THE

WATERSHEDS WALK

SECTION 3:- Ponden to Keighley

Now we come to the final, and most arduous section of the walk. Section 3 is tough. It leaves the 'beaten track' behind, and from here on, apart from the brief promenade along Earl Crag, it is quite lonely. The boundary walk across Ickornshaw Moor to the Hitching Stone is not only trackless, but potentially dangerous if the weather is bad and you are ill equipped. If the cloud comes down you will need both a compass and a knowledge of how to use it. If in doubt, use a map.

Just beyond Ponden Hall and a thriving hillfarm that was a ruin only a few years ago, the Pennine Way descends to the Colne Road and the Worth above Ponden Reservoir and then climbs up the hillside to Crag Bottom and the Oakworth Road. Here is your last chance to 'get off' if the weather or the dark is closing in.

From here on, a long, tedious ascent (made all the more tedious by a succession of false horizons) leads to the fence on the summit of Ickornshaw Moor near the Wolf Stones. Here the prospect of Lancashire opens up, with cooling towers in Burnley visible, and Pendle Hill dominating the skyline. (The fence is, in fact, the county boundary.)

Ickornshaw has a famous son. Here on this wild upland were scattered the ashes of Viscount Lord Philip Snowden, the first Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was born in nearby Ickornshaw. Snowden had a long and illustrious career. A member of Cowling Parish Council in 1894, he was for 20 years an active ILP member; he became the party's chairman, and, after two unsuccessful attempts, finally entered parliament as M.P. for Blackburn. He died in 1937.

Here, on the summit of Ickornshaw Moor, we bid the Pennine Way farewell. The route now follows the fence on the Yorkshire side to Maw Stones. There is no path here, and certainly no right of way (although I have never been challenged). The going here is, to put it mildly, rough. At Maw Stones the fence veers to the left and you are on your own. Here there is supposedly a public footpath leading in the general direction of the Hitching Stone but find it if you can. If the day is clear it is simpler to follow a beeline across the moor towards the Hitching Stone and the Earl Crag Monuments, which are now visible. (The Stone is in line with the tower). If the cloud is down though, this is where you will have to use your compass, as the moor between here and the Hitching Stone is not only infested with nasty bogholes but is also quite innocent of paths.

Your rest at the Hitching Stone will be well earned. From a distance it looks quite unremarkable, but when you stand beside it you realise that attaining it has been well worth the effort. It is faintly reminiscent of the Calf Rock at Ilkley. If ever there was a place ideally suited to Druidic rituals, this must surely be it. You would not be surprised to find a legend associated with the Hitching Stone, and sure enough, there is one.

The Hitching Stone is 21 feet high and said to weigh about a thousand tons. It stands 1,180 feet above sea level and commands good views which include Pendle, Ingleborough, Penyghent, Buckden Pike, Great Whernside, Simon's Seat and Beamsley Beacon. The rock is also the meeting point of three different moors and also marks the boundary between the ancient wapentakes of Skyrack and Staincliff. According to legend, a 'cunning woman' who lived on the edge of Rombald's Moor took a dislike to this huge boulder which lay in front of her house. Curses had no results, so, in the end, in a fit of anger she seized her broom-stick, inserted it into a hole in the rock and 'hitched' it across the valley to Sutton, where it now stands.

The boulder certainly has some odd characteristics. The top of it is cloven, and a short scramble up the face of the boulder presents rather a surprise, for the cleft contains not, as you might expect, a platform of rock, but a deep 'bath' full of clear rainwater - ideal for a dip on a hot day! The western side of the Hitching Stone is even more curious. A strange recess, high up in the side of the rock, is known as the Priest's Chair. Connected with this, a smooth, round hole runs right through the rock and its sides are curiously patterned in parts. Here must surely be the origin of the Hitching Stone legend. The geological explanation is that the hole was caused by the weathering out of a large fossil tree (Lepidodendron), and if you are carrying a heavy stigmaria in your pocket gleaned from Withins Height you will know what I mean! It does not take a great stretch of the imagination to figure out what our rather less scientific ancestors would have made of this phenomenon: the tree marks were caused by the witch's broomstick when she 'hitched' the stone. Another story says that the markings were caused by the scales of a fossil fish, but even a witches broomstick is more believable than that. There is, by the way, a most excellent display of local fossils in the Cliffe Castle Museum in Keighley, where there is even a life size diorama depicting in a most startling fashion exactly what a carboniferous forest looked like in its prime, complete with prehistoric reptiles.

It might seem surprising, but a fair was once held annually at this bleak spot. It was apparently held in August, but the custom has long since died out. It would seem that the fair was quite an event. It was certainly very partisan, as both Cowling and Sutton kept their stalls within their own boundaries. There was horseracing, footracing, quoits and bizarre contests like 'treacle pudding eating' and seeing how many dry crusts of bread could be eaten after drinking a pint of water!

The Hitching Stone 'racecourse' was marked by boulders on the moor. To the east is the Kidstone and at the terminus of the racecourse the curiously named Navaxstone. The origin of the name is obscure. A 19th century explanation is that the name is a corruption of the Greek 'navarch', meaning 'commander of the fleet', but in view of the antiquity of these stones such an explanation seems unlikely.

It is not wise to jump to conclusions about place names; it is quite possible for ten different authors to give you ten different explanations!

But to get back to the Watersheds Walk: the way on from the Hitching Stone is quite obvious, and after crossing the back lane to Colne, the pinnacle on Earl Crag looms large. The view however, does not open up until you actually climb onto the base of the pinnacle, and suddenly, there before you is the wide expanse of the Aire Valley below Skipton.

The origins of the pinnacles on Earl Crag are obscure. There is in actual fact only one pinnacle, the other monument being a prospect tower. I used to come here as a child and scarmble on the rocks - it was a magic place. The Earl Crag Monuments, theSutton Crag Pinnacles, I am not sure which is correct; local folk always call it Cowling Pinnacle and that's good enough for me.

Wainman's Pinnacle, which is the older of the two monuments, stands in a commanding position on the crag overlooking Carr Head. As I said, its origins are obscure. One theory suggests that it was erected by Lady Amcotts, the young wife of one of the Wainman family, in memory of her husband who fell for the royalist cause during the Civil Wars. A more popular theory however, is that it was erected in 1815 to commemorate Wellington's victory at Waterloo. By the latter part of the 19th century the pinnacle had become severely damaged by lightning, as a result of which it was demolished and rebuilt in January 1900 by Messrs. Gott and Riddiough of Cowling. This is the pinnacle which we see today.

