13. THE HACKFALL FOLLIES

Remote, neglected and indescribably peaceful, where the Ure flows through a rocky gorge surrounded by dense overgrown woodlands, this walk features a pleasant village, fine views across to the Cleveland Hills, river scenery and three very important (yet little known) follies.

Getting there: From Pateley Bridge follow B6265 towards Ripon and turn off left, following unclassified road to Kirkby Malzeard. From Kirkby Malzeard follow signs to Grewelthorpe. From Ripon leave by Pateley Bridge road and first turning off to R leads directly to Grewelthorpe. Steep crags, and (in summer) dense undergrowth, make this walk not really suitable for small children.

Distance: 5 miles approx.

Map Ref: SE 229 765 Landranger 99

Rating: Walk *** Follies & General Interest ***

"To Hackfall's calm retreats, where nature reigns,

in rural pride transported fancy flies.

Oh! bear me, Goddess to those sylvan plains,

where all around unlaboured beauties rise...."

1822 Guidebook.

Hackfall is a surprise. Its existence is quite unsuspected by anyone passing through the area, and its follies are elusive. The area is quite off the beaten track - Getting your car to Grewelthorpe is by itself a feat of navigation! I came here on a hot Saturday in August and walked for six hours without seeing another human being! At first there is a pleasant village with a duckpond, happy pastures and views over the Vale of Mowbray to the distant Kilburn White Horse, but on entering the woods at Mickley Barras I found myself entering another world, an overgrown, forgotten, haunted world. A place left alone with its memories.

Our journey to Hackfall starts from Grewelthorpe village pond, following the road towards Ripon. A short distance on turn left, (footpath signed 'To Mickley') passing through a gate to follow a grassy track between hedges. Pass through another gate and continue onwards, ignoring the waymarked lane which joins on the left. Beyond a ruin (on the right), the lane ends at a gate by a holly tree. Pass over stile (on right) and follow the hedge round to a second waymarked stile in the field corner. Entering the field, bear slightly to the right, (following the same line of travel) and cross to the next stile, 70 yds up from the bottom right hand corner of the field. Continue in the same direction to the next stile (Waymarked) then across the next field to a post stile, which enters (at the time of writing) a field of sugar beet. Head towards trees, to the right of which will be found a stile and a gate. Continue onwards to the next stile passing Bush Farm on the right, and then after passing a solitary tree at the top of a slope descend steeply down to a waymarked gate which leads into woodlands.

Proceed into the woods, ignoring a descending path on the right, and follow an overgrown path left around the hillside until it joins a rather more well used path coming in from the right. This path leads towards Hackfall Woods.

