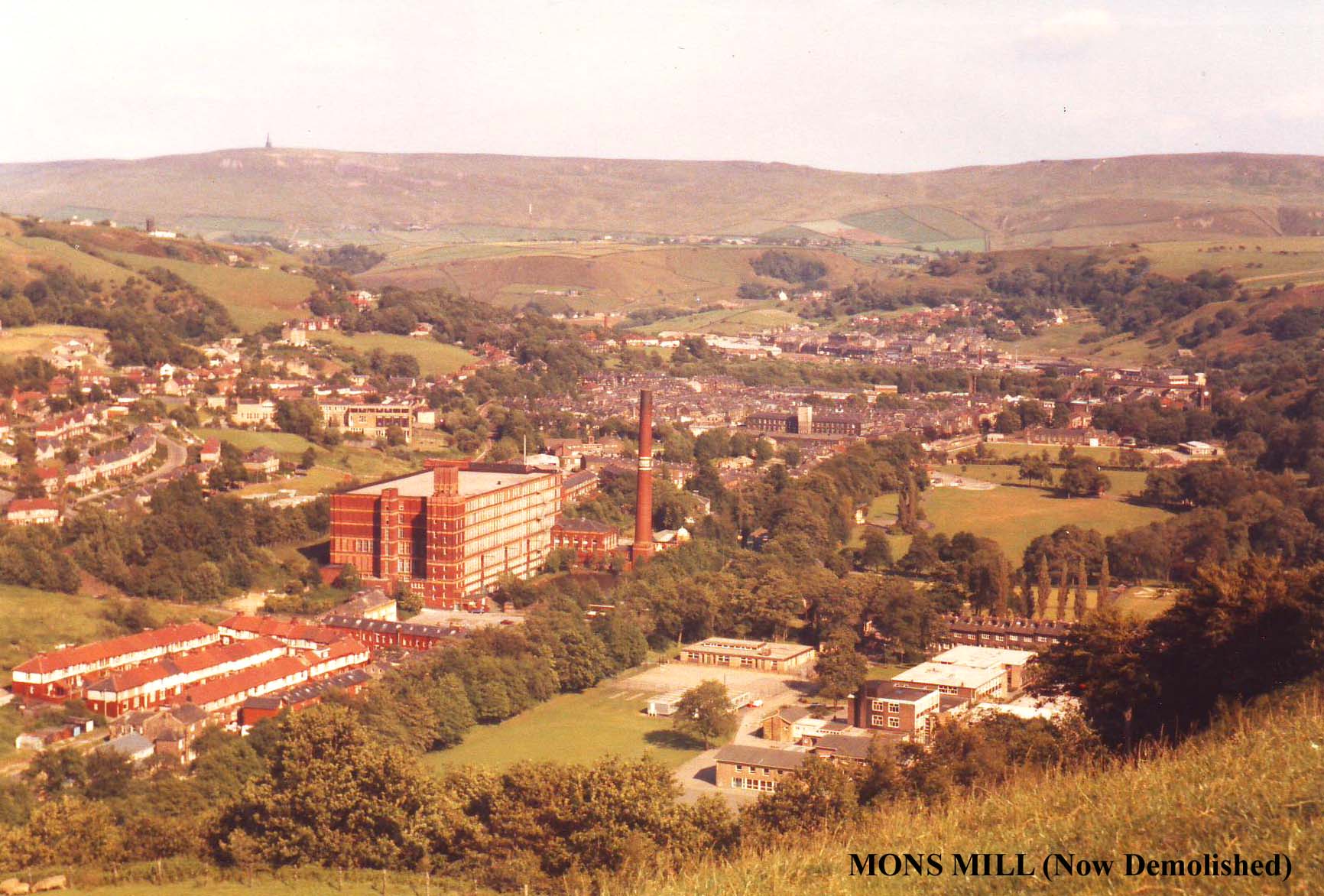

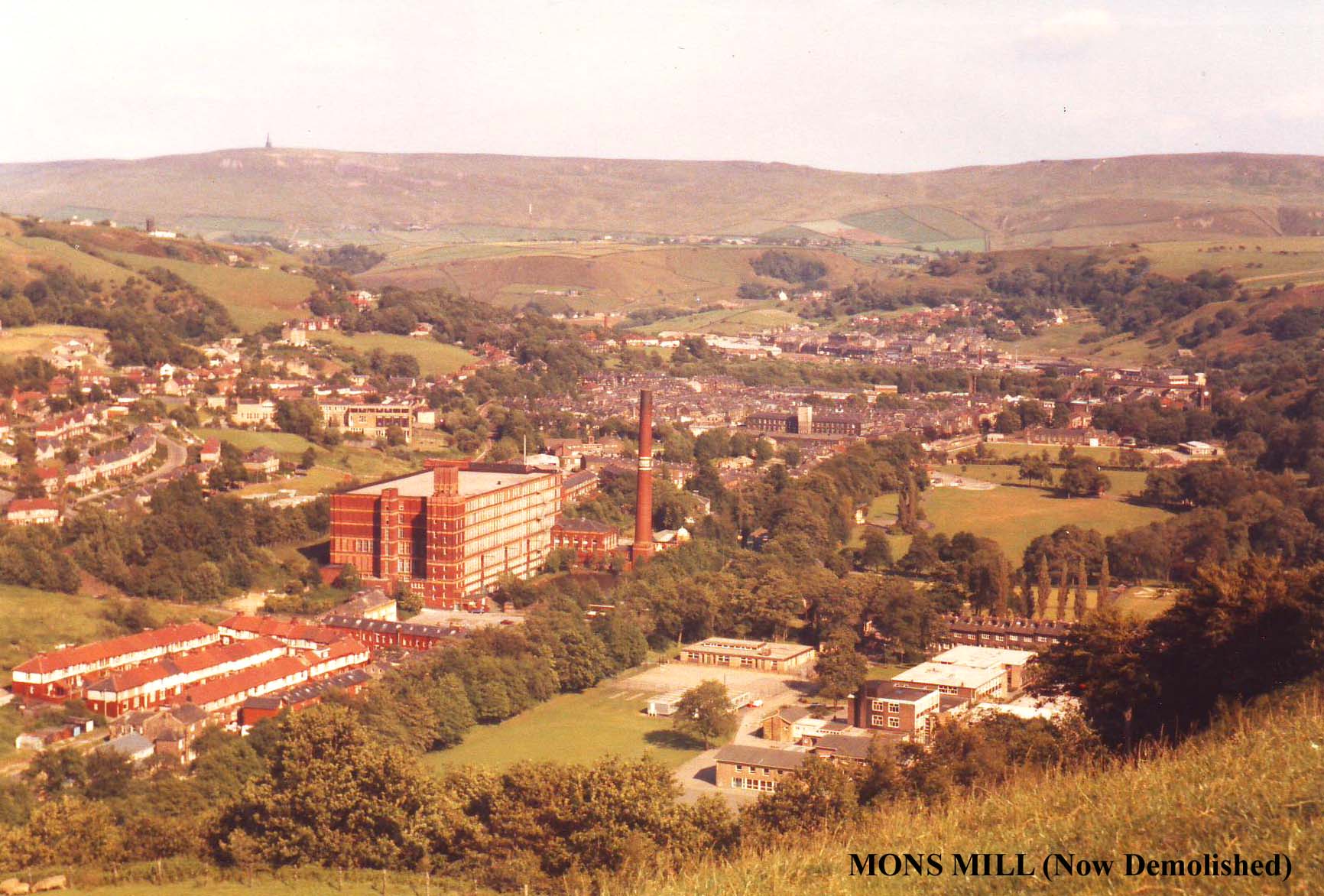

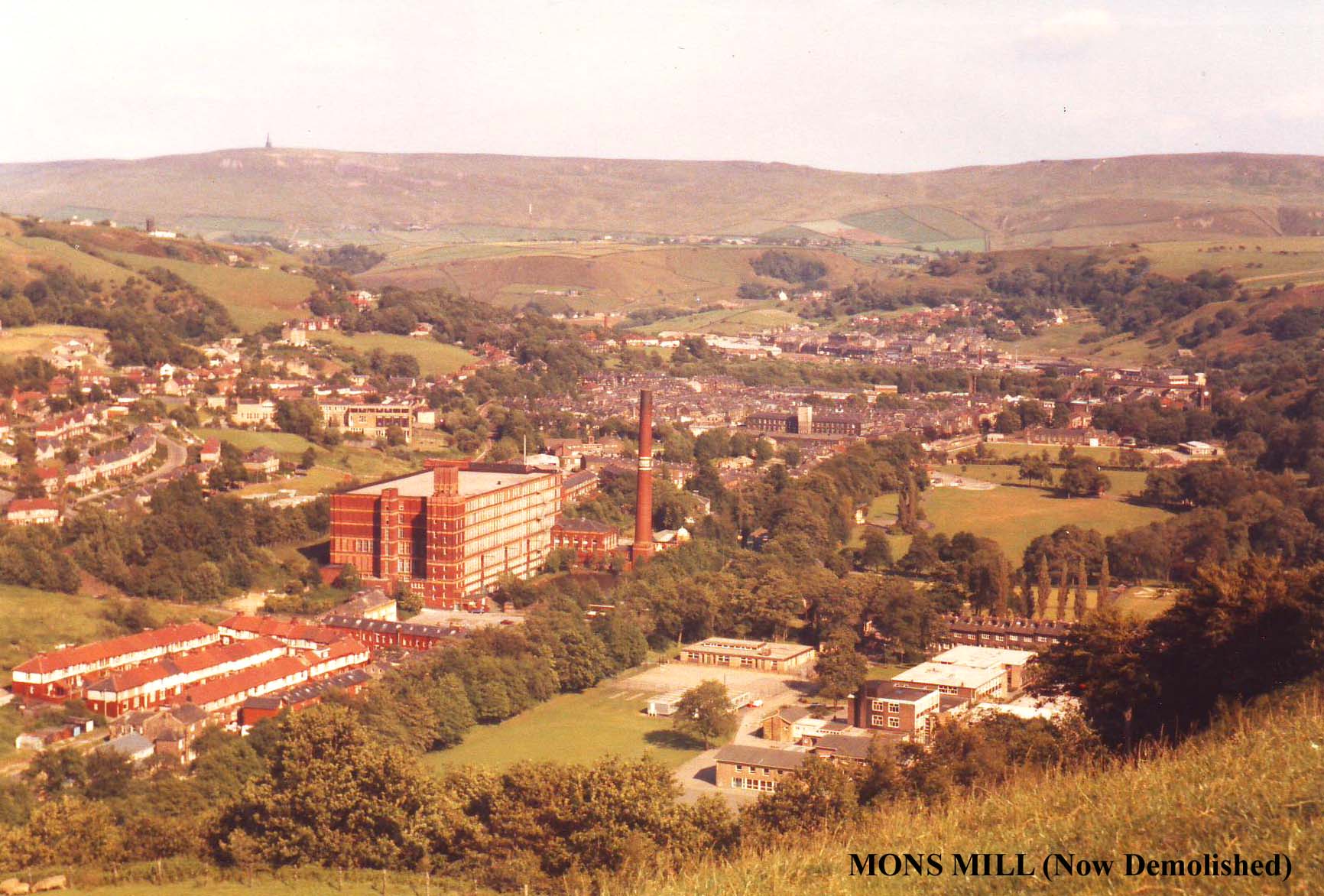

The mill that stood in front of the huge tower was (on the authority of a local retired

postman I conversed with) Fielden's Scutching and Carding Department. On the other

side of the road stood the Spinning Shed. Today only the water tower, the dams that

fed it, the manager's house, and some workers' cottages remain to testify to the substantial

manufacturing establishment that developed here. The water tower especially was

a fine work of engineering. In its day it housed three overshot waterwheels which

were fed from the dams up Black Clough. The three wheels were arranged in a

vertical sequence so that each wheel had its own feed, but was also driven by the

water falling from the wheel above it. The top water fell a total distance of 90 feet

and the whole system was capable of generating 54 horse power. Today, though

ruined, the tower is still a fascinating structure and is a landmark visible from all

the surrounding moorland edges.

From Lumbutts follow the metalled road onwards towards the Shepherd's

Rest. On this tarmac road we are, in fact, walking along part of the Salter Rake

Gate. A little further along, near the pub, the old stone causey coming down

from the moors joins up with the modern road, where it disappears beneath the

tarmac. The Fielden Trail however, leaves the road before reaching this point.

After passing 'Causey West' on the right, turn right by pole no. 215 at Croft Gate

to Croft Farm. Just beyond Croft Farm pass through a stile and follow the

footpath to Far Longfield Farm. (Look for the Calderdale Way waymarks). The

Shepherd's Rest and the road can be seen across fields on the left.