From Wainman's Pinnacle the Watersheds Walk is a fine promenade along the crags to the other monument, Lund's Tower. The views here are excellent. In the valley below can be seen the outline of the Aire valley trunk road, and beyond the main Colne road leading up from Crosshills can be seen the chimney on Cononley Gib, the remains of lead mines. Below sprawls Sutton, Kildwick and all the bustle of traffic on the busy A629. the distant cluster of white buildings down below is the Airedale General Hospital.

Lund's Tower is a child's dream, a fortress to be defended with boiling oil and arrows. The spiral staircase that winds up to its lofty turret is narrow, and adults do not need to be tall in order to bump their heads at the top of the staircase. Lund's Tower (sometimes known somewhat confusingly as Sutton Pinnacle) was built at the instigation of Mr. James Lund of Malsis Hall, but here again we are stuck as to an explanation of why it was actually built. It may have been erected to commemorate the 21st birthday of his daughter Ethel, her death, or alternatively Queen Victoria's Jubilee. No-one really seems sure.

Beyond Lund's Tower the Watersheds Walk takes to the tarmac and follows the road to Slippery Ford. Even though you are on a metalled road, cars are happily few and far between, and, as lapwings wheel and cry overhead, you will feel a splendid sense of isolation.

At Slippery Ford we meet the headwaters of the North Beck which runs all the way down to Keighley and our journey's end. The path here is elusive and ill defined, but as you contour the hillside above the beautiful valley of Newsholme Dene, watching the rabbits scurrying in all directions, you can take comfort in the knowledge that it is (almost) downhill all the way.

There are rabbits aplenty in the upper reaches of Newsholme Dene. The former ravages of myxomatosis have taken their toll, and the disease now seems to be on the wane as the rabbit population gradually develops an immunity to it. The term 'rabbit' is a misnomer. As a leveret is to a hare, so is a rabbit to a coney. Its correct name is coney, and the reason 'rabbit' has become the name of the whole species rather than of just its young is quite simple: generations of butchers have been wont to pass coney off as 'rabbit' in the same way they pass mutton off as 'lamb', and the name has stuck. On the other side of the coin, no self respecting furrier would ever refer to a coney fur coat as 'rabbit'.

At Bottoms Farm, beyond a marshy gully, there is a stile which is quite unaltered since I drove the last nail into it in the spring of 1980. A brief climb up to the road, a favourite haunt of bilberry pickers in summer, and we are once more on our way back down the valley, following an old paved track which leads to the hamlet of Newsholme Dean. Here lived the Shackletons in Elizabeth I's day. One of its members, Roger Shackleton, was Lord Mayor of York in 1693. In the valley below can be seen the Newsholme Dene packhorse bridge, inconspicuous without parapets; this style of bridge, however, was the norm in the days of the packhorses. There is also a clapper bridge of uncertain antiquity beside it. By now, you should be shattered, so if you hear the jingle of packhorse bells, and the shouts of the brogger urging his jagger ponies up the slope, you would be well advised to sit down and rest your weary brain.

The next port of call on the Watersheds Walk is Goose Eye. By now the evening will be closing in and the Turkey Inn will probably be open. Here is the place to briefly halt and enjoy not only a good, but also a highly unusual pint!

Goose Eye is as picturesque as its name. It was, in fact, an industrial hamlet, centred on what were formerly its two worsted mills and its paper manufactory. The paper was made at Turkey Mill, owned in the last century by Messrs. J. Town and Sons, who employed most of Goose Eye's population. Besides paper, Goose Eye was also famous for its innkeeper, who was renowned as one of the greatest 'fat men' of his time. Apparently he drew the scale at 24st. 10lb and was six feet two inches in height. By his death in 1879 at the age of 38 he had, however, been reduced to a gaunt skeleton of a man. There must be a moral in there somewhere. Perhaps he'd been walking the Watersheds Walk!

Today Goose Eye's main assets are its hotel and its brewery. This is what I meant when I said that your pint will be unusual, as the Turkey brews its own beer, and in doing so hearkens back to an earlier age, when pubs brewing their own beer were the norm rather than the exception. Two brews are available: Goose Eye Bitter and the rather more volatile Old Three Laps. Herein lies a tale. The beer is so named not because (as an associate once said) "two pints and you'll do three laps of the pub!" No, the story is rather more interesting than that, for the name is a memorial to the life and times of a rather eccentric gentleman by the name of William Sharp.

William Sharp was the son of a small farmer and weaver, who in the early 19th century (before the advent of the factories) produced worsted cloth to be sold at the Halifax Piece Hall. It is said that his father was so miserly that when he called in a tailor to get a suit made, the amount of cloth he provided was inadequate for the task. The tailor pointed out that if he could not supply any more cloth then the coat would only have three laps(coat tails)."Then mek it wi' three laps anyrooad," stuttered young William. Thus it was that the coat was so made, and William Sharp acquired the nickname of 'Old Three Laps.'

This, however, was not William's main claim to fame. William was a bit of a loner. He walked the moors with his gun and often spent whole nights out in the open air. Eventually he bought Whorls, a farmstead high on the moors beyond Laycock, not far from Keighley Tarn. Then, at the tender age of thirty, Bill Sharp fell in love. The object of William's ardent attentions was one Mary Smith, who lived at Bottoms in Newsholme Dene (through which we have just passed). They enjoyed a long courtship and eventually William obtained consent to marry her, although this might have had something to do with the little baby which had suddenly appeared at Bottoms. The wedding day was fixed and everything seemed rosy, until William's miserly father fell out with the bride's father over the dowry. The result of this was that, on the wedding day, the bride was kept at home by her disapproving father and poor William was left at the altar. In the words of Keighley, the historian, "the great slip between the cup and the lip preyed heavily on the susceptible mind of the ardent lover." It was 1807. Heartbroken, poor William went home and went to bed. He stayed there until his death in 1856!