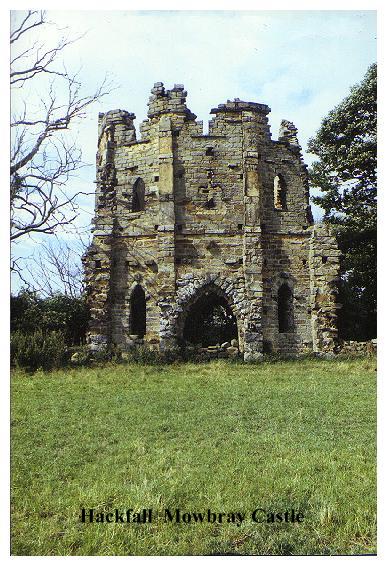

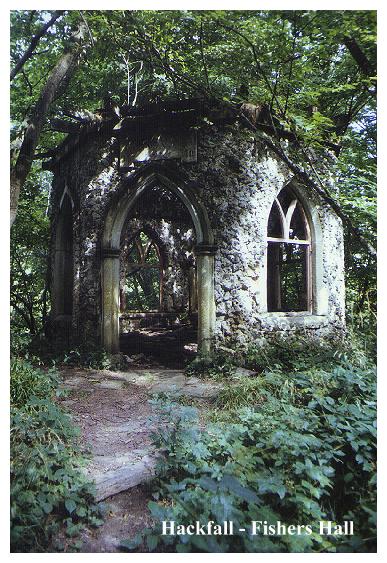

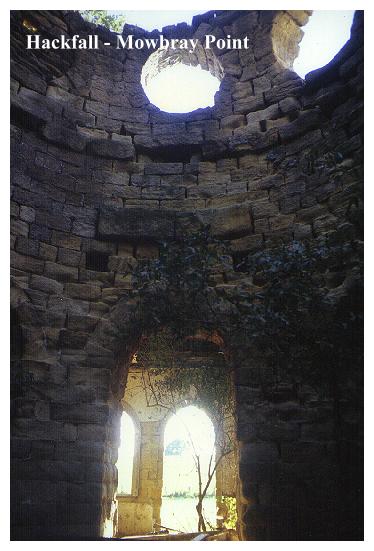

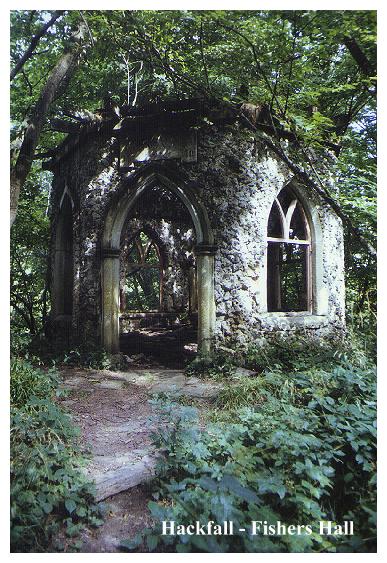

Hackfall is a place of memories. The first echo of them appears, when in the midst of dense woodland, we discover overgrown steps passing up through the crags. At Mowbray Castle the echoes resonate still louder, but it is not until we stand in the midst of the ruined octagonal pavilion of Fisher's Hall, looking at the glinting fragments of glass and shells in the walls that something sad and long vanished crowds in upon your fleeting human prescence and pleads with you to share its story.

The story begins with a tablet over the gothick doorway of Fisher's Hall, which bears the inscription 'W. A. 1750' . Give these 'bones' flesh and we see William Aislabie, plans and designs in hand, exploring the woods, pointing excitedly here and there, surrounded by the nodding assent of his gardeners. Aislabie had recently 'discovered' this steep and remote section of the Ure Valley, and for him it was the ideal place to develop into a 'Romantick' garden. The Aislabies were gardeners and 'folly builders' extraordinaire. William's father, John, had created the beautiful gardens at Studley Royal, and the young William, rightly recognising them to be a masterpiece, had decided, rather than disturb his father's work, to develop his ideas and interests elsewhere. Searching for a suitable place he had discovered Hackfall, and his prayers had been answered.

Work began at Hackfall in 1750 and the end result of all the labour was the first (and possibly the finest) 'Romantick' garden in all England. The 'Hanging Woods',sheer cliffs and turbulent river more than fulfilled the fashionable 18th century whimsy for romantick 'arcadian' landscapes filled with nymphs and satyrs. Where today is 'The Fountain Plain' based on designs from Langley's New Principles of Gardening (1728)? Once, in the midst of a now stagnant pond, a fountain threw water to a great height; and nearby, a 'cascade' fell over 40 feet by a grotto and a rustic temple made from great boulders. The Hackfall Gardens were a wonder, and people came from miles around to see them, including such famous 18th century travellers as Arthur Young and William Gilpin.

The 19th century too viewed Hackfall with wonder. In Victorian times it was owned by Lord Ripon, and a broken obelisk (if you can find it) dates from this period. Hackfall was a pleasant day's excursion for those taking the waters in Harrogate, and in Thorpe's Illustrated Guide to Harrogate of 1886 regular day trips to the 'Hackfall Gardens' are advertised. Even at the turn of the 20th century Hackfall was a favourite resort for 'charabanc trips', would-be- tourists paying a small fee for access to the grounds and gardens. The 1930's however, saw the gardens in decay, and today, apart from the half hidden ruins of the follies, there is virtually no trace of their former glory. The wheel has turned full circle, and now Hackfall is in much the same condition as it must have been on that day in 1750 when William Aislabie first discovered the place. The woods, the rocks and the river remain, a stern example of how quickly nature can erase the traces of man and his works, and only the crumbling follies in their midst, left alone with their memories, offer any hint of the days when this forsaken place was one of Yorkshire's chiefest resorts, the Victorian equivalent of nearby Lightwater Valley. Maybe that place too, symptomatic of the 80's craze for 'leisure parks', will one day meet a fate similar to its vanished forerunner, for unlike man, nature is not subject to the dictates of contemporary fashion, and will always, in the end cleanse the landscape of man's traces.

Perhaps in winter, the traces of Hackfall's former glories are easier to find, but this is not so in summer when the vegetation chokes everything, and creates an atmosphere of green claustrophobia. The woods seem full of sounds, none of them human. By the rapids of the Ure we might well be in the great forests of the untamed American wilderness!