At Far Longfield, go through a stile by pole no. 273, following the path through

Longfield Stables to a farm road beyond which llamas may sometimes be seen

grazing. (Yes, I did say llamas!). On reaching a junction of farm roads a small dam

appears in the field opposite. Turn right, following a walled lane. to:-

Shoebroad Quaker Burial Ground.

If you wish to explore this place more closely it will be necessary for you to shin

over the wall, as the entrance gate was walled up long ago. The exercise is hardly

worth the effort, however, as apart from a few gravestones belonging to the Oddy

family, there is really nothing there to see. This is a Quaker Burial Ground, and

Quakers were not allowed headstones or grave monuments until relatively recent

times, the tradition being one of anonymous burial in an unmarked plot of

ground. It might come as rather a surprise therefore, when I tell you that there are

at least 24 Quaker Fieldens buried in this tiny plot of ground, and goodness

knows how many other people from other Quaker families in the district. Here

lie the mortal remains of Joshua Fielden (I) of Bottomley, who along with his

brother John Fielden of Hartley Royd, were amongst the first people in the district

to become Quakers. He was buried here on 21st April 1693, and was followed by

successive Joshuas, the last Joshua being 'Honest John's' father, the enterprising

Joshua Fielden (IV) of Edge End and later Waterside, who was buried here in

April 1811. The last Fielden to be buried here was old Joshua's youngest surviving

daughter, Salley Fielden, who died at Waterside on 18th September 1859 aged 79.

(She was Mary Fielden's aunt.) Also buried here are John and Tamar Fielden

of Todmorden Hall, whom we will shortly encounter on the last lap of the Fielden

Trail.

From the Quaker cemetery the track continues to descend towards Todmorden,

passing Shoebroad Farm (another Quaker meeting place) on the left. On reaching the

bend at Honey Hole, do not follow it, but instead continue onwards through an iron

gate which leads into the cemetery. The gravel path turns left, descends through

trees and shrubbery and finally emerges at the chancel end of Todmorden

Unitarian Church. On the left, at the corner of the church, are the graves of

Samuel and Joshua Fielden, two of the three brothers who left such a lasting mark

on the architectural character of Todmorden. (The third brother, John Fielden J.P.

of Dobroyd Castle, is buried at Grimston Park near Leeds.) Also buried here is

Samuel Fielden's wife, Sarah Jane, whose educational works were recently

discussed. The inscription tells us that she was born at West Dingle, Liverpool,

on 5th November 1819 and died at Centre Vale in 1910. There is less inscription

on Joshua's grave, although we note with some surprise that Joshua, by a strange

twist of fate, died on his 70th birthday, being born on March 8th 1827 and dying on

the same date in 1897. My first visit here seemed a rather haunting experience.

There I stood, with one of Samuel Fielden's letters in my pocket, along with

correspondence written by his sister Mary. It was strange to reflect that had fate not

brought this material into my possession, I would not even have been aware of his

existence, still less visited his grave. It was equally strange to think that his

birthday was the same as my own, 21st January. For me, my own personal Fielden

Trail began right here.

From the two graves, bear right, around the front of the church, passing through

the magnificent porch beneath the tall spired tower. In the mosaic pavement is a

small, circular device containing the names of Samuel, Joshua and John Fielden.

On reaching the far end of the building, bear right, to where the main entrance to

the church stands near a magnificent 'rose' window.

Todmorden Unitarian Church.

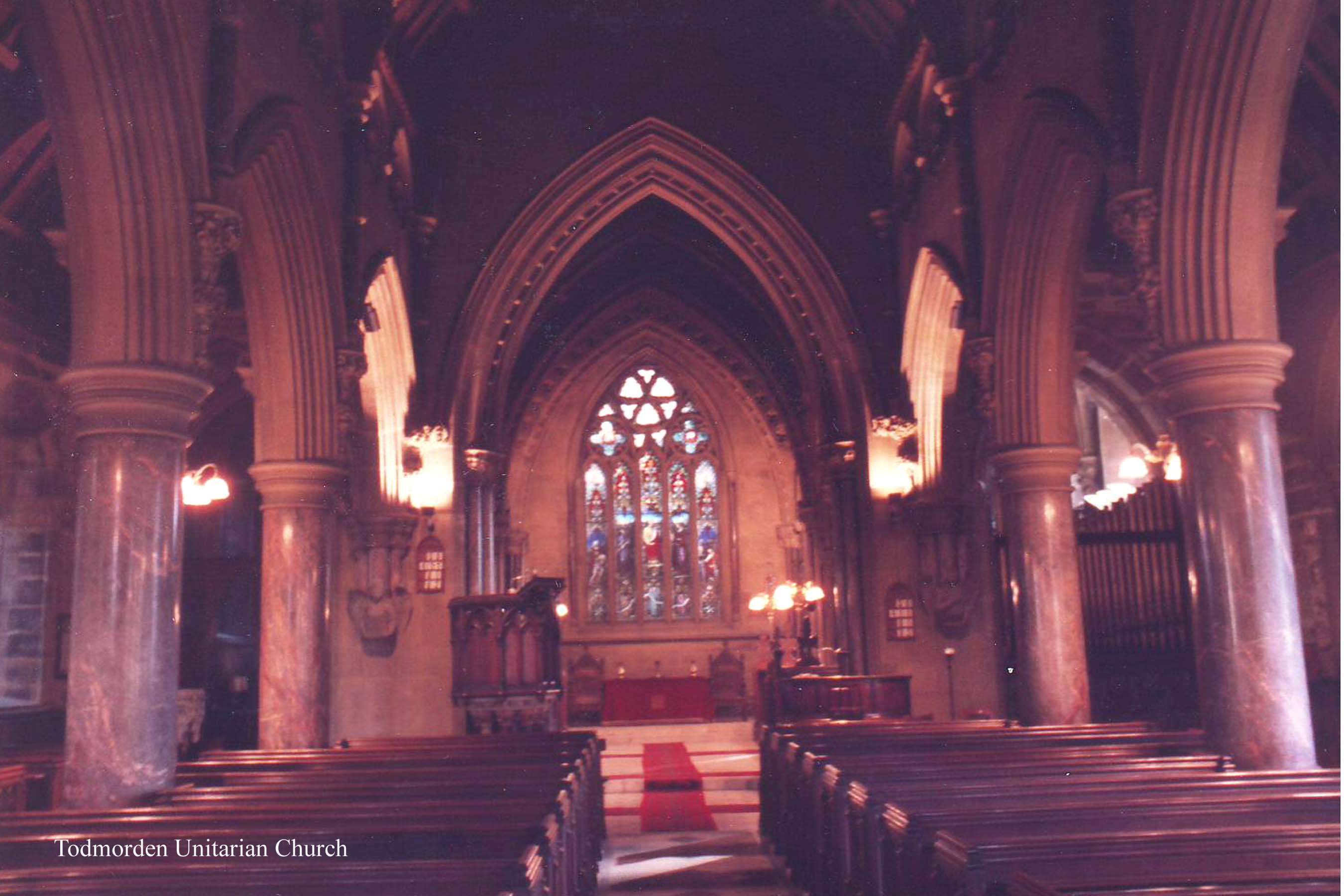

Todmorden Unitarian Church was built by the three Fielden Brothers,

John, Samuel and Joshua, in memory of their famous father, 'Honest John' Fielden

M.P. The first sod was cut in April 1865, and the corner stone was laid by Samuel

Fielden on December 23rd 1865. Prior to its opening the structure was complete in

almost every detail, and the gathering of 800 people who met for the offical

opening on April 7th 1869 saw the church as a finished work of art. Like most of

the Fielden buildings in Todmorden the Unitarian Church was designed by

the Westminster architect John Gibson, who created a Gothic style church of

remarkably fine taste. (Victorian 'Gothick' was very often quite the opposite.)

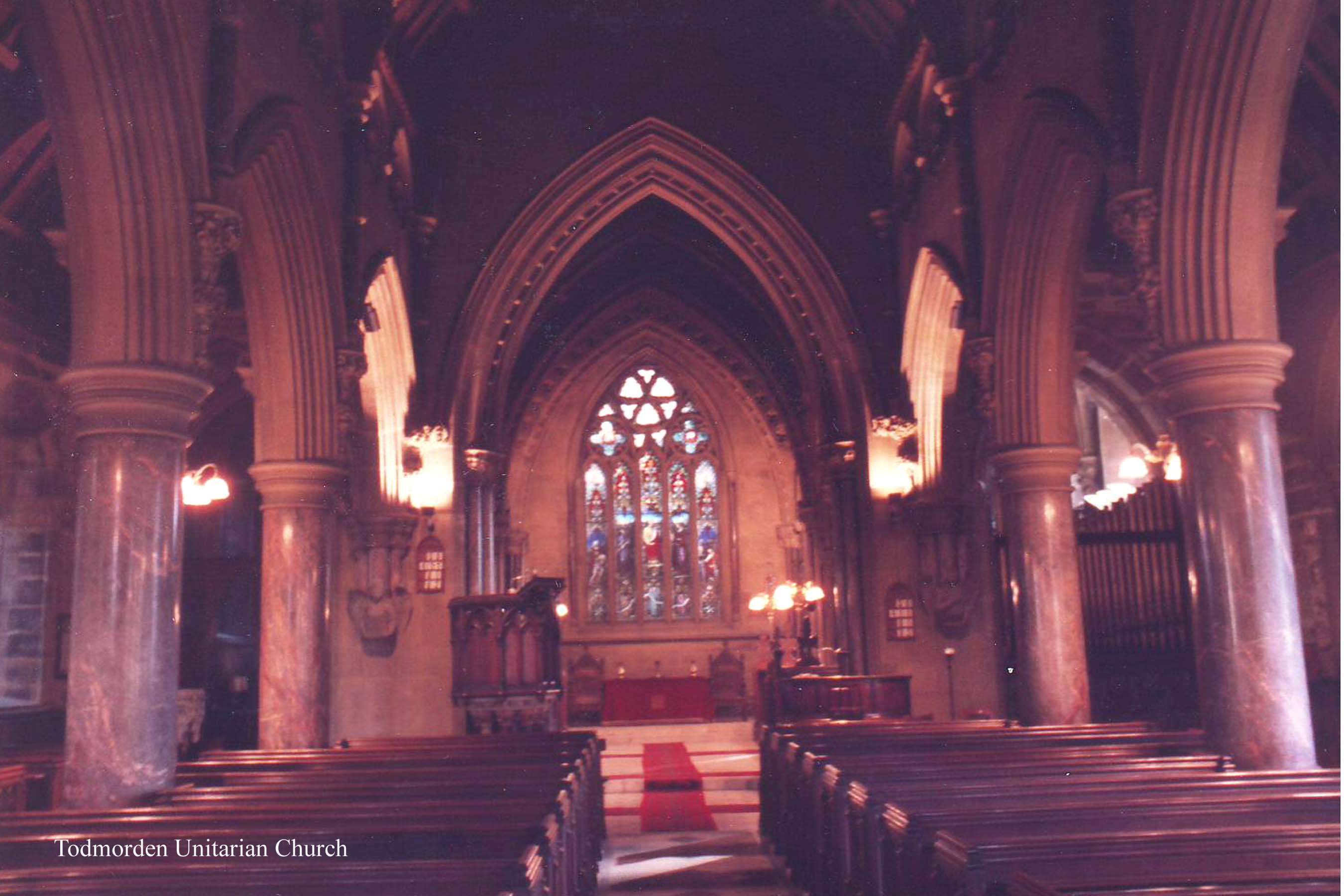

"Internally this massive church, constructed in stone, marble and oak, is 128

feet long and 46 feet wide. The magnificent spire is 196 feet in height. To ensure

its safety the steeple has its foundations 30 feet down into the ground, and the

pinnacles increase the stability of the tower by their downward thrust. The lofty

nave with its two aisles has seven pointed and moulded arches on each side,

springing from pillars of Devon marble six feet in circumference. Each window in

the nave has its arch finished with the carving of a human, alternately male and

female. A unique feature of its oak roof is the insertion of a number of small

windows admitting light. These cannot be seen from the outside. On the south side

of the chancel is the vestry, originally planned as a mortuary chapel, and on the

north side is the organ chamber and original vestry. The rose window at the

western end of the nave is one of the finest features of the church. In some lights

the 35,000 pieces of glass used in its design gleam like a precious jewel. The only

other windows of stained glass are those in the chancel, which contain

representations of biblical incidents. These windows, with colours rich and

glowing, were the work of M. Capronnier of Brussels. The beauty of this

church has not been spoiled by the addition of unsuitable memorials. It

contains only four, one to the memory of those members who gave their lives in

the Great War 1914-18, and the other three to the Fielden brothers by whose

munificence the church was built . . ."