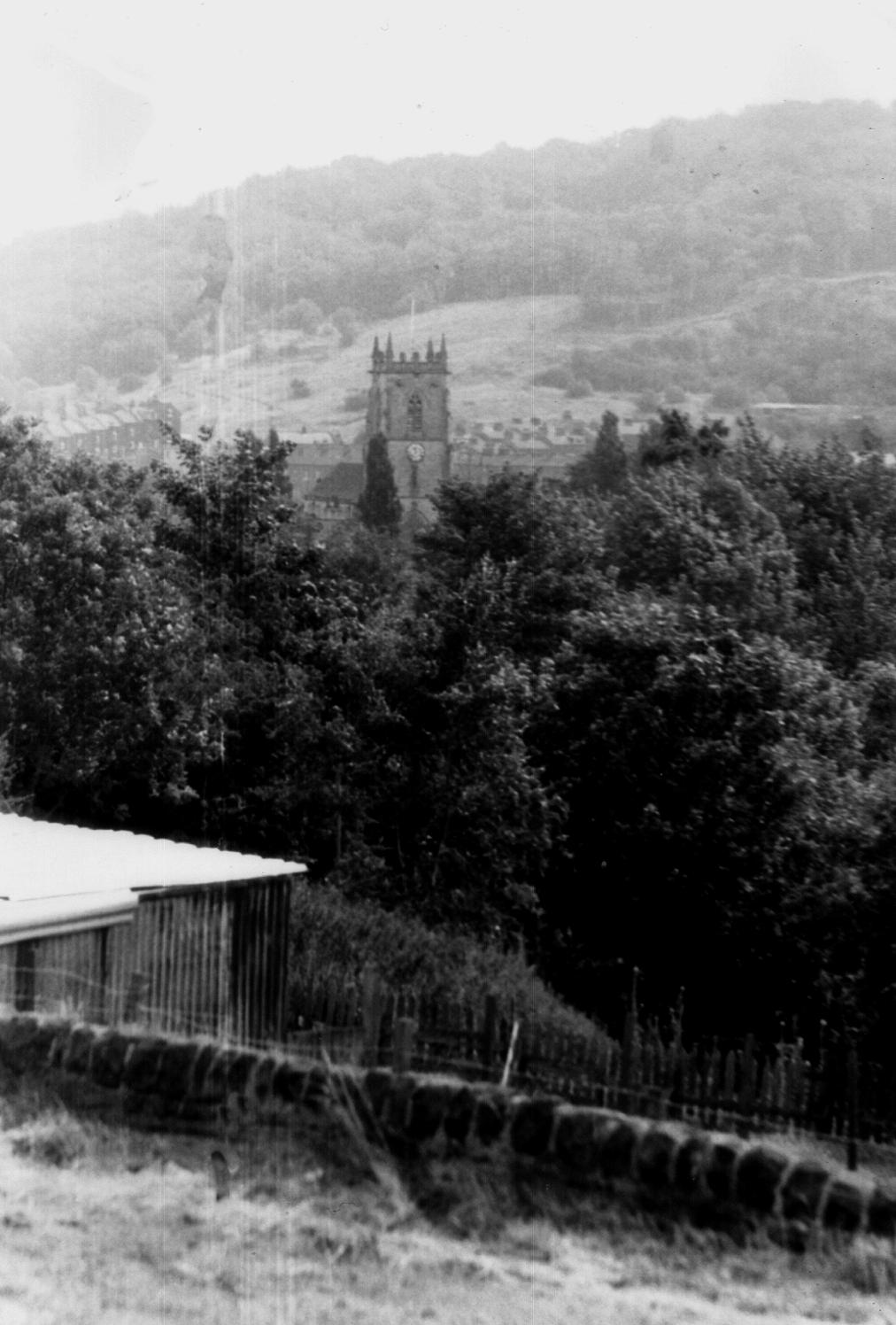

'Old Three Laps' lay in a plain four poster bed for 49 years, and his window was not opened for 38 years. He refused to speak to anyone, and in the course of time his legs became contracted towards his body. He died on March 3rd 1856. His last words were "Poor Bill, poor Bill Sharp!", the first articulate words he had uttered for years. He was buried at Keighley Churchyard, where his coffin was so large it excited a great deal of attention: the weight of the coffin and corpse was estimated at 480 lbs, and apparently required 8 men to lower it into the grave. In such a public and undignified manner did 'Old Three Laps' take his leave of this world!

From Goose Eye the Watersheds Walk climbs out of Newsholme Dene up to Laycock, where, after a brief excursion through the village, it promptly descends back into the valley from whence it came. This climb up to Laycock is the last uphill climb before Keighley.

Laycock is a pretty little village, and if the pub at Goose Eye is closed, and the Post Office at Laycock open, then this is the spot to secure much needed refreshment.

Laycock is an ancient place: Domesday informs us that in William the Conquerors' time "Ravensuar had two carucates of land to be taxed in the (then) Manor of Lacoc," a carucate being the amount of land which could be ploughed in one day using a team of oxen (roughly 120 acres). At one time this little village, straggling its narrow and no doubt venerable road, was considered to be of equal importance to Keighley. Maypole celebrations were still held annually at Laycock, but Keighley and the Industrial Revolution passed it by long ago, and it now remains, pretty and picturesque, but quite obscure.

From Laycock the Watersheds Walk descends to Wood Mill and Holme House Woods, and from here on the route is a pleasant woodland ramble by the beck, virtually all the way to Keighley. This must be, in fact, the 'Royal' road to Keighley, for the town hardly betrays its presence until you enter the main Oakworth Road at the very end of our journey. The effect is really quite surprising, and quite contrary to expectations.

The valley of the North Beck has not always, however, been so peaceful. Dr. Whitaker, the antiquarian Vicar of Whalley, writing at the beginning of the nineteenth century describes it thus:

"Before the introduction of the manufactures, the Parish of Keighley did not want its retired glens and well wooded hills; but the clear mountain torrent is now defiled, its scaly inhabitants suffocated by filth; its murmers lost in the din of machinery; and the native music in its overhanging groves exchanged for oaths and curses......."

The Industrial Revolution had, indeed arrived with a vengeance, for the North Beck (it was then known as the Laycock Beck) had become virtually lined with mills by the end of the nineteenth century. Newsholme Higher and Lower Mills, Goose Eye, Wood Mill, Holme House and Holme Mill, Castle Mill and North Brook Mill (belonging to the Hattersleys) all contributed to the general pollution and disruption of the North Beck. Mercifully, the water is now clean once more and the effects of the Industrial Revolution have receded. As the evening sunlight slants through the trees and the midges swarm over the beck, you can marvel that you can be so remote from, and yet so near to, the bustling urban clamour of Keighley.