The walk in this book visits Hackfall's three major follies. There is more, but to get a comprehensive picture of what Hackfall must have been like would take a number of visits. The routes from the village to the woods are all on public rights-of-way, but the paths around Hackfall itself are of less certain legality, and arduous to follow in parts.They are, for the most part, marked by purple paint spots on the trees, which does at least imply that it is intended to be some sort of a nature trail.

Entering Hackfall Woods directions are as follows:- when the path starts to descend towards the River Ure, look for a small (not obvious) path which leads up through crags via a series of stone steps. The path leads precariously around the top of the crags, passing above a magnificent deep cleft on the right. After bearing slightly left to cross a small stream at the top of the wood, continue around the hillside until Mowbray Castle appears on the left.

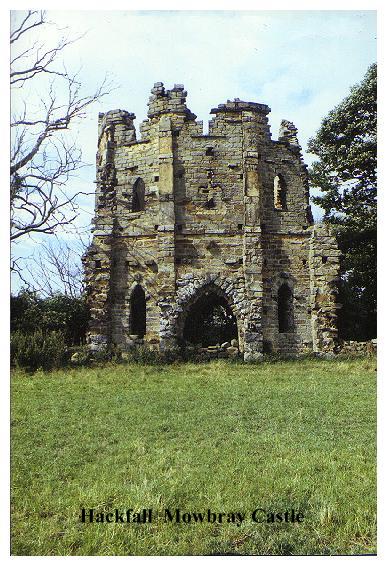

Perched on the crags which form the natural boundaries of the estate, Mowbray Castle towers over woods and river. The view of it from across the valley was painted by Turner in 1816.The 'Castle' is basically a sham ruined 'shell keep' faintly reminiscent of the rather more genuine Multangular Tower in York. The detail is excellent. Even inside we are led to believe that we are looking at the ruin of what was once a floored and roofed building! This of course is quite untrue, for Mowbray Castle was built as a ruin! Aislabie named his castle after the De Mowbrays, feudal knights who once held vast estates and forests in the area. Aislabie's choice of name was therefore not only apt and 'romantick' but was also no doubt intended to lend a touch of authenticity to his spurious and whimsical creation.

From Mowbray Castle continue onwards, (following purple marks on trees!) until the top of the ravine is reached. Resisting the highly visible temptations of the Hackfall Inn, which can be seen over the fields, turn right, cross the stream and then follow the path down the far side of the ravine. After a short ascent to join another path, the path leads down towards the river. Bear right by a fallen tree to emerge at the ruined pavilion of Fisher's Hall which stands forlornly on a knoll above the river Ure.

Fisher's Hall was not built as a ruin. Neglect and vandalism have given it its present appearance. Once upon a time this octagonal lancet windowed pavilion was a grotto room, its walls lined with coloured glass and shells.(A good example of what it must have been like can be seen in the 'Shell Room' in the gatehouse of Skipton Castle.) Fisher's Hall was named after John Aislabie's chief gardener, who, up to his death in 1743 also worked for the son William. Fisher's Hall was not sited here by accident. Below, where the River Ure rushes beneath steep crags and overhanging trees ,the gorge is at its most beautiful.

From Fisher's Hall descend steps to the riverside path and turn left. Soon a sandy beach appears on the right with the remains of campfires. Beyond it a path ascends through woods up Limehouse Hill to meet wall with a coniferous plantation beyond. Bear left, following wall up to a gate at the edge of the wood. From here an indistinct path leads up pastures (wall, fence and ditch on right), to another gate, and another pasture, beyond which lies the road.

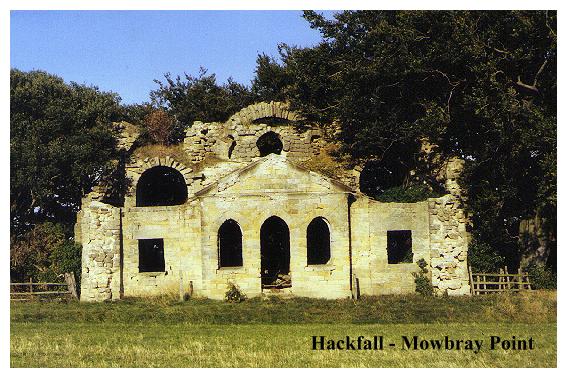

In the final pasture before entering the road a track (not a right of way) leads off left to a gate beyond which the edge of the wood may be followed in order to inspect the magnificent folly of Mowbray Point. (If you do not wish to trespass the folly may be seen distantly from the top of Horsepasture Hill).