So much for the "guide book" details. Now to the sad reality. On my second

visit here I was lucky enough to arrive when the custodian of the church, Mr.

Rushworth, was showing round an architect and a surveyor from London, who had

been requested to come and inspect the fabric, judge what repairs were necessary,

and estimate the cost. Mr. Rushworth explained to me that the church is normally locked

because of repeated acts of vandalism carried out by the youth of the neighbourhood. Only

recently the church had been broken into and a lot of damage done. My guide

informed me that he had once worked as a secretary at Fielden's Mill. He showed

me pews at the front of the church which were slightly larger and more

comfortable than the others (I wouldn't have noticed the difference had it not been

pointed out to me). These were obviously the Fieldens' own private pews.

Unfortunately the future prospects for this beautiful building are none to good.

Not only has the church been vandalised, but the lead on the roof has become so

decayed that it is raining in, with resultant damage to the church's fabric. Mr.

Rushworth informed me at the time that they had put in for a grant to restore the

church, but did not feel that it would be of much use, as the cost that was estimated

for the repair work was in excess of 50,000 pounds (it only cost 36,000 pounds to build).

Sad to say, this magnificently beautiful building is today something of a white

elephant. Built in an age of Victorian wealth and opulence, the Fielden brothers

would never have imagined that perhaps one day future Unitarians might be quite

unable to keep up to this grandiose memorial to their father's memory. Its very

scale and magnificence denies it any use other than that for which it was intended.

If it were smaller, and older, there would be lots of potential uses and sources of

revenue to ensure its continued survival. Alas, this is not the case. It remains, a

massive, decaying church with only a small congregation.

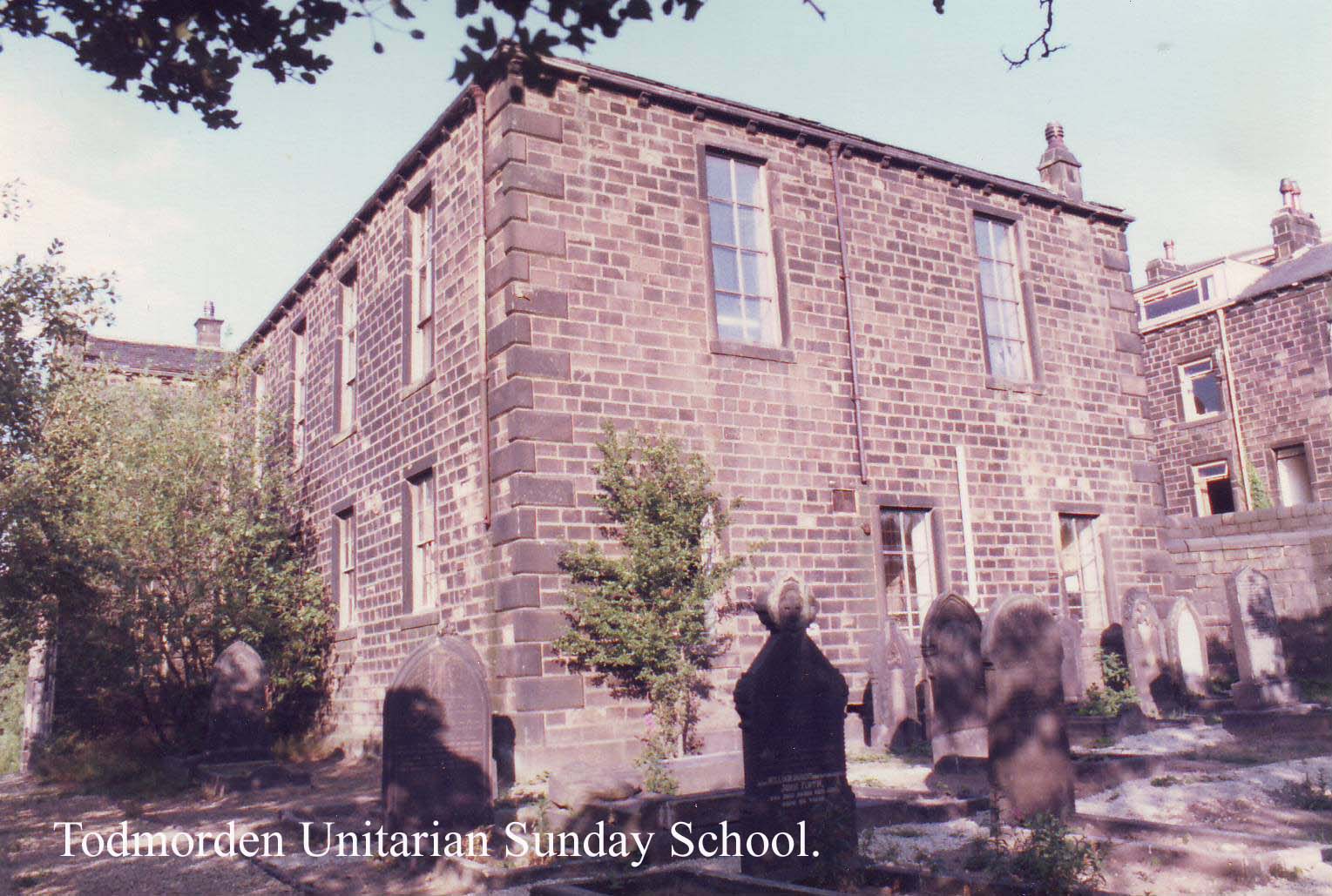

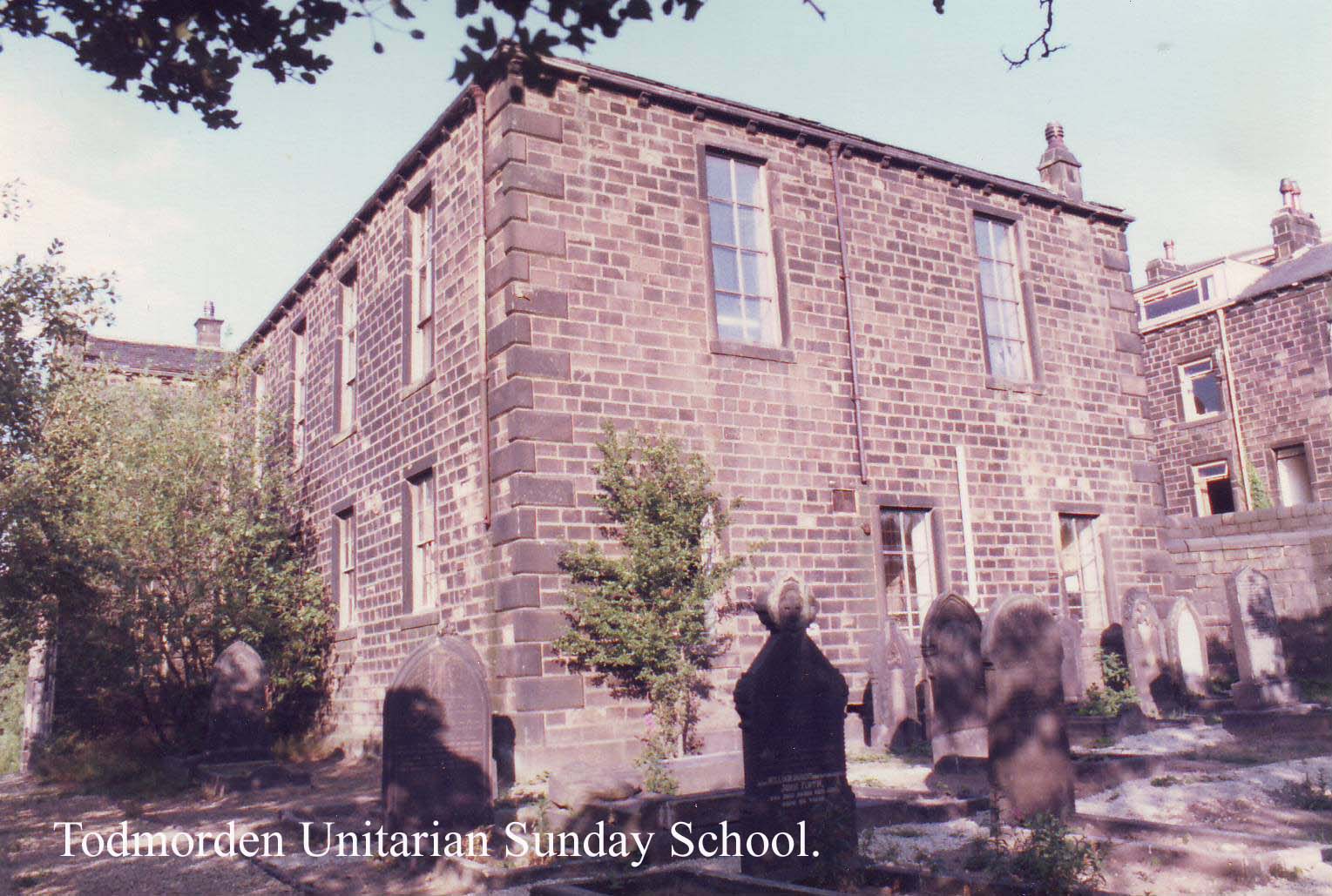

The irony of the situation is that a few years ago, when faced with the choice of

selling either the old Sunday School or the church, they sold the former on the

grounds that it would be unthinkable to part with the magnificent latter building.

The Sunday School (which was the original Unitarian Chapel) is now a workshop

and the Unitarians are beginning to regret that they sold it. It was smaller, more

adaptable and historically of greater significance than its more magnificent yet less

venerable successor. There would have been far less difficulty in attracting funds

to restore and modernise it. Now, alas, they are left with an unspoilt, unaltered,

architecturally beautiful 'white elephant', and an enormous financial headache.

There is light at the end of the tunnel though; at the time of writing, a grant has

been obtained, and there are plans currently afoot to turn the church into a

Fielden museum and exhibition centre. Hopefully they will succeed and

Todmorden Unitarian Church may be rescued from oblivion before it is too late.

From the entrance porch of the church return to Honey Hole Road and pass

Meeting House Cottage on the right. Here was the Banktop Quaker Meeting House

which was built in 1808 after the meeting house at Shoebroad had been taken down. A

little further on, near a high wall and a trough on the right, bear left past modern