The woods around the North Beck are the largest woodland areas so far encountered on our journey, which has largely been confined to the moorlands. The woods, especially downstream of Goose Eye, are quite mature, and are almost wholly deciduous, containing a variety of trees, of which oaks and birches seem to be the most predominant. Now that the mills have gone, the dams and sluices have become redundant, and nature has taken back that which our enterprising ancestors stole from it. The landscape of the hills changes with the passing of the seasons, but nowhere is this seasonal progress more noticeable than here in the woods where we may trace the passing of the seasons by observing the steady development of the woodland habitat throughout the year. In January or February we can see little. The woodland floor slumbers fitfully beneath its cold winter blanket, robins haunt the holly trees and the occasional fox scavenges in the snow. March and April sees the Beck regularly in spate, its raging, icy waters flooding meadows and dragging down debris from upstream. Spring is heralded by the appearance of the lesser celandine (Ranunculus Ficaria) whose small, yellow flowers and spear shaped leaves form a yellow carpet all over the banks of the stream. It is a relative of the buttercup, and, like the buttercup is poisonous, its sap once being used to poison the tips of arrowheads (or so I am informed). It is often seen in the company of its close relative, the wood anemone (Anemone Nemorosa) or windflower, whose delicate white flower is also buttercup like. As with most members of the buttercup family, these plants contain the poisonous alkaloid protoanemonin, which can cause blisters and intestinal inflammation if eaten. These plants herald spring, and by the time the sap rises and the trees come into leaf, these flowers, only recently so numerous, are gone.

April and May is a time of rapid change. The trees come into leaf and the bluebells arrive in great numbers. Linnaeus classified the bluebell as 'Hyacinthus Non Scriptus' because there was no 'writing' on the petals of the flowers; on true hyacinths the marks on the petals form the greek letters A I, meaning 'alas!' This was said to be the dying cry of the youth Hyacinthus who was killed while sporting with Apollo who, out of pity, turned him into a flower. Sometimes you will find odd groups of bluebells that are white rather than blue.

Late spring also brings other species. The bistort (Polygonum Bistorta) appears at this time, along with the young nettles, both of which are used in the preparation of Calderdale Dock Pudding. In the woods we now see the red campion (Silene Dioica), which is very common, and the ramsons, or wild garlic, (Allium Ursinum) with its highly distinctive smell and delicate white flower. Now the insect life begins to stir and ants and bees become numerous, not to mention midges.

Early summer sees the complete unfurling of what the woodlands have to offer. Herb roberts and pink purslanes grow by the beck, along with the woodland forget-me-nots and the speedwells. Most dominant of all are those alien species which seem to choke everything: the himalayan balsam (policemans helmets) with its distinctive purple flowers and wet, weak celery like stalks; the butterbur with its rank, rhubarb like leaves, and of course the ubiquitous rosebay willow herb (Epilobium Augustifolium), all of which grow in large colonies. Also to be seen are the foxgloves (Digitalis Purpurea), with their unmistakeable clusters of purple bells, and the deep bracken, the stems of which can slice a grasping hand with the ease of a razor blade. The 'scrolls' on bracken plants can be eaten and have a pleasant almond flavour. You would be wise not to overdo it though - the plants' oil tastes of almonds because it contains a natural form of cyanide!

Midsummer into autumn sees the arrival of the fungi. The types and distribution of fungi can vary from year to year. A species abundant one year can be completely absent the next year, and replaced by one that has not been seen for a long time. Of course, if we consider the true nature of fungi such vagaries are hardly surprising. The 'toadstool' we see on the woodland floor is not the whole plant, merely its 'flower' or fruiting body. The actual fungus itself consists of a mycelium, a network of microscopic threads (hyphae) which grow out radially from a central spore and form a constantly branching underground network. The main fungus then is microscopic, so distribution of fruiting bodies on the surface is no guide at all to what is in the ground - hence the apparent unpredictability.

The most common fungus to be found in deciduous woodlands is the species known as Russula. Some have yellow caps, some reddish, but all are easily distinguishable by their pure white, waxy flesh which crumbles very easily. Some of these are edible, but the only sure way is to taste them and the inedible russula, the sickener (Russula Emetica), will make its identity known to you in no uncertain manner should you have the misfortune to taste one. More promising to the would-be gourmet are the genus of tubed fungi known as Boletaceae. It is a safe rule-of-thumb to say that all members of this family are non-poisonous. (The only poisonous bolete, Boletas Satanas or Devils Bolete is quite rare in the North of England, and never fatal if eaten). The boletes are quite easy to spot on account of their sponge-like tubes. Most common of all is the rough stemmed birch bolete with its rough 'woody' stem which turns blue when handled and orange cap, which grows around the roots of birch trees. (It is the chief ingredient of Austrian Mushroom Soup). Other tasty boletes are the bay and 'penny bun' boletes, but these are less common.

Now we move on to the poisonous species, most common of which is the panther cap (Amanita Pantherina). The death cap and the pure white destroying angel are mercifully less common, but anybody picking gill cap fungi with a view to eating them should be able to identify these potential killers. Another common, and poisonous fungus is the earth ball (scleroderma). This is found on acid, peaty banks, looks rather like a potato, and in old specimens you are liable to be powdered with black dust. The earth ball is lime hating and thus likes deep, acid soil, which is why it is so common in these Pennine woodlands and absent from the limestone areas of Craven.

These are some of the woodland species of fungi you are most likely to encounter, but the list is by no means exhaustive and a good guide to fungi can provide hours of fascination in these autumn woods.

The mushroom season takes us through autumn into winter. Autumn is a time of fallen leaves and woodsmoke, as the squirrels prepare for winter. The red squirrel is less common now, and is more likely to be found in coniferous woodlands, where it has not been supplanted by its more common American neighbour, the grey squirrel (Squirius Carolinensis), which is rife in the deciduous woods of the Pennine valleys. And so we come to winter, and we await the arrival of spring, when the process starts all over again.