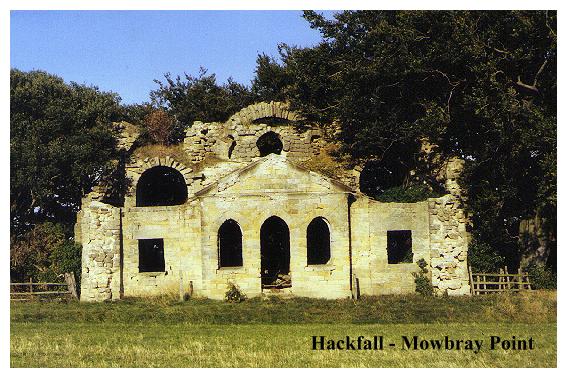

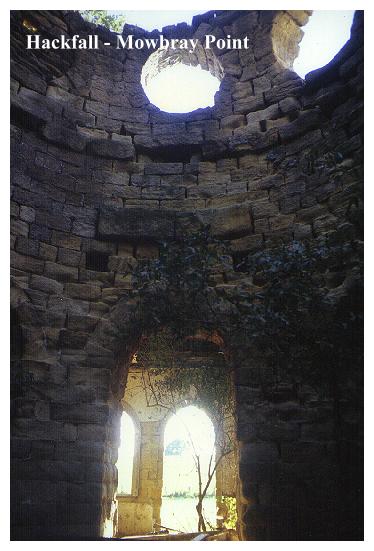

Mowbray Point is in a sad state. Its rafters have collapsed, and its wall niches and ornate plasterwork are shattered beyond repair. Enough remains however, to give you some idea of the interior, and the outside walls are still in their original, (contrivedly ruined) condition. Mowbray Point was built as a banqueting house, and it was here that the victorian tourists would stop to take tea, and no doubt have a rest after the arduous climb up from the river.

It is a two faced building. The side facing the fields is simple enough- an elysian Greek facade, so typical of the architecture of the 18th century. It is the other side of the building, the side that looks out over the woods, which is the real eye opener however. It is in fact, a fake 'roman ruin', being essentially dominated by three arches of crumbling sandstone, which are so cleverly executed that they look like they are about to fall on you! 'Unstable', 'precarious', this 'ruin' nevertheless has stood quite happily since the 18th century! It is so typical of its time. It was undoubtedly inspired by those once highly fashionable paintings of Roman ruins which,shrouded in dense vegetation, form romantic backdrops to pastoral scenes. A good example is the well known picture of the Caracalla Baths in Rome, of which Mowbray Point might almost be a miniature version. Perhaps it was inspired by Langley's series of engravings of sham Roman remains. Certainly the more overgrown the folly becomes the more 'romantick' it appears to be!

Entering the road, turn left then right onto a forest track (signed'Swinton Estate,') Follow the track until it turns right, at which point leave it and continue onwards, following a path alongside between wall (left) and plantation. On reaching the wall corner turn right then left through a waymarked wicket gate. Climb up the hill to a fieldgate, (top left). Beyond the gate pass through a stile in the hedge (on left) and after a brief diversion to the triangulation pillar on Horsepasture Hill bear to the right of powerlines to a waymarked stile in the fence.

Continue over next field to another waymarked stile to the right of a powerline post. (90 deg. to the main line of posts) by a wall corner. Cross the next field diagonally to reach theroad at the far corner.

Turn left, and at the bottom of the hill continue to the next junction then uphill to Grewelthorpe, passing the Hackfall Inn en route. Proceed back through the village to the start of the walk.

By the ancient earthworks on the summit of Horsepasture Hill, views stretch over the Vale of Mowbray to the Cleveland Hills. Below, the Ure Valley appears as impenetrable and inscrutable as before. I did not see the 'Alumn Cascade', Kent's Seat, the 'Rustic Temple' or any of those other attractions listed in the faded pages of 19th century guides. I am sure they must be there somewhere,(or at least what is left of them). As I trudged back to Grewelthorpe hot and tired and hoping (forlornly as it turned out) that the Pub might be open, I realised that my walk would be little more than an introduction to this fascinating place. Hackfall is a place you will have to visit again........

NEWSFLASH!! Things are looking up at Hackfall. Money has been raised and the gardens are under restoration (2007). Mowbray Point, so sadly derelict at the time of my original visit, has been restored and made into a holiday home. Bravo!

Click on 'View Map' option for map and information on new developments at Hackfall (2009) which may influence your choice of route!