railings to an iron gate in a stone wall. This leads into the graveyard of

Todmorden Unitarian Sunday School:-

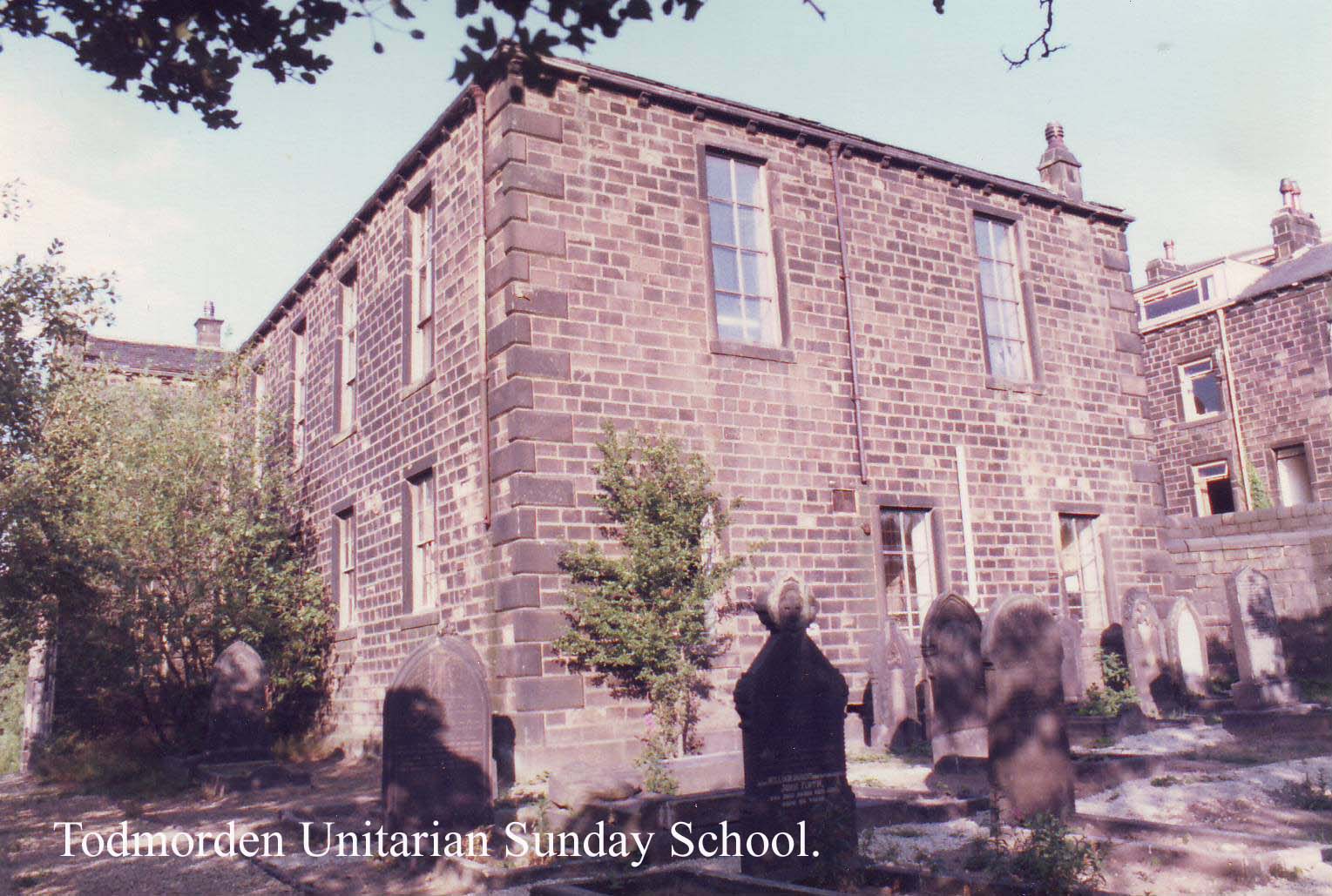

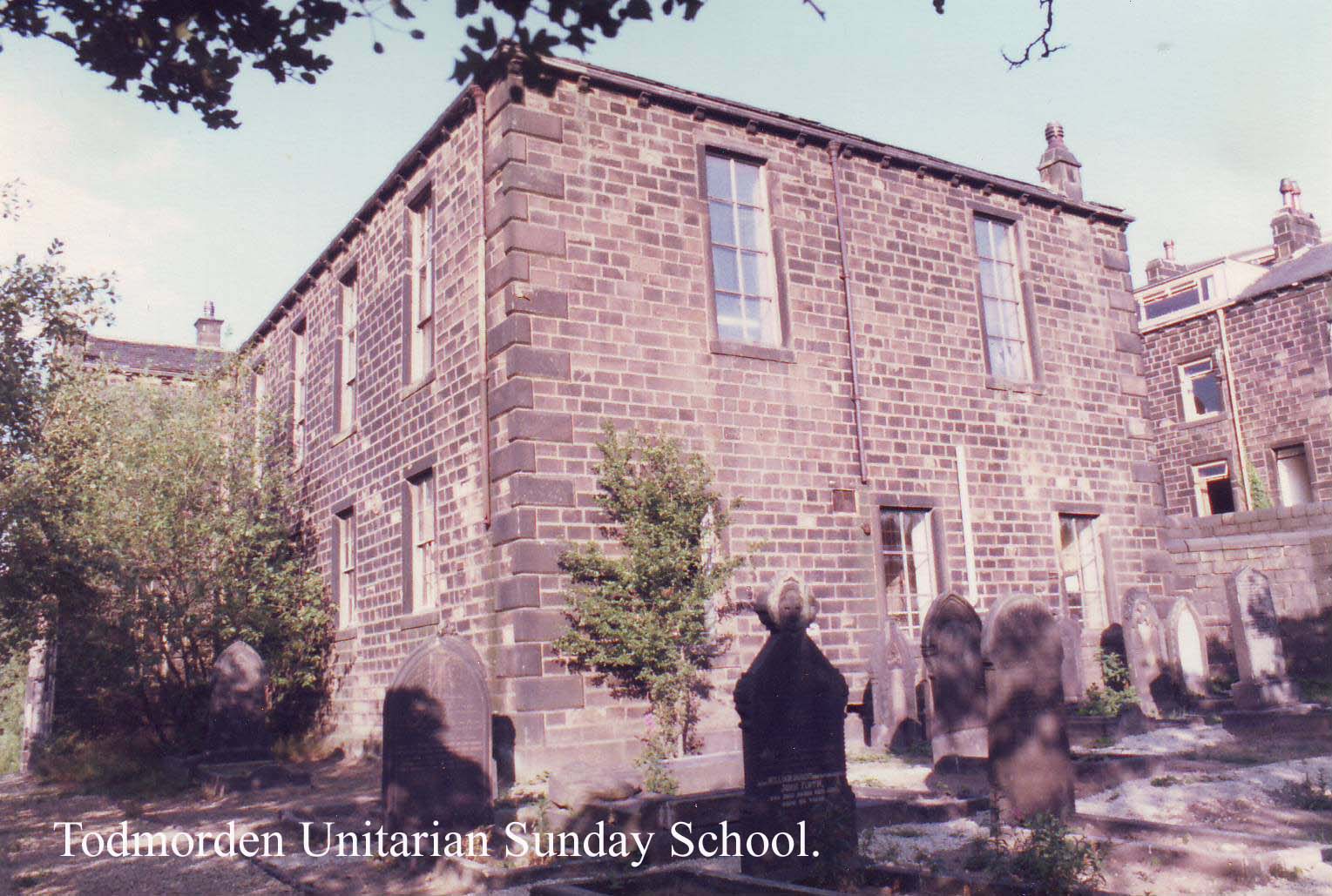

Todmorden Unitarian Sunday School.

The first thing we encounter at the old Sunday School is 'Honest John' Fielden's

grave, which lies almost at your feet as you enter the graveyard. It is substantial

but plain, being little more than a large expanse of gravel surrounded by four

kerbstones.

Why, you might ask, was this relatively humble spot chosen as the last resting

place of such a distinguished man as 'Honest John' Fielden? Surely it would

have been more fitting to inter his remains in a more suitably grandiose tomb, sited

in the magnificent church that was erected nearby to his memory? The reason is

simple. The Old Sunday School was the original seat of Unitarian worship in the

area and was the building that 'Honest John' knew and loved during his lifetime.

Indeed, 'Honest John' Fielden's role in the development of the Unitarian Faith in

Todmorden cannot be ignored, for without his enthusiasm and support that faith

might well have foundered and passed into oblivion.

The story of local Unitarianism begins in 1806 with a schism among Methodists in the

Rochdale area. This was caused by the expulsion from his ministry of the

Reverend Joseph Cooke, who was removed from the Rochdale Methodist Circuit

on account of his heretical opinions. Joseph Cooke was both young and

popular, and his expulsion caused a secession from the ranks of Methodists

in Rochdale, Padiham, Burnley and Todmorden, which were the areas where

Cooke preached. These people gathered into Bible Reading Societies known as

"Cookite" Congregations. Cooke's friends built for him the Providence Chapel in

Clover Street, Rochdale, from which centre he established a 'circuit' and

ministered to the various Cookite groups in neighbouring towns and villages. He

died in 1811 aged 35. After his death Cookite numbers dwindled and those that

remained became known as Methodist Unitarians, and it was to one such group, in

Todmorden, to which John Fielden, the Quaker, was attracted.

In 1818 the renowned Unitarian Missionary, the Revd. Richard Wright,

preached at Clover Street when some Todmorden hearers were present. They invited

him to come and preach in Todmorden, and when he did so the local Cookite group

were deeply impressed, realising that Unitarianism and their own beliefs were pretty

much in agreement. Equally impressed by his meeting with Richard Wright was

John Fielden, the Quaker millowner, who was converted to Unitarianism as a

result. Already renowned for his sincerity, ability and work as an educationalist,

John Fielden was the natural choice to lead this small band of Todmorden

Unitarians, and the first result of Wright's visit was the formation of the group

into a "Unitarian Society", with 'Honest John' as its most influential member.

Fielden invited local Unitarian Ministers to visit Todmorden on a fortnightly basis

and was successful in his endeavour. The Society at first met in a meeting room at

Hanging Ditch, but, as they prospered and grew in number they resolved to build a

Meeting House "Where the worship of God in one Person shall be carried on and a school

taught."

Thus it was that in 1824 the Todmorden Unitarian Chapel (which later became the

Sunday School) was opened on Cockpit Hill, with an outstanding debt of about

500 pounds. Times were hard for the cotton operatives who were the main support of

the chapel. The trustees, finding the situation a burden, begged to be relieved of

the office. 'Honest John', in typical Fielden fashion solved the problem by

buying the Chapel, School and all accoutrements for 480 pounds. He appointed a

regular Minister and paid his salary. This Minister was to also act as Schoolmaster

in 'Honest John's' own Factory School at Waterside, which we encountered earlier in

our travels. 'Honest John' superintended the Sunday School in person, beginning at

9.30 am with prayers, service, and scripture reading; followed by the 'three Rs',

spelling and history. From 1828 onwards Fielden provided a day school with

accomodation for 100 children between the age of four and the time of going to

work. A fee of 2d per week was charged. This covered the cost of materials, the

teacher's salaries being paid by 'Honest John'.

On 29th May 1849, after a distinguished but alas rather brief Parliamentary

career, 'Honest John' Fielden died at Skeynes in Kent and was brought to

Todmorden to be buried in the yard of the chapel he had loved so well. The

funeral took place on 4th June, and according to the account published in the

Ashton Chronicle, it was quite a substantial affair:

"The remains of Mr. John Fielden of Centre Vale, late M.P. for Oldham, were

interred on Monday in his own chapel yard at Honey Hole. The funeral procession

began to move from Centre Vale about 12 o'clock, headed by the minister, Mr. James

Taylor and the Revd. J. Wilkinson of Rochdale, followed by the principal gentlemen of the

neighbourhood ... The hearse was followed by two mourning coaches containing his sons and

brothers ... these were followed by four other coaches, with relatives and intimate

acquaintances, among whom were Mr. Charles Hindley, M.P. for Ashton, and Mr. John and

Mr. James Cobbett. These were followed by a large procession of gentlemen and operatives

from Oldham, Bolton and Manchester, who had come unsolicited to pay a mark of

respect to their friend and benefactor. The road was lined with spectators from ... Centre Vale

to the chapel, and thousands were on the hillsides and the tops of houses to witness the sad

procession."

After 'Honest John's' death his three sons and their wives took over leadership of the

Unitarian Congregation, and in 1869, when the new church was endowed, a new school

was opened in the old chapel, which became the Todmorden Unitarian Sunday

School. The old chapel was further extended and modernised in later years. A stone over

the entrance reads:

"To the memory of Samuel, John and Joshua Fielden;

constant benefactors of the Unitarian Church and

School this stone was laid by Salfred Steintha

June 17th 1899."

Today the Sunday School is a workshop, yet another chapel building fallen to the

ravages of today's unbelieving consumer society. In the 19th century both family and

community life was centred on the chapel ... today's urban man dedicates his spare time to

TV. The material has replaced the spiritual, and in thousands of demolished or secularised

chapels all over the region we are witnessing the "Fall of Zion". Today's society, living in

the shadow of nuclear annihilation, sees no tomorrow, and it is hardly surprising to find that

the solid faith and confidence in the future enjoyed by our Victorian forebears is singularly

lacking today.

Chapels have now become workshops, recording studios, offices. There has even been

a recent attempt to turn one into a witches' temple, and a century ago this would not

only have been impossible but inconceivable! Today we are no longer subject to the

tyrannical restrictions that were imposed on us by the blinkered guardians of Christian

morality, but equally we are no longer able to enjoy the strength, fellowship and

confidence that they took so much for granted. In rejecting the bad, alas, we have also

rejected that which was good.

Before leaving the Sunday School yard take a look at the grave of James Graham,

blacksmith of Dobroyd, whose headstone bears the following inscription:

"JAMES GRAHAM of DOBROYD, Todmorden.

Born March 18th 1837

Died February 12th 1876.

My sledge and hammer lay reclined my bellows too have lost their wind

my fires extinguished and my forge decayed my vice now in the

dust is laid.

My iron and my coals are gone,

my nails are

drove, my work is done;

my fire dried corpse lies here at rest

my soul is waiting to be blest! "

From the graveyard descend steps to:-

The Golden Lion Inn.

One of the older local hostelries, the Golden Lion has witnessed much of

Todmorden's history. Situated in the old township of Langfield, it has an old

drainpipe bearing the date 1789 on its rainwater head. An old coaching inn, it was very

important in the days of turnpikes, the turnpike came to Todmorden in 1750, when its

innkeeper was both postmaster and coach proprietor. Both the 'Shuttle' and

'Perseverance' stagecoaches called here on their way to Halifax. The Golden Lion was the

scene of many gatherings of local importance. It was for many years the meeting

place of the Freeholders of Langfield Common, and as such was greatly involved with

both the building and later re-building of Stoodley Pike Monument.