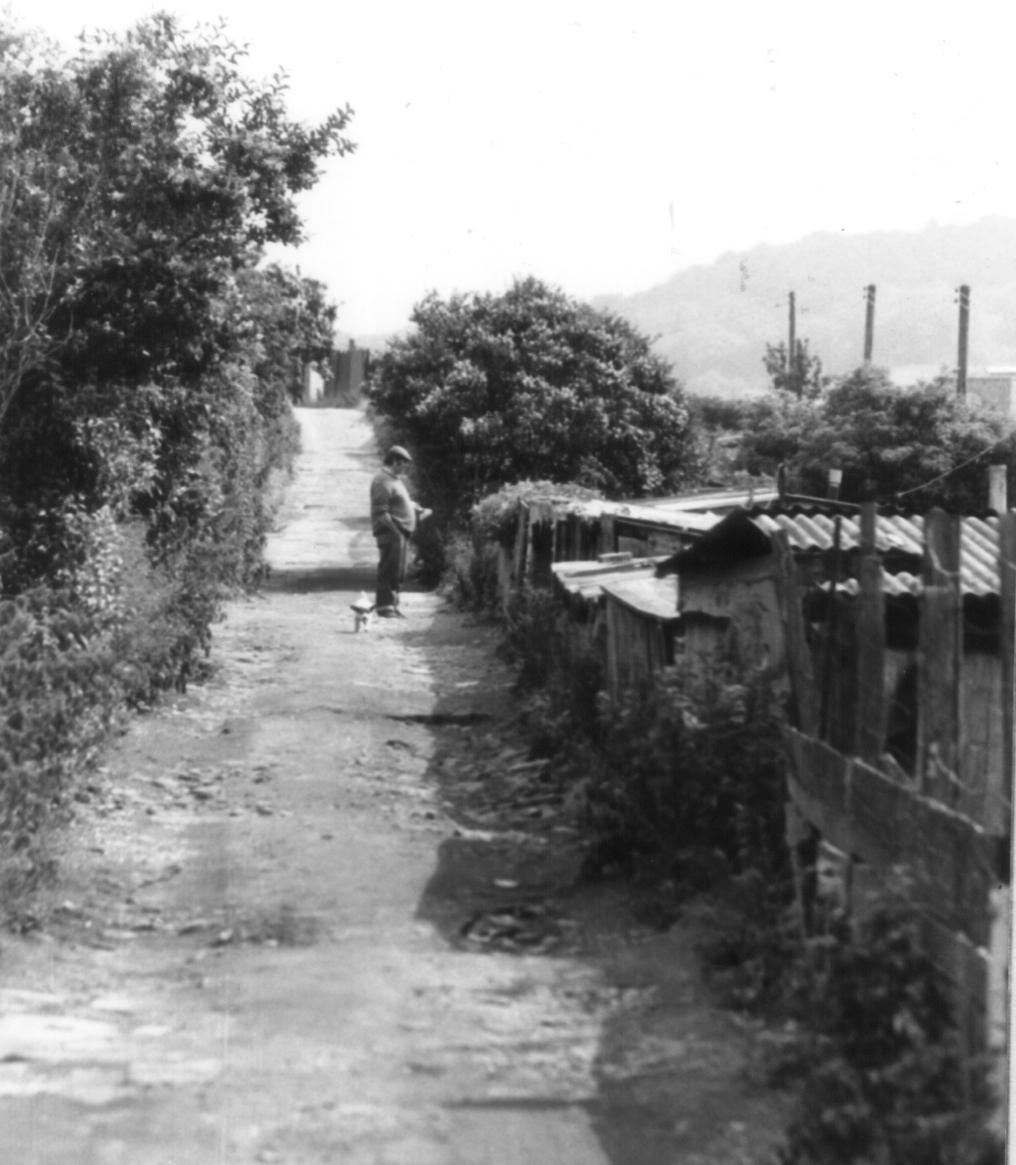

Beyond Holme Mills (Stells Paper Tubes) the route leaves the woodlands, and after a slight ascent from the beck enters a track which contours the hillside, leading through a ricketty labyrinth of urban allotments. This place has a rough fascination which is entirely its own. Behind motley fences and tumbledown shacks and sheds, hens scrat, geese waddle, and pigmuck festers among the potatoes and runner beans. The allotments seem to be populated by rough-cut men and yapping Jack Russell terriers. (Besides me and mine!). These allotments seem to be 'home' for some of these men; perhaps the more henpecked ones actually sleep here, for the whole hillside seems to be a virtual 'shanty town', which would not look out of place on the outskirts of some third world metropolis like Rio De Janeiro or Hong Kong.

Soon the allotments give way to a cobbled road, beyond which a descending snicket leads once more to the beckside, where the beck, rather unobligingly, disappears underground beneath the main Oakworth Road. Where the snicket emerges into the Oakworth Road, hard by the parked mailvans of the Oakworth Road Sorting Office, is the end of Section 3, and also the end of our Watersheds Walk. If you parked your car nearby, you will find that relief is 'nobbut a cockstride away'. If, however, you came on the bus or train you will have to walk right across Keighley Town Centre. The longest hobble is back to the railway station, but if you did come by train you will at least enjoy the dubious satisfaction of arriving back at the start of Section 1.!

Well, you have now completed the Watersheds Walk, and I sincerely hope you enjoyed walking it as much as I did. Rambling is not only an exercise for the legs, it is also a tonic for the imagination - especially if, like me, you prefer to travel alone. The babbling becks, the wooded valleys, the bleak uplands with their embattled stone farmhouses and barns... all are peopled with their own peculiar kinds of ghosts. As the deep silence sighs deafeningly across the moorlands and the lapwings circle over the rough, boggy pastures, it is not difficult for the imagination to flit from one world to another, from times present to times past, and even (with uncertainty) to times yet to come.

Silence must be sought - the 20th century does not deliver it to your door. In the silences you will find your hopes, your dreams, aspirations and above all the quality of life. On an arduous journey on foot, through wild, lonely landscapes you will find a microcosm of all the triumphs and successes, failures and pitfalls, that you must enjoy or endure as part and parcel of your day-to-day existence. These reasons alone make a journey like the Watersheds Walk well worth the effort, for, as you find your way around the Worth Valley, you will also find yourself.

Copyright Jim Jarratt.

2006 First Published by Smith Settle 1989

Now we come to the final, and most arduous section of the walk. Section 3 is tough. It leaves the 'beaten track' behind, and from here on, apart from the brief promenade along Earl Crag, it is quite lonely. The boundary walk across Ickornshaw Moor to the Hitching Stone is not only trackless, but potentially dangerous if the weather is bad and you are ill equipped. If the cloud comes down you will need both a compass and a knowledge of how to use it. If in doubt, use a map.

Just beyond Ponden Hall and a thriving hillfarm that was a ruin only a few years ago, the Pennine Way descends to the Colne Road and the Worth above Ponden Reservoir and then climbs up the hillside to Crag Bottom and the Oakworth Road. Here is your last chance to 'get off' if the weather or the dark is closing in.

From here on, a long, tedious ascent (made all the more tedious by a succession of false horizons) leads to the fence on the summit of Ickornshaw Moor near the Wolf Stones. Here the prospect of Lancashire opens up, with cooling towers in Burnley visible, and Pendle Hill dominating the skyline. (The fence is, in fact, the county boundary.)

Ickornshaw has a famous son. Here on this wild upland were scattered the ashes of Viscount Lord Philip Snowden, the first Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was born in nearby Ickornshaw. Snowden had a long and illustrious career. A member of Cowling Parish Council in 1894, he was for 20 years an active ILP member; he became the party's chairman, and, after two unsuccessful attempts, finally entered parliament as M.P. for Blackburn. He died in 1937.

Your rest at the Hitching Stone will be well earned. From a distance it looks quite unremarkable, but when you stand beside it you realise that attaining it has been well worth the effort. It is faintly reminiscent of the Calf Rock at Ilkley. If ever there was a place ideally suited to Druidic rituals, this must surely be it. You would not be surprised to find a legend associated with the Hitching Stone, and sure enough, there is one.

The boulder certainly has some odd characteristics. The top of it is cloven, and a short scramble up the face of the boulder presents rather a surprise, for the cleft contains not, as you might expect, a platform of rock, but a deep 'bath' full of clear rainwater - ideal for a dip on a hot day! The western side of the Hitching Stone is even more curious. A strange recess, high up in the side of the rock, is known as the Priest's Chair. Connected with this, a smooth, round hole runs right through the rock and its sides are curiously patterned in parts. Here must surely be the origin of the Hitching Stone legend. The geological explanation is that the hole was caused by the weathering out of a large fossil tree (Lepidodendron), and if you are carrying a heavy stigmaria in your pocket gleaned from Withins Height you will know what I mean! It does not take a great stretch of the imagination to figure out what our rather less scientific ancestors would have made of this phenomenon: the tree marks were caused by the witch's broomstick when she 'hitched' the stone. Another story says that the markings were caused by the scales of a fossil fish, but even a witches broomstick is more believable than that. There is, by the way, a most excellent display of local fossils in the Cliffe Castle Museum in Keighley, where there is even a life size diorama depicting in a most startling fashion exactly what a carboniferous forest looked like in its prime, complete with prehistoric reptiles.

It might seem surprising, but a fair was once held annually at this bleak spot. It was apparently held in August, but the custom has long since died out. It would seem that the fair was quite an event. It was certainly very partisan, as both Cowling and Sutton kept their stalls within their own boundaries. There was horseracing, footracing, quoits and bizarre contests like 'treacle pudding eating' and seeing how many dry crusts of bread could be eaten after drinking a pint of water!

The Hitching Stone 'racecourse' was marked by boulders on the moor. To the east is the Kidstone and at the terminus of the racecourse the curiously named Navaxstone. The origin of the name is obscure. A 19th century explanation is that the name is a corruption of the Greek 'navarch', meaning 'commander of the fleet', but in view of the antiquity of these stones such an explanation seems unlikely. It is not wise to jump to conclusions about place names; it is quite possible for ten different authors to give you ten different explanations!

But to get back to the Watersheds Walk: the way on from the Hitching Stone is quite obvious, and after crossing the back lane to Colne, the pinnacle on Earl Crag looms large. The view however, does not open up until you actually climb onto the base of the pinnacle, and suddenly, there before you is the wide expanse of the Aire Valley below Skipton.

The origins of the pinnacles on Earl Crag are obscure. There is in actual fact only one pinnacle, the other monument being a prospect tower. I used to come here as a child and scarmble on the rocks - it was a magic place. The Earl Crag Monuments, theSutton Crag Pinnacles, I am not sure which is correct; local folk always call it Cowling Pinnacle and that's good enough for me.

From Wainman's Pinnacle the Watersheds Walk is a fine promenade along the crags to the other monument, Lund's Tower. The views here are excellent. In the valley below can be seen the outline of the Aire valley trunk road, and beyond the main Colne road leading up from Crosshills can be seen the chimney on Cononley Gib, the remains of lead mines. Below sprawls Sutton, Kildwick and all the bustle of traffic on the busy A629. the distant cluster of white buildings down below is the Airedale General Hospital.

Beyond Lund's Tower the Watersheds Walk takes to the tarmac and follows the road to Slippery Ford. Even though you are on a metalled road, cars are happily few and far between, and, as lapwings wheel and cry overhead, you will feel a splendid sense of isolation.

At Slippery Ford we meet the headwaters of the North Beck which runs all the way down to Keighley and our journey's end. The path here is elusive and ill defined, but as you contour the hillside above the beautiful valley of Newsholme Dene, watching the rabbits scurrying in all directions, you can take comfort in the knowledge that it is (almost) downhill all the way.

There are rabbits aplenty in the upper reaches of Newsholme Dene. The former ravages of myxomatosis have taken their toll, and the disease now seems to be on the wane as the rabbit population gradually develops an immunity to it. The term 'rabbit' is a misnomer. As a leveret is to a hare, so is a rabbit to a coney. Its correct name is coney, and the reason 'rabbit' has become the name of the whole species rather than of just its young is quite simple: generations of butchers have been wont to pass coney off as 'rabbit' in the same way they pass mutton off as 'lamb', and the name has stuck. On the other side of the coin, no self respecting furrier would ever refer to a coney fur coat as 'rabbit'.

At Bottoms Farm, beyond a marshy gully, there is a stile which is quite unaltered since I drove the last nail into it in the spring of 1980. A brief climb up to the road, a favourite haunt of bilberry pickers in summer, and we are once more on our way back down the valley, following an old paved track which leads to the hamlet of Newsholme Dean. Here lived the Shackletons in Elizabeth I's day. One of its members, Roger Shackleton, was Lord Mayor of York in 1693. In the valley below can be seen the Newsholme Dene packhorse bridge, inconspicuous without parapets; this style of bridge, however, was the norm in the days of the packhorses. There is also a clapper bridge of uncertain antiquity beside it. By now, you should be shattered, so if you hear the jingle of packhorse bells, and the shouts of the brogger urging his jagger ponies up the slope, you would be well advised to sit down and rest your weary brain.