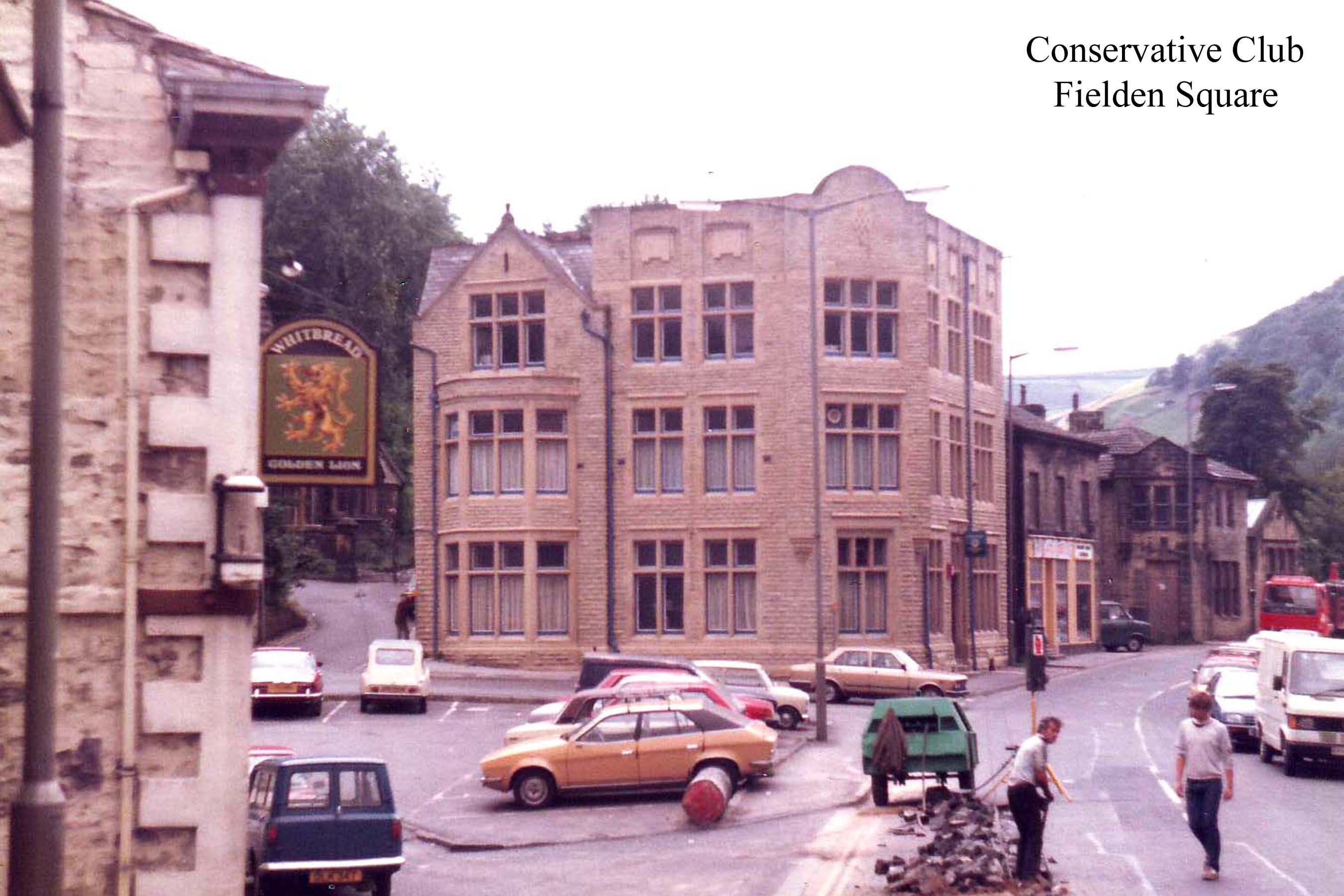

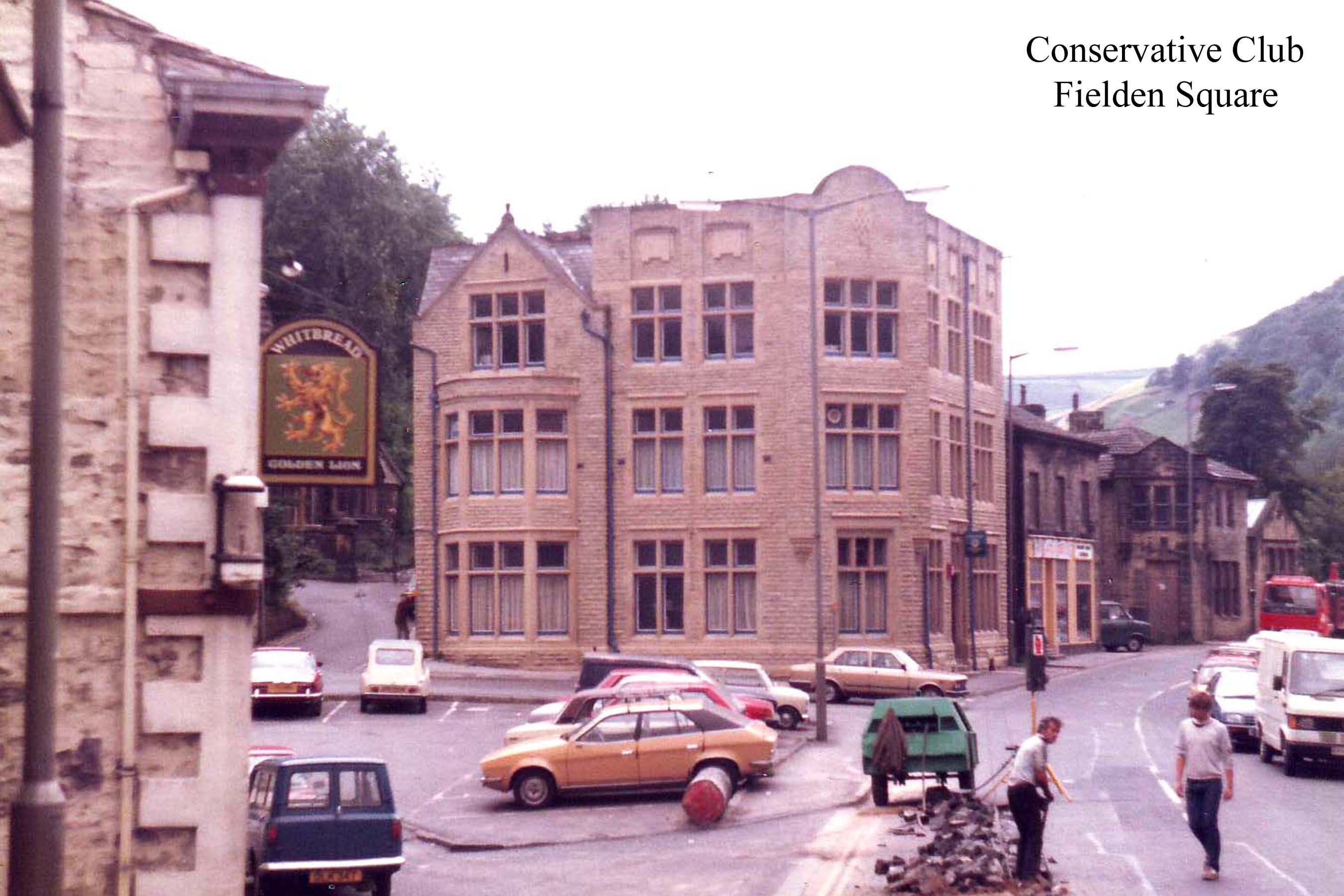

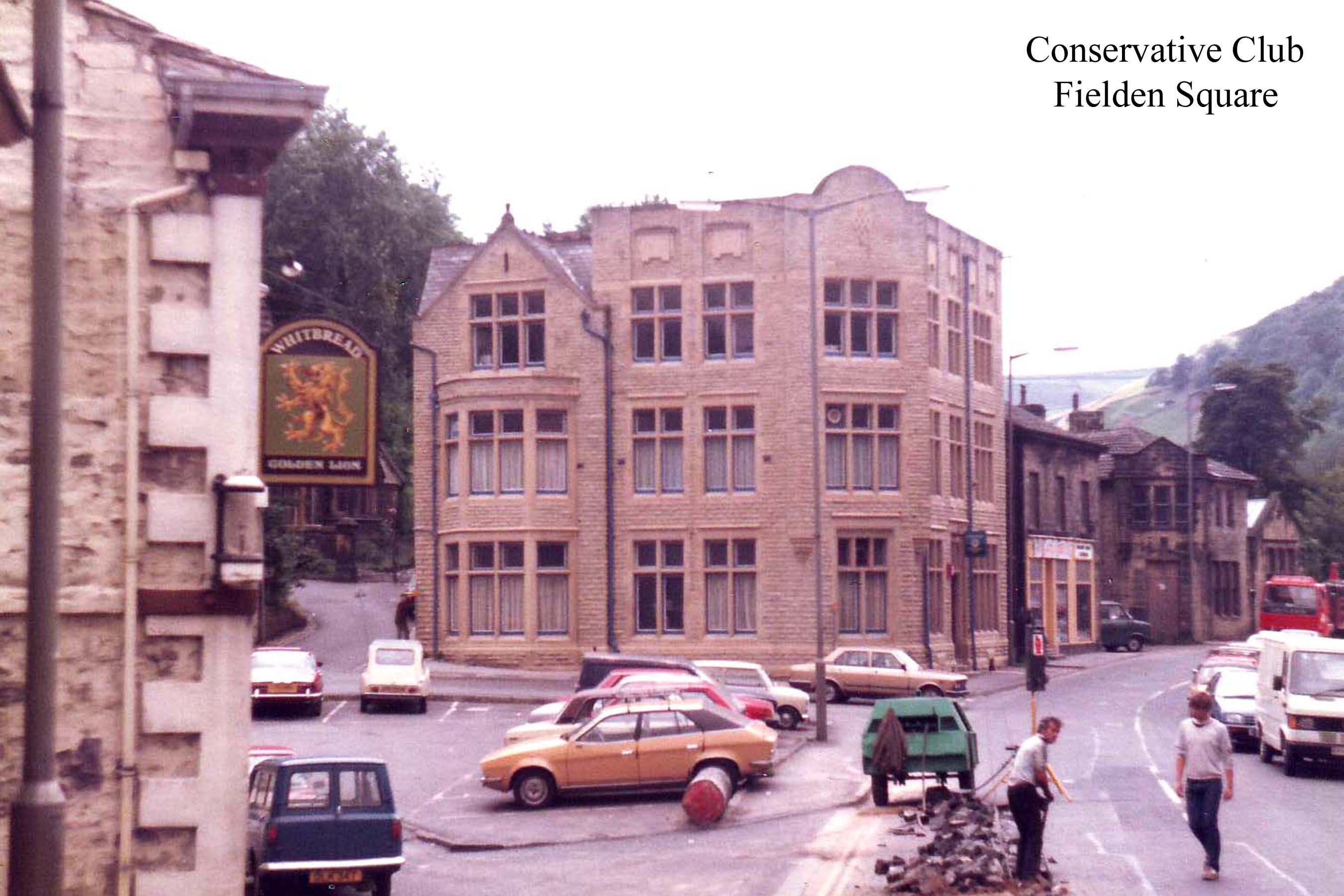

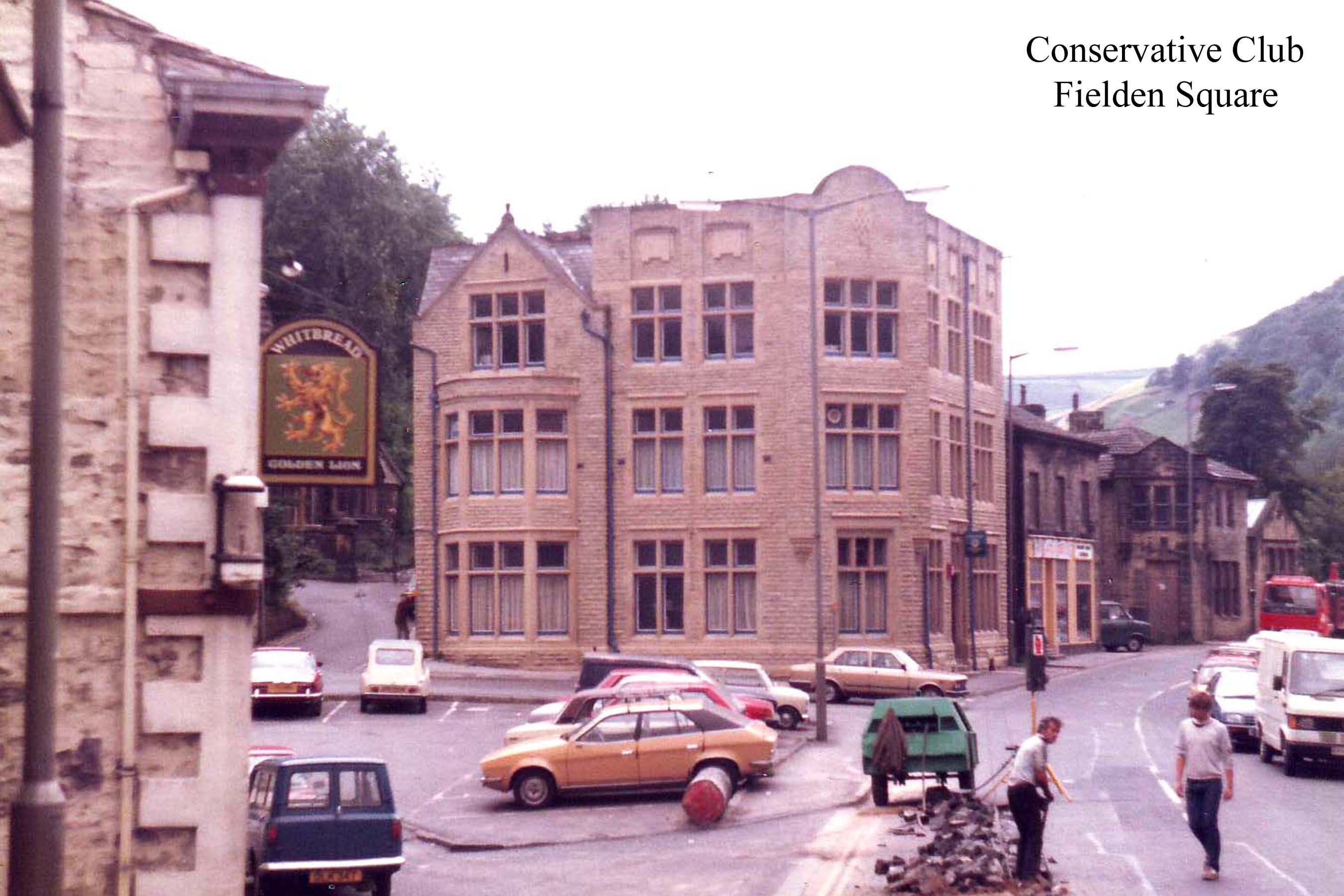

The Conservative Club.

Across the square from the Golden Lion stands the Conservative Club. This was

originally opened in 1880 as the Fielden Hotel and Coffee Tavern, and was, in its day, a

stand for temperance in an area rich in taverns and hard drinking. It was built through the

generosity of John Fielden J.P. of Dobroyd Castle. Closing its doors in April

1913, it reopened afterwards as a Conservative Club, the function it retains to

this day. Outside it stood the statue of 'Honest John' Fielden, which is now

situated in Centre Vale Park, at the very end of our journey.

From Fielden Square we pass through the heart of Todmorden to Centre Vale

Park and the end of the Fielden Trail. By now, your feet will be telling you that

you have nothing left to prove after having walked 99 percent of the route. "What is the

point of walking this extra distance into Centre Vale Park?", you will be saying.

You will have to walk back into the town centre when you've been there anyway!

Well, if that's how you feel you can go home now, but if you'll bear with me, I'm

sure that you will find the extra bit of walking required to complete the

Fielden Trail quite worthwhile, there are still some stories left to be told and some

ends to tie up.

From the Conservative Club follow the main road towards the centre of

Todmorden. After crossing the canal turn left up Hall Street to the grounds of

Todmorden Hall. The Fielden Trail passes the front of the house to emerge into Rise

Lane on the other side.