The next port of call on the Watersheds Walk is Goose Eye. By now the evening will be closing in and the Turkey Inn will probably be open. Here is the place to briefly halt and enjoy not only a good, but also a highly unusual pint!

Goose Eye is as picturesque as its name. It was, in fact, an industrial hamlet, centred on what were formerly its two worsted mills and its paper manufactory. The paper was made at Turkey Mill, owned in the last century by Messrs. J. Town and Sons, who employed most of Goose Eye's population. Besides paper, Goose Eye was also famous for its innkeeper, who was renowned as one of the greatest 'fat men' of his time. Apparently he drew the scale at 24st. 10lb and was six feet two inches in height. By his death in 1879 at the age of 38 he had, however, been reduced to a gaunt skeleton of a man. There must be a moral in there somewhere. Perhaps he'd been walking the Watersheds Walk!

William Sharp was the son of a small farmer and weaver, who in the early 19th century (before the advent of the factories) produced worsted cloth to be sold at the Halifax Piece Hall. It is said that his father was so miserly that when he called in a tailor to get a suit made, the amount of cloth he provided was inadequate for the task. The tailor pointed out that if he could not supply any more cloth then the coat would only have three laps(coat tails)."Then mek it wi' three laps anyrooad," stuttered young William. Thus it was that the coat was so made, and William Sharp acquired the nickname of 'Old Three Laps.'

This, however, was not William's main claim to fame. William was a bit of a loner. He walked the moors with his gun and often spent whole nights out in the open air. Eventually he bought Whorls, a farmstead high on the moors beyond Laycock, not far from Keighley Tarn. Then, at the tender age of thirty, Bill Sharp fell in love. The object of William's ardent attentions was one Mary Smith, who lived at Bottoms in Newsholme Dene (through which we have just passed). They enjoyed a long courtship and eventually William obtained consent to marry her, although this might have had something to do with the little baby which had suddenly appeared at Bottoms. The wedding day was fixed and everything seemed rosy, until William's miserly father fell out with the bride's father over the dowry. The result of this was that, on the wedding day, the bride was kept at home by her disapproving father and poor William was left at the altar. In the words of Keighley, the historian, "the great slip between the cup and the lip preyed heavily on the susceptible mind of the ardent lover." It was 1807. Heartbroken, poor William went home and went to bed. He stayed there until his death in 1856!

'Old Three Laps' lay in a plain four poster bed for 49 years, and his window was not opened for 38 years. He refused to speak to anyone, and in the course of time his legs became contracted towards his body. He died on March 3rd 1856. His last words were "Poor Bill, poor Bill Sharp!", the first articulate words he had uttered for years. He was buried at Keighley Churchyard, where his coffin was so large it excited a great deal of attention: the weight of the coffin and corpse was estimated at 480 lbs, and apparently required 8 men to lower it into the grave. In such a public and undignified manner did 'Old Three Laps' take his leave of this world!

From Goose Eye the Watersheds Walk climbs out of Newsholme Dene up to Laycock, where, after a brief excursion through the village, it promptly descends back into the valley from whence it came. This climb up to Laycock is the last uphill climb before Keighley.

Laycock is a pretty little village, and if the pub at Goose Eye is closed, and the Post Office at Laycock open, then this is the spot to secure much needed refreshment.

Laycock is an ancient place: Domesday informs us that in William the Conquerors' time "Ravensuar had two carucates of land to be taxed in the (then) Manor of Lacoc," a carucate being the amount of land which could be ploughed in one day using a team of oxen (roughly 120 acres). At one time this little village, straggling its narrow and no doubt venerable road, was considered to be of equal importance to Keighley. Maypole celebrations were still held annually at Laycock, but Keighley and the Industrial Revolution passed it by long ago, and it now remains, pretty and picturesque, but quite obscure.

From Laycock the Watersheds Walk descends to Wood Mill and Holme House Woods, and from here on the route is a pleasant woodland ramble by the beck, virtually all the way to Keighley. This must be, in fact, the 'Royal' road to Keighley, for the town hardly betrays its presence until you enter the main Oakworth Road at the very end of our journey. The effect is really quite surprising, and quite contrary to expectations.

The valley of the North Beck has not always, however, been so peaceful. Dr. Whitaker, the antiquarian Vicar of Whalley, writing at the beginning of the nineteenth century describes it thus:

"Before the introduction of the manufactures, the Parish of Keighley did not want its retired glens and well wooded hills; but the clear mountain torrent is now defiled, its scaly inhabitants suffocated by filth; its murmers lost in the din of machinery; and the native music in its overhanging groves exchanged for oaths and curses......."

The Industrial Revolution had, indeed arrived with a vengeance, for the North Beck (it was then known as the Laycock Beck) had become virtually lined with mills by the end of the nineteenth century. Newsholme Higher and Lower Mills, Goose Eye, Wood Mill, Holme House and Holme Mill, Castle Mill and North Brook Mill (belonging to the Hattersleys) all contributed to the general pollution and disruption of the North Beck. Mercifully, the water is now clean once more and the effects of the Industrial Revolution have receded. As the evening sunlight slants through the trees and the midges swarm over the beck, you can marvel that you can be so remote from, and yet so near to, the bustling urban clamour of Keighley.

The woods around the North Beck are the largest woodland areas so far encountered on our journey, which has largely been confined to the moorlands. The woods, especially downstream of Goose Eye, are quite mature, and are almost wholly deciduous, containing a variety of trees, of which oaks and birches seem to be the most predominant. Now that the mills have gone, the dams and sluices have become redundant, and nature has taken back that which our enterprising ancestors stole from it. The landscape of the hills changes with the passing of the seasons, but nowhere is this seasonal progress more noticeable than here in the woods where we may trace the passing of the seasons by observing the steady development of the woodland habitat throughout the year. In January or February we can see little. The woodland floor slumbers fitfully beneath its cold winter blanket, robins haunt the holly trees and the occasional fox scavenges in the snow. March and April sees the Beck regularly in spate, its raging, icy waters flooding meadows and dragging down debris from upstream. Spring is heralded by the appearance of the lesser celandine (Ranunculus Ficaria) whose small, yellow flowers and spear shaped leaves form a yellow carpet all over the banks of the stream. It is a relative of the buttercup, and, like the buttercup is poisonous, its sap once being used to poison the tips of arrowheads (or so I am informed). It is often seen in the company of its close relative, the wood anemone (Anemone Nemorosa) or windflower, whose delicate white flower is also buttercup like. As with most members of the buttercup family, these plants contain the poisonous alkaloid protoanemonin, which can cause blisters and intestinal inflammation if eaten. These plants herald spring, and by the time the sap rises and the trees come into leaf, these flowers, only recently so numerous, are gone.