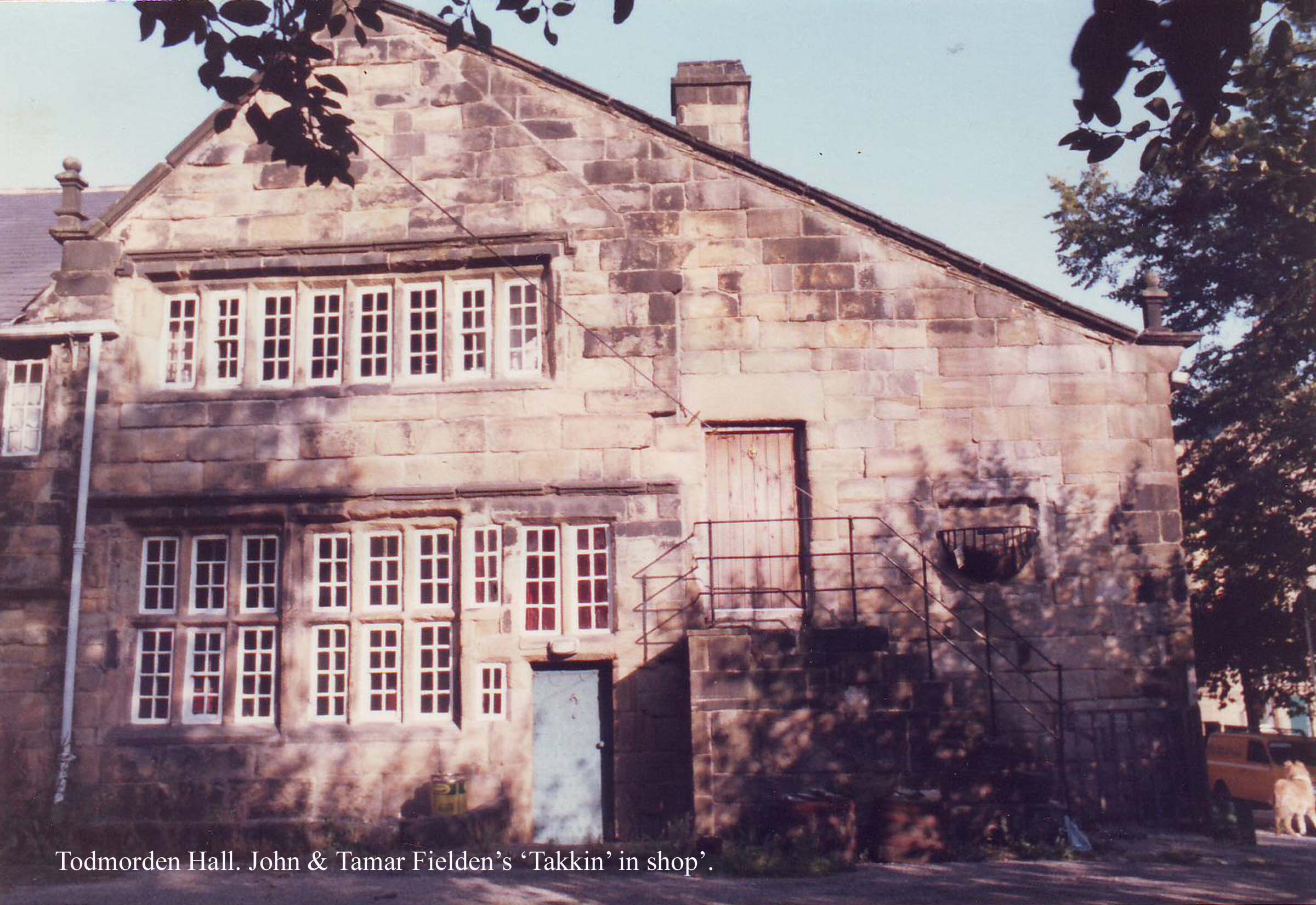

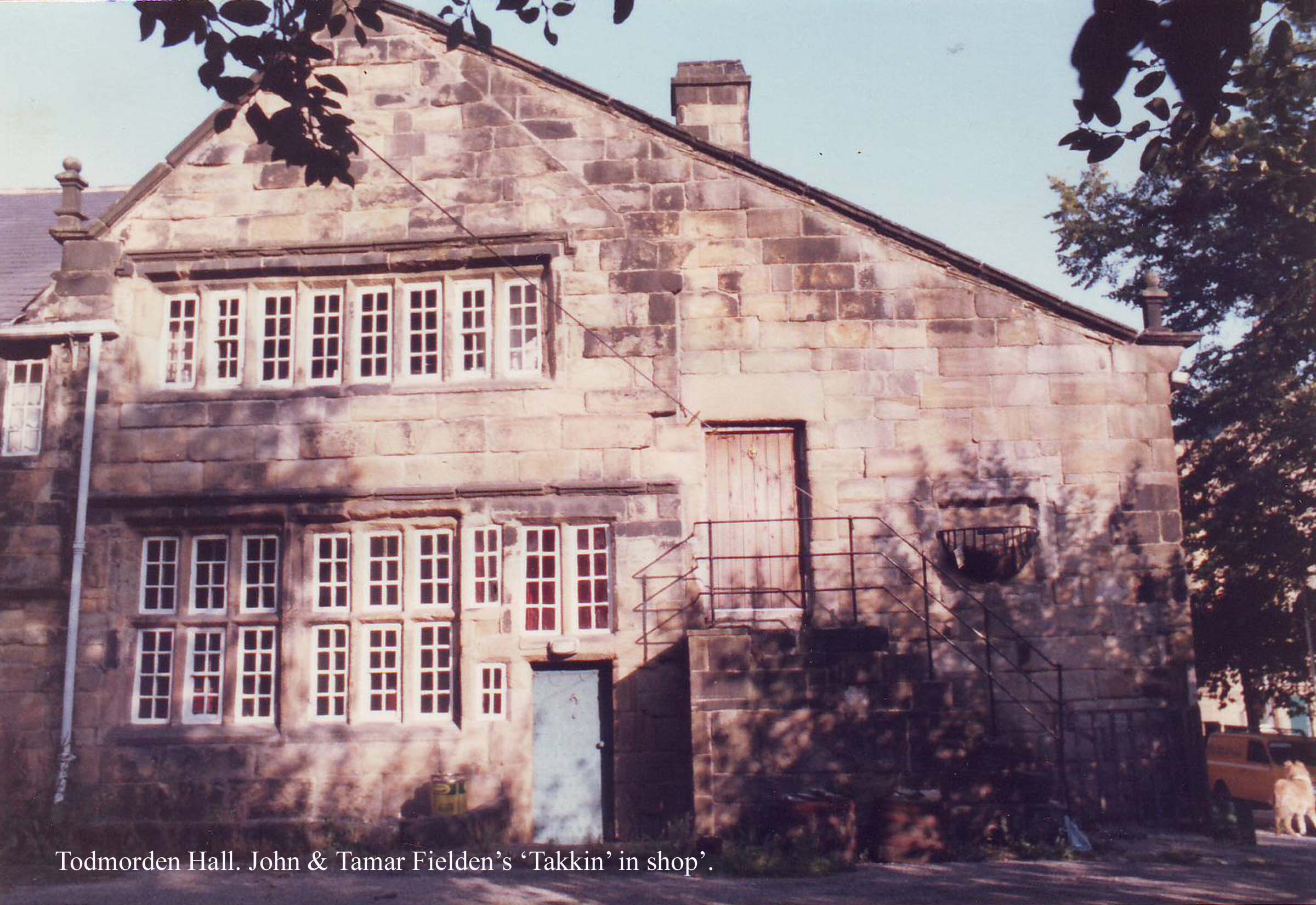

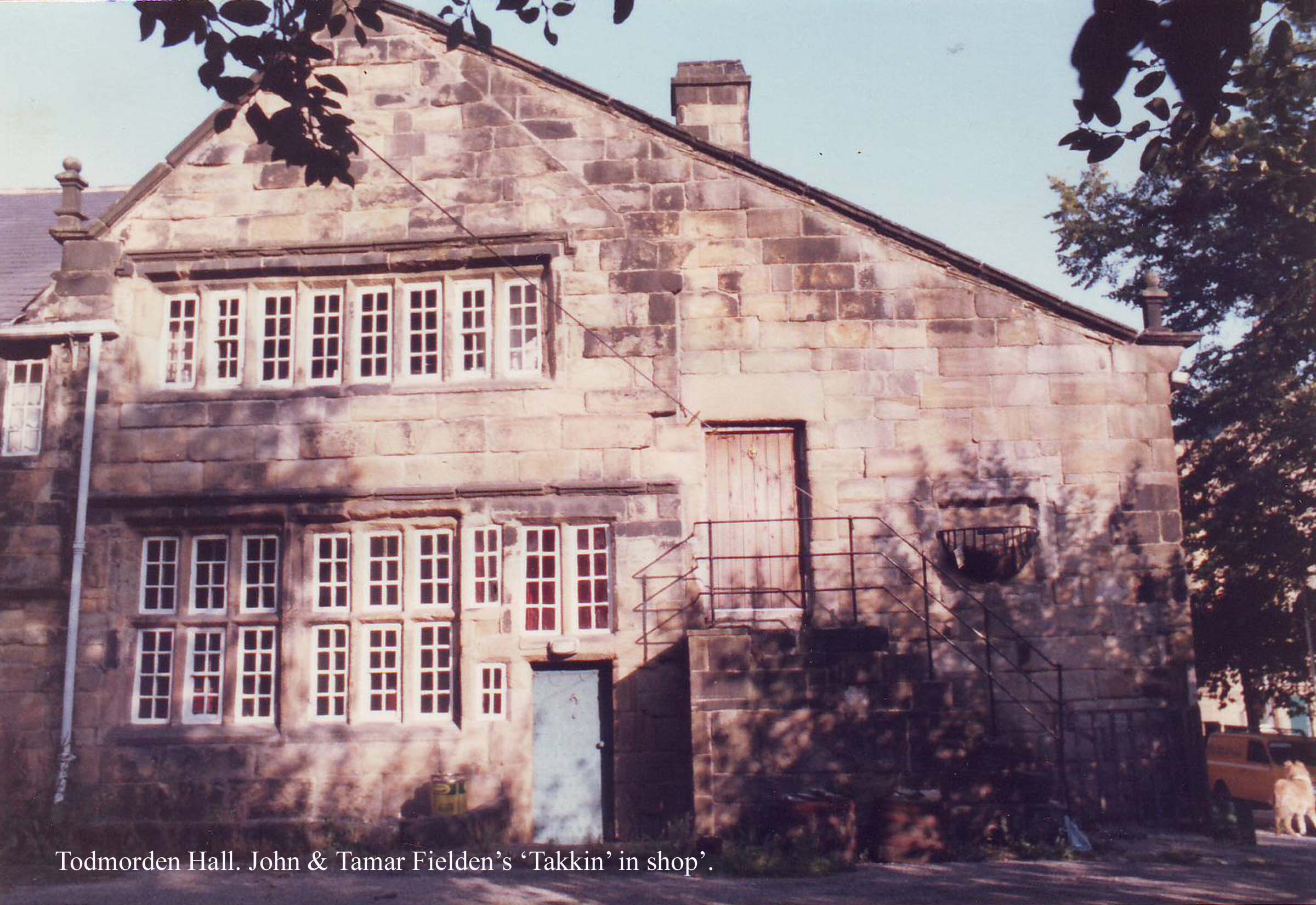

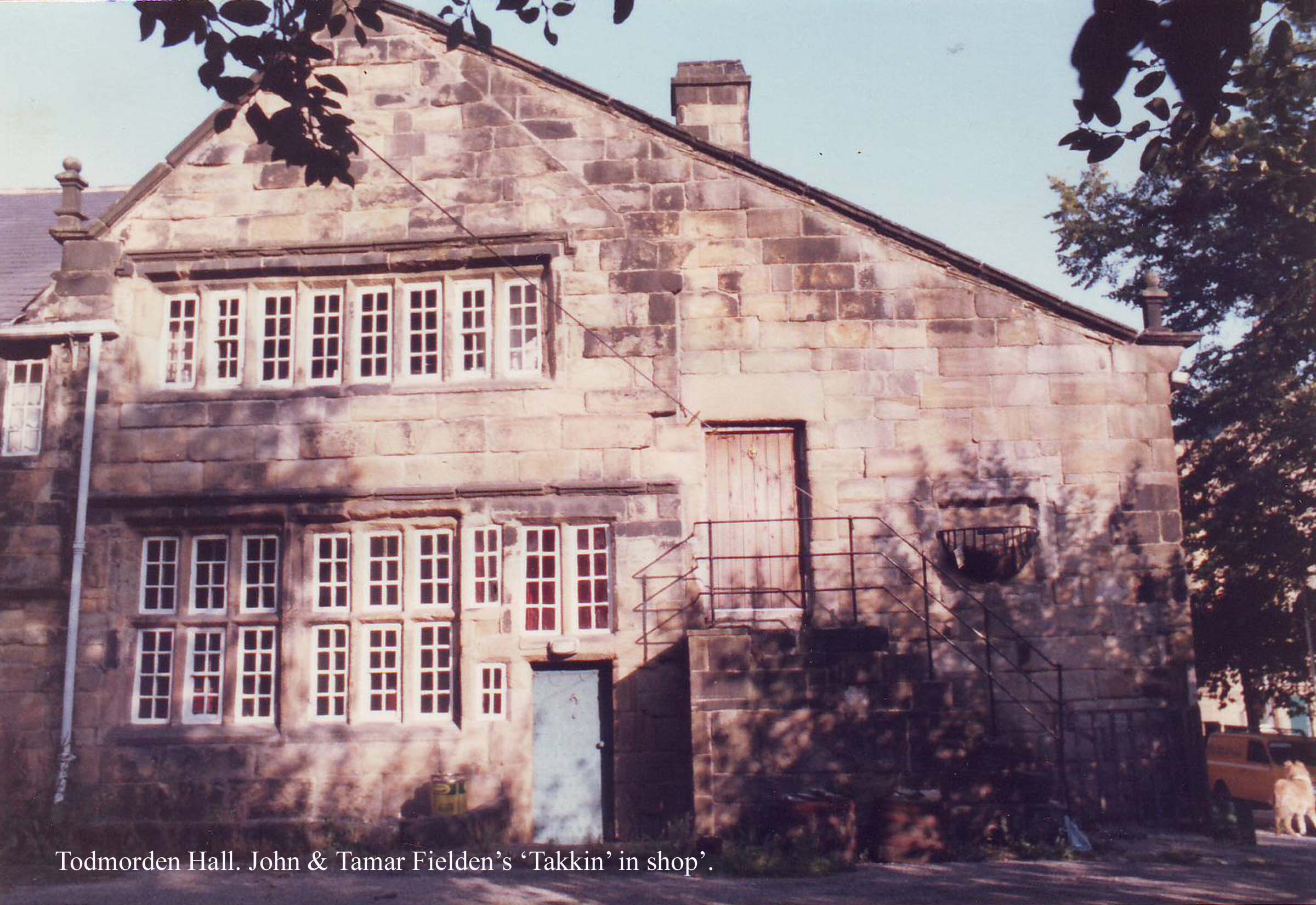

Todmorden Hall.