April and May is a time of rapid change. The trees come into leaf and the bluebells arrive in great numbers. Linnaeus classified the bluebell as 'Hyacinthus Non Scriptus' because there was no 'writing' on the petals of the flowers; on true hyacinths the marks on the petals form the greek letters A I, meaning 'alas!' This was said to be the dying cry of the youth Hyacinthus who was killed while sporting with Apollo who, out of pity, turned him into a flower. Sometimes you will find odd groups of bluebells that are white rather than blue.

Late spring also brings other species. The bistort (Polygonum Bistorta) appears at this time, along with the young nettles, both of which are used in the preparation of Calderdale Dock Pudding. In the woods we now see the red campion (Silene Dioica), which is very common, and the ramsons, or wild garlic, (Allium Ursinum) with its highly distinctive smell and delicate white flower. Now the insect life begins to stir and ants and bees become numerous, not to mention midges.

Early summer sees the complete unfurling of what the woodlands have to offer. Herb roberts and pink purslanes grow by the beck, along with the woodland forget-me-nots and the speedwells. Most dominant of all are those alien species which seem to choke everything: the himalayan balsam (policemans helmets) with its distinctive purple flowers and wet, weak celery like stalks; the butterbur with its rank, rhubarb like leaves, and of course the ubiquitous rosebay willow herb (Epilobium Augustifolium), all of which grow in large colonies. Also to be seen are the foxgloves (Digitalis Purpurea), with their unmistakeable clusters of purple bells, and the deep bracken, the stems of which can slice a grasping hand with the ease of a razor blade. The 'scrolls' on bracken plants can be eaten and have a pleasant almond flavour. You would be wise not to overdo it though - the plants' oil tastes of almonds because it contains a natural form of cyanide!

Midsummer into autumn sees the arrival of the fungi. The types and distribution of fungi can vary from year to year. A species abundant one year can be completely absent the next year, and replaced by one that has not been seen for a long time. Of course, if we consider the true nature of fungi such vagaries are hardly surprising. The 'toadstool' we see on the woodland floor is not the whole plant, merely its 'flower' or fruiting body. The actual fungus itself consists of a mycelium, a network of microscopic threads (hyphae) which grow out radially from a central spore and form a constantly branching underground network. The main fungus then is microscopic, so distribution of fruiting bodies on the surface is no guide at all to what is in the ground - hence the apparent unpredictability.

The most common fungus to be found in deciduous woodlands is the species known as Russula. Some have yellow caps, some reddish, but all are easily distinguishable by their pure white, waxy flesh which crumbles very easily. Some of these are edible, but the only sure way is to taste them and the inedible russula, the sickener (Russula Emetica), will make its identity known to you in no uncertain manner should you have the misfortune to taste one. More promising to the would-be gourmet are the genus of tubed fungi known as Boletaceae. It is a safe rule-of-thumb to say that all members of this family are non-poisonous. (The only poisonous bolete, Boletas Satanas or Devils Bolete is quite rare in the North of England, and never fatal if eaten). The boletes are quite easy to spot on account of their sponge-like tubes. Most common of all is the rough stemmed birch bolete with its rough 'woody' stem which turns blue when handled and orange cap, which grows around the roots of birch trees. (It is the chief ingredient of Austrian Mushroom Soup). Other tasty boletes are the bay and 'penny bun' boletes, but these are less common.

Now we move on to the poisonous species, most common of which is the panther cap (Amanita Pantherina). The death cap and the pure white destroying angel are mercifully less common, but anybody picking gill cap fungi with a view to eating them should be able to identify these potential killers. Another common, and poisonous fungus is the earth ball (scleroderma). This is found on acid, peaty banks, looks rather like a potato, and in old specimens you are liable to be powdered with black dust. The earth ball is lime hating and thus likes deep, acid soil, which is why it is so common in these Pennine woodlands and absent from the limestone areas of Craven.

These are some of the woodland species of fungi you are most likely to encounter, but the list is by no means exhaustive and a good guide to fungi can provide hours of fascination in these autumn woods.

The mushroom season takes us through autumn into winter. Autumn is a time of fallen leaves and woodsmoke, as the squirrels prepare for winter. The red squirrel is less common now, and is more likely to be found in coniferous woodlands, where it has not been supplanted by its more common American neighbour, the grey squirrel (Squirius Carolinensis), which is rife in the deciduous woods of the Pennine valleys. And so we come to winter, and we await the arrival of spring, when the process starts all over again.

Beyond Holme Mills (Stells Paper Tubes) the route leaves the woodlands, and after a slight ascent from the beck enters a track which contours the hillside, leading through a ricketty labyrinth of urban allotments. This place has a rough fascination which is entirely its own. Behind motley fences and tumbledown shacks and sheds, hens scrat, geese waddle, and pigmuck festers among the potatoes and runner beans. The allotments seem to be populated by rough-cut men and yapping Jack Russell terriers. (Besides me and mine!). These allotments seem to be 'home' for some of these men; perhaps the more henpecked ones actually sleep here, for the whole hillside seems to be a virtual 'shanty town', which would not look out of place on the outskirts of some third world metropolis like Rio De Janeiro or Hong Kong.

Well, you have now completed the Watersheds Walk, and I sincerely hope you enjoyed walking it as much as I did. Rambling is not only an exercise for the legs, it is also a tonic for the imagination - especially if, like me, you prefer to travel alone. The babbling becks, the wooded valleys, the bleak uplands with their embattled stone farmhouses and barns... all are peopled with their own peculiar kinds of ghosts. As the deep silence sighs deafeningly across the moorlands and the lapwings circle over the rough, boggy pastures, it is not difficult for the imagination to flit from one world to another, from times present to times past, and even (with uncertainty) to times yet to come.

Silence must be sought - the 20th century does not deliver it to your door. In the silences you will find your hopes, your dreams, aspirations and above all the quality of life. On an arduous journey on foot, through wild, lonely landscapes you will find a microcosm of all the triumphs and successes, failures and pitfalls, that you must enjoy or endure as part and parcel of your day-to-day existence. These reasons alone make a journey like the Watersheds Walk well worth the effort, for, as you find your way around the Worth Valley, you will also find yourself.