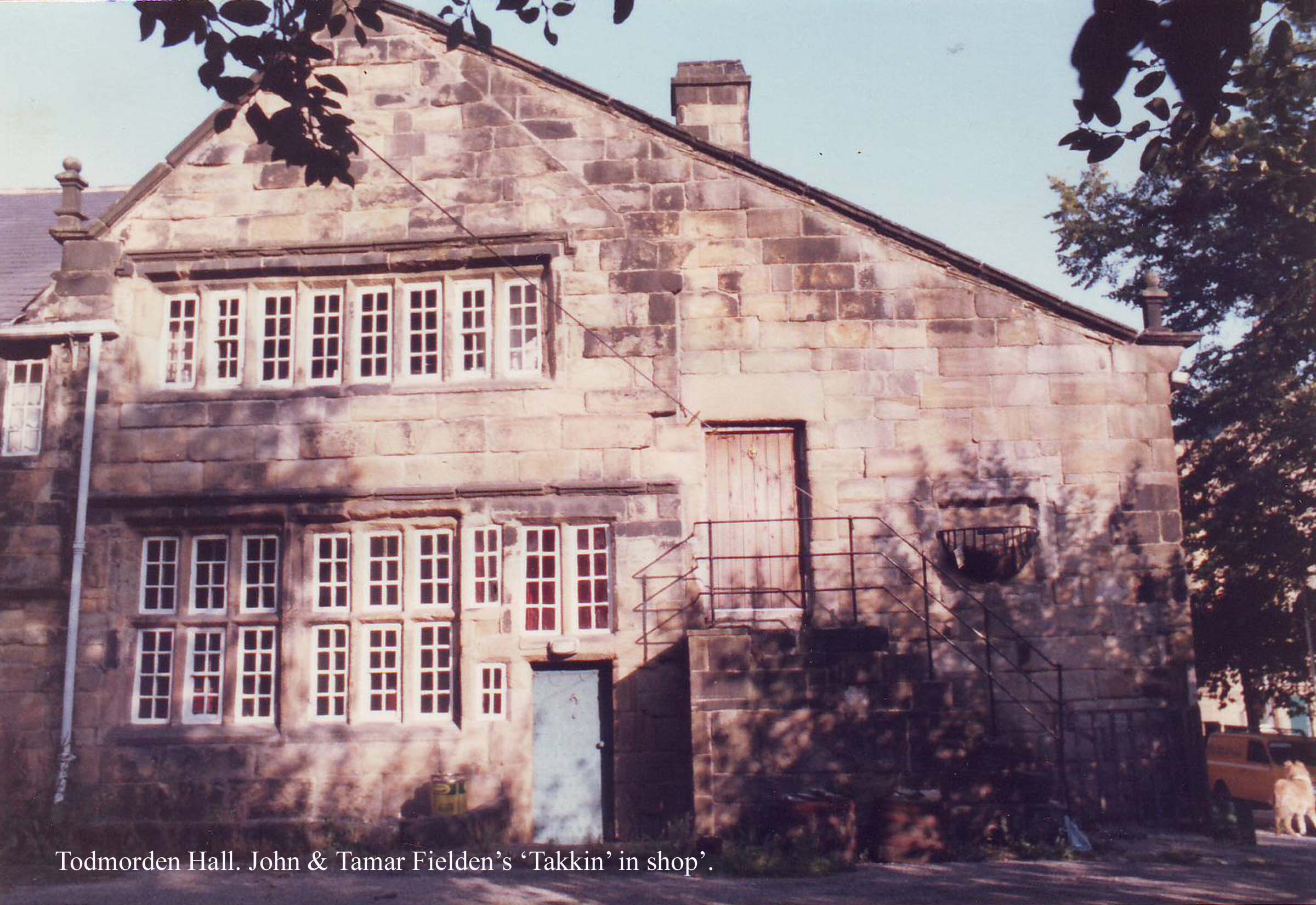

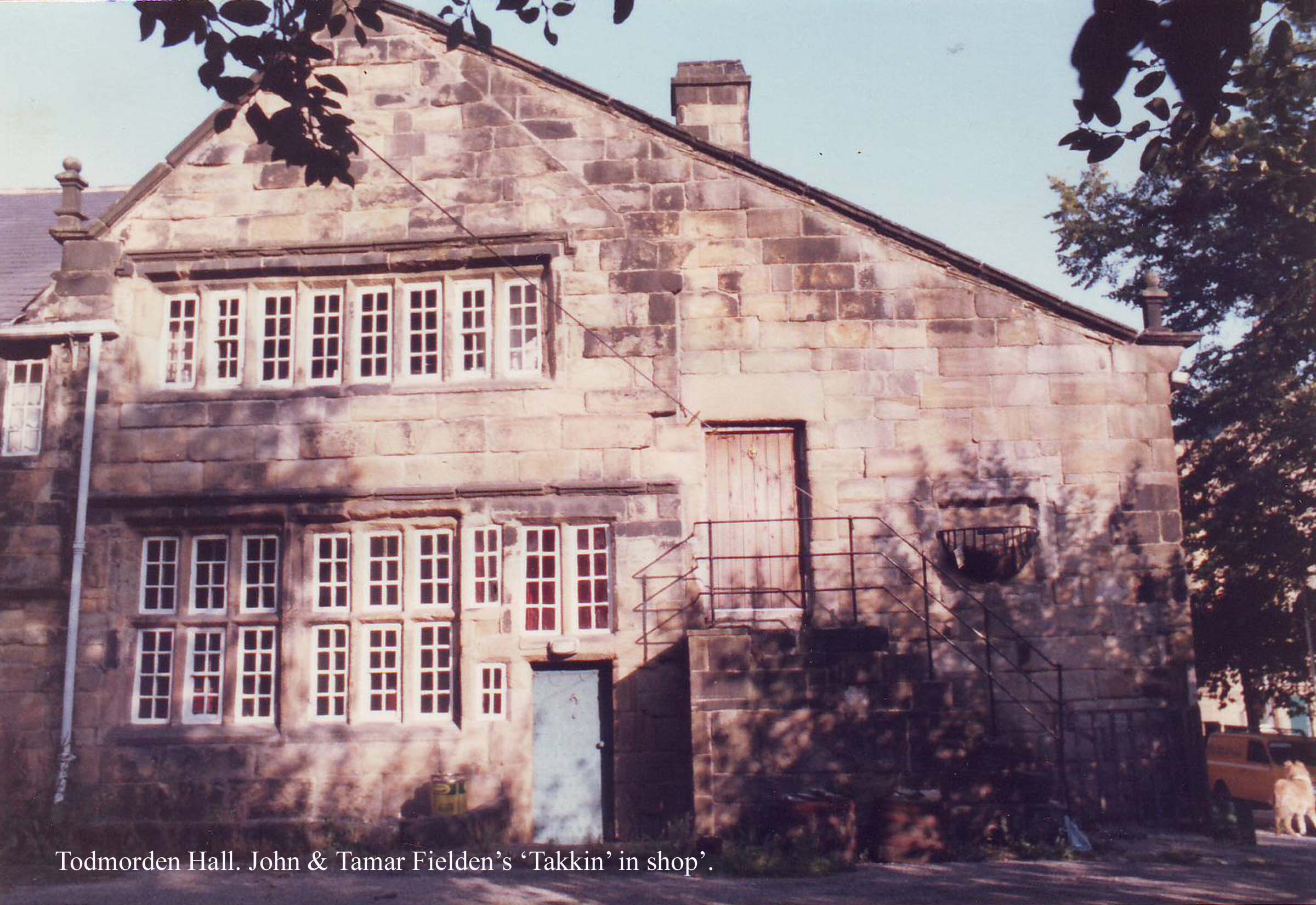

This magnificent house, formerly a Post Office and now used as a restaurant,

stands at the very hub of Todmorden's history. The present hall was rebuilt in

1603 by Saville Radcliffe, whose family had lived there for several generations. It

was a gentleman's house, built (by local standards) in the grandest possible style and

up to the 1700s it was the very heart of Todmorden, which at that time was little

more than the Hall, the Church, and a few cottages. Todmorden was unusual

in those days; a small valley community, rare in a district where almost all the

local population lived at a higher level on the surrounding hillsides. The main

arteries of communication also tended to avoid the valleys in those times; so

Todmorden was in many ways a quite untypical Pennine settlement.

By the 18th century Todmorden was growing, and the Hall passed into the hands

of John Fielden, brother of Joshua (I) of Bottomley. John lived here from 1703 to

1734. Besides Joshua, John also had three other brothers, Nicholas and Samuel of

Edge End, and Thomas of Hollingworth, all of them Quakers. In November

1707 John married Tamar Halstead of Erringden and they lived together at

Todmorden Hall. John Fielden was a wealthy man: a prosperous

woollen clothier who extended the Hall and built a "takkin' in shop" at the back,

reached by a flight of external steps, which may still be seen. In the days of the

handloom, weft and warp were given out to the weavers, and later the finished pieces

were "taken in" here, hence the name. The weavers must have been a far cry from

the gentry who would have visited the Hall in the days of the Radcliffes. John

and Tamar Fielden must have been an industrious couple, for besides being

deeply involved in the woollen trade they were also responsible for building the

White Harte Inn which, like the Golden Lion, was witness to much of Todmorden's

local history.

Tamar Fielden died on 8th January 1734 and was buried at Shoebroad. Her

husband followed her on 20th May in the same year, having already made out his

will in February. Their marriage had been childless, and John's estates, which

also included Edge End, passed to his nephew Abraham, who in turn died at

Todmorden Hall on 14th May 1779 aged 74. Like his uncle he was buried at

Shoebroad. After this time the Hall passed from the Fieldens, later to become the

residence of Mr. James Taylor Esq. the Magistrate, during which time the Hall

suffered damage at the hands of the Anti Poor Law rioters. Now, in the 20th

century, after a long career as a Post Office it has become a restaurant, and very

attractive it is too, especially after a

long, tiring hike. (But I wouldn't go in there wearing hiking boots if I was you!)

Leave the hall grounds and turn left into Rise Lane, which leads to the station,

and pass behind the church and the White Harte Inn. There was a temporary

railway station here until 1844, but the present building dates from 1865. The

massive goods yard retaining wall above the canal was built in 1881, and

Fieldens were involved with much of this development. Both Thomas Fielden,

'Honest John's' brother, and his nephew Joshua were directors of the Lancashire

and Yorkshire Railway. On 1st March 1841 Thomas Fielden complained about the

practice of compelling 'waggon passengers' to arrive at the station ten minutes

early. He was, it is said, a constant thorn in the flesh of the Railway Board's

Chairman. Suggestions he made for improving the comfort of second and third

class passengers were greeted with derision, and at some stations the

following notice appeared:

"The Companies Servants are strongly ordered NOT to porter for waggon

passengers . . ."

(Not even the railway companies, it seems, were spared the endless efforts of the

Fieldens to improve the lot of the lower classes!).

The White Harte.

Opposite the railway station stands the rear of the White Harte. The pub looks

modern and indeed it is, being built on the site of John and Tamar Fielden's

original White Harte which was demolished in 1935. The original pub was built in

1720 and was also known as the New Inn. It was in front of this inn that the first

Todmorden market was established in 1801; and later, between 1821 and 1851,

when George Eccles and family occupied the inn, a court of Petty Sessions was

established, and held upstairs in a room used by the local Freemasons for their

affairs. As a result, when anyone had to appear in court, it was referred to as "goin' up

Eccles' steps!"

In December 1830 'Honest John' addressed a meeting at Lumbutts which

petitioned Lord Radnor and Henry Hunt in support of Parliamentary

Reform, to which Earl Grey's new ministry was pledged. A month later,

Fielden presided over another assembly, here at the White Harte, to found a

"Political Union". Thereafter the Todmorden men joined their fellows in a

network of Political Unions dedicated to Parliamentary Reform. Their good faith

was rewarded, and in 1832, 350 reformers held a banquet to celebrate the passing

of the Reform Bill, with John Fielden in the chair. A free meal was also

provided for 3,000 of Fielden's workers at his own expense. As a result of this reform

'Honest John' was elected first ever M.P. for Oldham, and embarked upon his

campaign to secure for the oppressed operatives of the northern mills a Ten

Hours Bill. Here, at the White Harte an important chapter in the annals of English

social history was begun.

Beyond the White Harte bear left, and follow the route under the viaduct and

up 50 steps (Ridge Steps) to emerge on the 'Lover's Walk'. Soon terraced

housing and Christ Church (scene of dreadful murders in 1868) appear on the

right. Continue onwards, into Buckley Wood to arrive at the site of:-

Carr Laithe.

Here at Carr Laithe in Buckley Wood once stood a farmhouse which was the setting

for a romantic but rather sad episode in our "Fielden Saga". It was the home of

John Stansfield, a poor farmer whose daughter Ruth was courted and married

by John Fielden J.P. of Dobroyd Castle, 'Honest John's' second son. It was a classic

"rags-to-riches-cum-Cinderella" story. When he and Ruth met she was a mere weaver

at Waterside. He sent her away to be educated, but alas, she could never adapt to

the Fielden's by now aristocratic lifestyle. She died, an alcoholic, on 6th February

1877 at the age of 50, and is buried at the Unitarian Chapel. In the same year John

Fielden remarried, taking as his second wife Ellen, the daughter of the Revd.

Richard Mallinson of Arkholme in Lancashire. John Fielden J.P. is buried, as we

have already mentioned, at Grimston Park near Leeds. Perhaps it is from this story

that the Lover's Walk derives its name? It would certainly be nice to think so.

From Carr Laithe follow the path, right, down into Centre Vale Park. Centre

Vale Park is the site of the final "Fielden Mansion" to be visited on our route.

Centre Vale was the first 'great' house of the Fielden family; a Georgian styled

mansion which was the residence of 'Honest John' Fielden in later life, after he had

sold Dawson Weir. (By the 1840's Dawson Weir was in the hands of the Holt

family.) It ultimately became the residence of his eldest son, Samuel Fielden,

until his death in 1889, after which his wife, Sarah Jane lived there until her death

in 1910. In the Great War the house became a military hospital, and was eventually

purchased, along with its estate of 75 acres, by Todmorden Corporation; who

bought it from Samuel's son, John Ashton Fielden, for the sum of 10,547 pounds.

Between the wars the house was utilised as a museum, which housed fossils,

butterflies, birds and relics of local prehistory. The Todmorden Historical

Rooms were closed in 1947 because of dry rot, and the house was finally demolished

in 1953. All that remains today is the park and a few of the old mansion's

outbuildings. Part of the site now contains a war memorial and a garden of remembrance.

Centre Vale Park is the scene of an annual summer gala, and the 1984 gala saw

the staging of the Battle of Gettysburg by one of those societies of enthusiasts,

who delight in re-creating great military conflicts of the past. It was a spectacular

event. The smoke of carbines and the roar of cannons could be seen, heard, (and

felt) all over the valley. As I stood there, feeling the ground shaking beneath my feet

as the guns roared, I wondered if anyone had realised the curious relevance of

this event to the real life history of Todmorden; for the cannons of Gettysburg

closed the mills of Todmorden and brought a hardship every bit as great as that

endured by the Confederacy when Sherman began his famous "march to the sea".

From the very outset the whole of Lancashire's textile industry had been

dependent upon an uninterrupted supply of imported raw cotton, and with the

onset of the American Civil War in 1861, and the North's subsequent blockade of the

Confederacy, the supply of cotton from the South began to steadily dry up. This

caused widespread distress in the cotton manufacturing areas of Lancashire. A

wave of speculation on the Liverpool Cotton Exchange made prices soar, and

cotton was even taken from mills to be resold. At the same time the employers

took advantage of the Cotton Famine to force down wages to as little as 4s and 5s a

week. Soon, however, mills had closed down all over Lancashire and jobless

operatives flooded the Unions demanding relief. In 1861 the census population

of the Todmorden Union was 29,727 and the rateable assessment for the poor

rate 89,696 pounds.

In order to help the various Boards of Guardians to cope with the distress the

Union Relief Act was passed in 1862. This gave special powers, by which the

public authorities could at once undertake a programme of public works, making

roads, enlarging reservoirs, and cleaning out river beds. The Fielden brothers

helped by employing men on road mending and making schemes. In connection

with this work there were 3,000 suits of clothing and 300 pairs of watertight

boots distributed. In 1863, when Fieldens were shut down for 9 months the

employees were paid half their usual wages, and were given work cleaning the

machines and reclaiming wastelands. The Todmorden Relief Fund Committee met in

rooms at Dale Street while the Cotton Famine lasted, with John Fielden J.P. as its

chairman. Work was found in other trades, and a sewing school established

where girls could earn 6d a day for a five day week. Cheques to shopkeepers,

payable in provisions or goods, were issued to those in the most urgent need.

All the mills in Todmorden were at a standstill; the only cotton available being

Indian cotton, known as Shurat. This inferior cotton was notorious among cotton

spinners for being 'bad' work. As one Todmorden operative put it, "we were

fit for naught but to goa t't'bed when we'd done wi' it!". Even a generation

later the word 'Shurat' was used in Lancashire as a synonym for 'rubbish'. A verse

from a contemporary ballad, dating from the time of the 'Famine', and written by

Samuel Laycock, who was a power loom weaver of Stalybridge, echoes the

sentiment which must have been felt by the depressed and destitute operatives of

Todmorden:

"Oh dear if yon Yankees could only just see

heaw they're clemmin' an' starvin' poor weavers loike me,

Aw think they'd sooin settle their bother and strive, to send us

some cotton to keep us alive. Come give us a lift, yo' 'at han

owt to give an' help yo'r poor brothers an' sisters to live, be kind

an' be tender to th' needy and poor, an' we'll promise when

t'toimes mend we'll ax yo' no moor . . ."

(Shurat Weaver's Song)

John Fielden's Statue (Terminus Absolute!).

Now, at last, we are approaching the end of the Fielden Trail. By a clump of

rhododendrons, a little path from Carr Laithe meets another path coming up from

the left. Turn sharp left and pass under trees to John Fielden's statue, which stands at

a junction of park paths, near an aviary.

'Honest John's' statue has moved around a bit since it was unveiled at Todmorden on

a blustery April day in 1875. Made by J. H. Foley in 1863, it stood originally by the

western side of the Town Hall until 1890, when it was removed to Fielden Square

and erected outside the present Conservative Club. It was moved to its present

position in Centre Vale Park in 1938, and today there is talk of returning it to